The future is all around us and our beloved art form, cinema, is rapidly converting to a digital age. There are those, however, that are still hanging on to film that runs through a camera (see, for example, Christopher Nolan’s die-hard celluloid advocate cinematographer Wally Pfister, who made his directorial debut – on film – with Transcendence), and theirs is obviously a massively important heritage. A full history of different film formats would take a multi-volume book series, but here is a whistle-stop tour of some of film’s key moments, beginning with Thomas Edison and the Lumière brothers, and leading to Tony Scott and James Cameron.

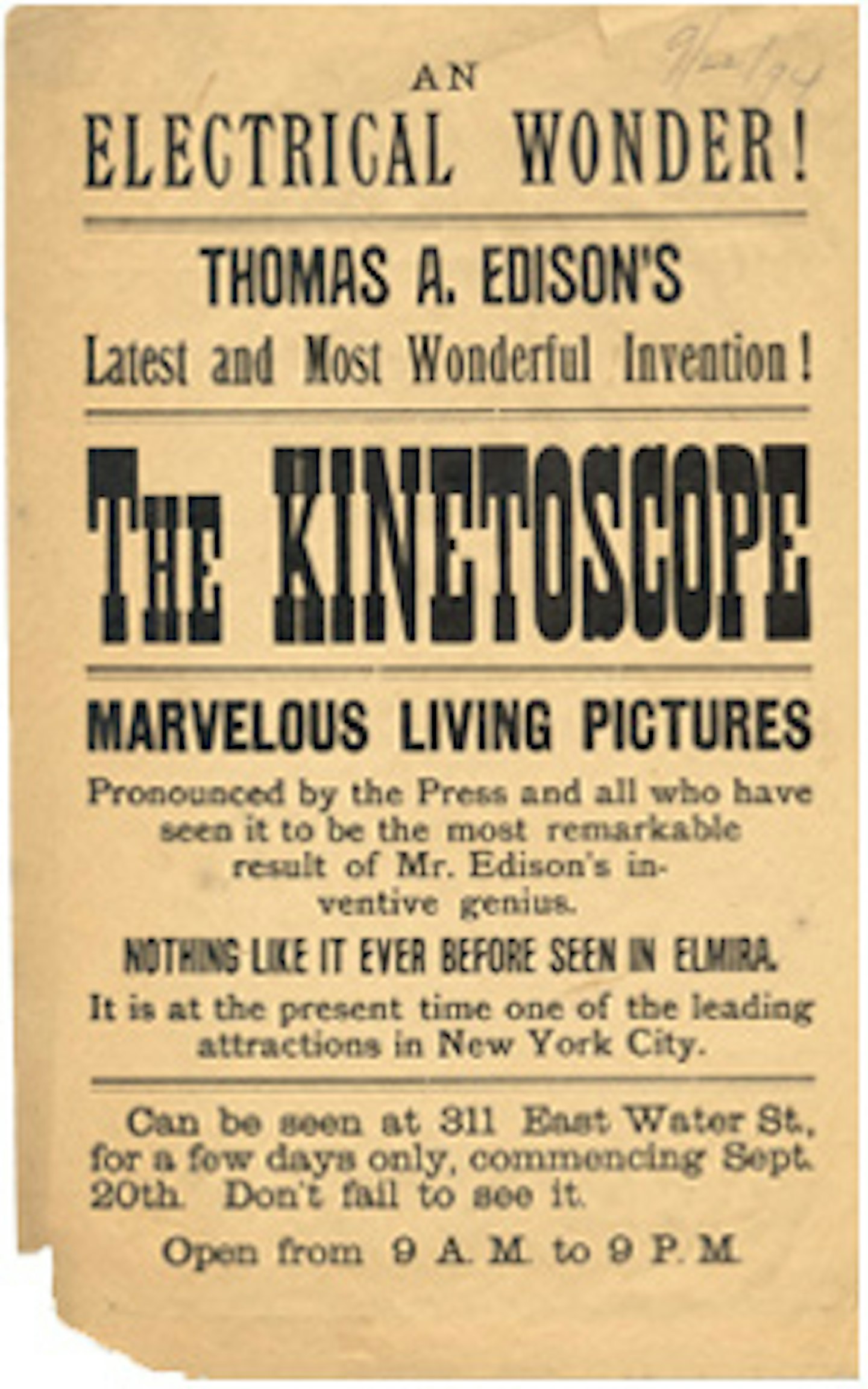

1. Kinetoscope

Year Introduced: 1894

Background: Let’s start at the very beginning, as someone once sang. The very first system for filming and projecting moving images was Étienne-Jules Marey’s chronophotographic gun in 1882, capable of filming 12 frames per second and initially used for his studies in natural history. His pioneering work was followed a few years later by Louis Le Prince’s 16-lens affair (the lenses triggered one after the other to create a frame each) developed and patented in 1886. He followed it with a single lens version in 1888.

The Kinetoscope was initially a single-viewer device that enabled film to be viewed via a peephole. Faced with competition from the much cheaper Mutoscope system, however – those end-of-the-pier, What-The-Butler-Saw, crank-handle devices that were basically flick-books – Edison and his staff began looking to Kinetoscopes that could project an image onto a screen. The Projecting Kinetoscope – advertised for home use – made its debut in 1912.

Key Films: Some of the world’s first films were the Monkeyshines series (blurry figure in white, waving), Dickson Greeting (Edison scientist William Dickson playing with his hat for three seconds) and Newark Athlete (ten seconds of club-swinging). These were tests not designed for public consumption, however. The first Kinetoscope film shown publicly was Dickson’s Blacksmith Scene (1893), which runs for 34 seconds and is also the earliest known example of actors performing roles for the camera.

Pub Trivia: The first film ever to be copyrighted in America was Edison Kinetoscopic Record Of A Sneeze, in 1894 (see below). It’s a five second ‘documentary’ of Edison’s assistant, Fred Ott, taking a pinch of snuff.

Fate: Sound put paid to the Kinetoscope. While Edison did create the Kinetophone, which synchronised the screen image to a record, technicians and exhibitors struggled to use it, and amplification was a problem. It was abandoned in 1914.

2. Cinematograph

Year introduced: 1895

Meanwhile in France, Auguste and Louis Lumière were at work on their own film camera, which doubled as a projector and developer. Their agenda was a machine that improved on Edison’s Kinetoscope, with sharper images and better illumination. They also beat Edison to the projection concept, forgoing the tiresome business of having films that were only viewable by one person through a viewfinder. Its images were more stable, with the film held in place by perforations at the edge of the film strip, and it also had a cooling system to stop the film overheating and catching fire.

The first officially recorded use of the machine was at a private screening in March, 1895. Six months later, the first public unveiling took place, at L’Eden, the world’s first actual cinema, in south-east France. Crucially, however, the Cinematograph, unlike the Kinetoscope, didn’t need a fixed venue. The machine was still operated by a hand crank – as opposed to Edison’s newfangled electricity – but it was portable, meaning it could be set up for exhibition wherever demand took it. The Lumière brothers traveled as far afield as China and India with the invention, as well as to America, where it was a popular attraction in vaudeville theatres and five-cent nickelodeons, making film accessible to even the poorest audiences.

Key Films: The Lumière brothers’ first film and their first to be publicly screened was Workers Leaving The Lumière Factory in Lyon, in 1895. The 46-second documentary shows, er, workers leaving the Lumière factory in Lyon. There were actually three different versions filmed at different times, with variations in dress and the number of horses pulling a carriage (except in the one that has no horses at all). There was also the famous Arrival Of A Train At La Ciotat (1896) (see below), which had early viewers diving out of the way of the screen.

Pub Trivia: The first Indian news film was made with the Cinematograph in 1901. It showed an Indian student returning home from Cambridge University.

Fate: The brothers viewed film as a novelty gimmick with no future. Abandoning their technology and refusing to sell it to others (much to the disappointment of A Trip To The Moon filmmaker Georges Méliès), they turned their attention instead to colour still photography.

3. Fox Movietone

Year Introduced: 1927

**Background: **After 15 years of silent film and dozens of format and technological iterations, the race was on to come up with the first system to attach sound to an image. Warner Bros. worked on the Vitaphone system while RCA developed Photophone and Fox had Movietone. Vitaphone used a 33rpm record synchronised with the film (the process used for The Jazz Singer), while Photophone and Movietone used a more sophisticated “optical sound-on-film” process, actually adding the soundtrack to the film strip. Photophone was used to attach sound to some prints of William Wellman’s Wings, while Movietone was the system F. W. Murnau chose for Sunrise. The silent masterpiece was officially the first professionally produced feature film with an optical soundtrack.

Movietone came courtesy of Theodore Case, and actually evolved out of another system, Phonofilm, which Lee de Forest had been developing since 1919. Case and De Forest collaborated for a while until Case became annoyed with de Forest claiming all the credit for his work. He went his separate way, and Movietone was born. With some bumps along the road, it was eventually cracked as a single-system camera, with image and sound recorded on the same negative. Running at 24 frames per second – as did Vitaphone – it helped establish the standard speed for sound films that was used almost exclusively from then on.

Key Films: Murnau’s aforementioned Sunrise (below) was the first film to have sound actually printed on the film. It isn’t a “talkie”, however, since the soundtrack is music and ambient noises, with only sporadic instances of background voices (in the sequence at around the 45 minute mark, for example). Fox used the Movietone system for all its features between 1927 and 1931, and continued to use it for newsreels until 1939 because the system was so portable. The brand name Movietone News continued well into the ‘60s.

Pub Trivia: Movietone films will still run on modern film projectors.

Fate: Movietone was superseded by a cheaper and more sophisticated system developed by Western Electric in 1931.

4. Cinerama

Year Introduced: 1952

Background: Moving past its novelty and nascent forms, cinema’s next agenda was spectacle. The square-frame Academy ratio (1.37) was agreed as a unifying industry standard in 1932, and all studio films for the next two decades were made in that format. But then came the Widescreen revolution in 1952, first arriving in the form of Cinerama.

A portmanteau of “cinema” and “panorama”, Cinerama evolved from Vitarama, a gunnery training system developed by mechanics and photography genius Fred Waller. Its commercial version, perfect for showing massive vistas on huge, curved screens, was mostly used for travelogues, many of which were conceived and narrated by the adventurous Lowell Thomas. It was only employed on two narrative feature films: How The West Was Won and The Wonderful World Of The Brothers Grimm (both in 1962).

The system used three cameras shooting three separate square images, which were seamlessly projected together onto the screen from three separate projectors to form a picture three times as wide as it was high (a process not dissimilar to that used by Abel Gance for the climax of Napoleon in 1927). It was prohibitively expensive, since it required theatres to be built or adapted to house the giant screen and extra projecting equipment.

Key Films: Cinerama’s first great success was This Is Cinerama in 1952. Audiences were taken on a panoramic journey through footage of a rollercoaster, Niagara Falls, water skiers and the Edinburgh Tattoo. Similar travelogue-type documentaries followed, such as The Seven Wonders Of The World (1956, self explanatory) and Windjammer (1958, about the epic voyage of a Norwegian sail training ship). How The West Was Won and The Wonderful World Of The Brothers Grimm were its only dramatic features.

Pub Trivia: The Cinerama Dome on Hollywood’s Sunset Boulevard still exists as a prestigious theatre with a massive screen. It was declared a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument in 1998.

Fate: Cinerama was both too expensive and too unwieldy for making narrative feature films. It couldn’t be used for anything closer than a mid-shot, and directors complained that actors couldn’t even perform to one another’s eyelines because of the way shots had to be composed for the three cameras. It was replaced for production by single-camera systems like Ultra Panavision 70 and Super Technirama 70 (used for things like 2001: A Space Odyssey and Ice Station Zebra), and these films were then optically converted for Cinerama projection so that the brand name could live on.

5. Cinemascope

**Year Introduced: **1953

Background: 'Scope, as it was known to studio execs, was Cinerama’s replacement. It was introduced by 20th Century Fox as a less unwieldy way to make its epics just that bit more, well, epic. Rather than use three cameras and three projectors, the ingenious solution was to use anamorphic lenses. On a camera, these lenses distort the image so that it’s recorded onto a standard “square” Academy aspect film stock looking squished (compressed). Then when projected back through the right lens, the image displays correctly on the wide screen (dilated).

Fox was unable to patent the system because the technique was not a new one. The French inventor Henri Chrétien had experimented with his Hypergonar lenses in the 1920s, for a process he called Anamorphoscope, and Hans Holbein’s painting "The Ambassadors" (recently pissed on by Dylan Moran in Calvary) contained an anamorphic image of a skull as early as 1533. Other studios then, were free to figure out their own versions, leading to Paramount’s VistaVision, RKO’s Superscope, and Technicolor’s Technirama. Only Warner Bros. decided to stump up and license CinemaScope from Fox, rather than pursuing its own abandoned Warnerscope process. Despite so much competition, 'Scope remains the widely-used term for any widescreen image among filmmakers and projectionists.

Key Films: Richard Burton’s The Robe – the Spartacus-meets-Passion-Of-The-Christ of its day – launched the new format promising "the modern miracle you see without glasses" (above). That sly dig at the 3D peddlers of the time was splashed across advertising. Disney also had great success with the format, with the live-action 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea, and CinemaScope’s first animation, Lady And The Tramp.

Pub Trivia: Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Mépris had Fritz Lang disparaging the format as fit only for "snakes and funerals".

Fate: Died out by 1958 as filmmakers and studios adopted the cheaper and technically superior Panavision.

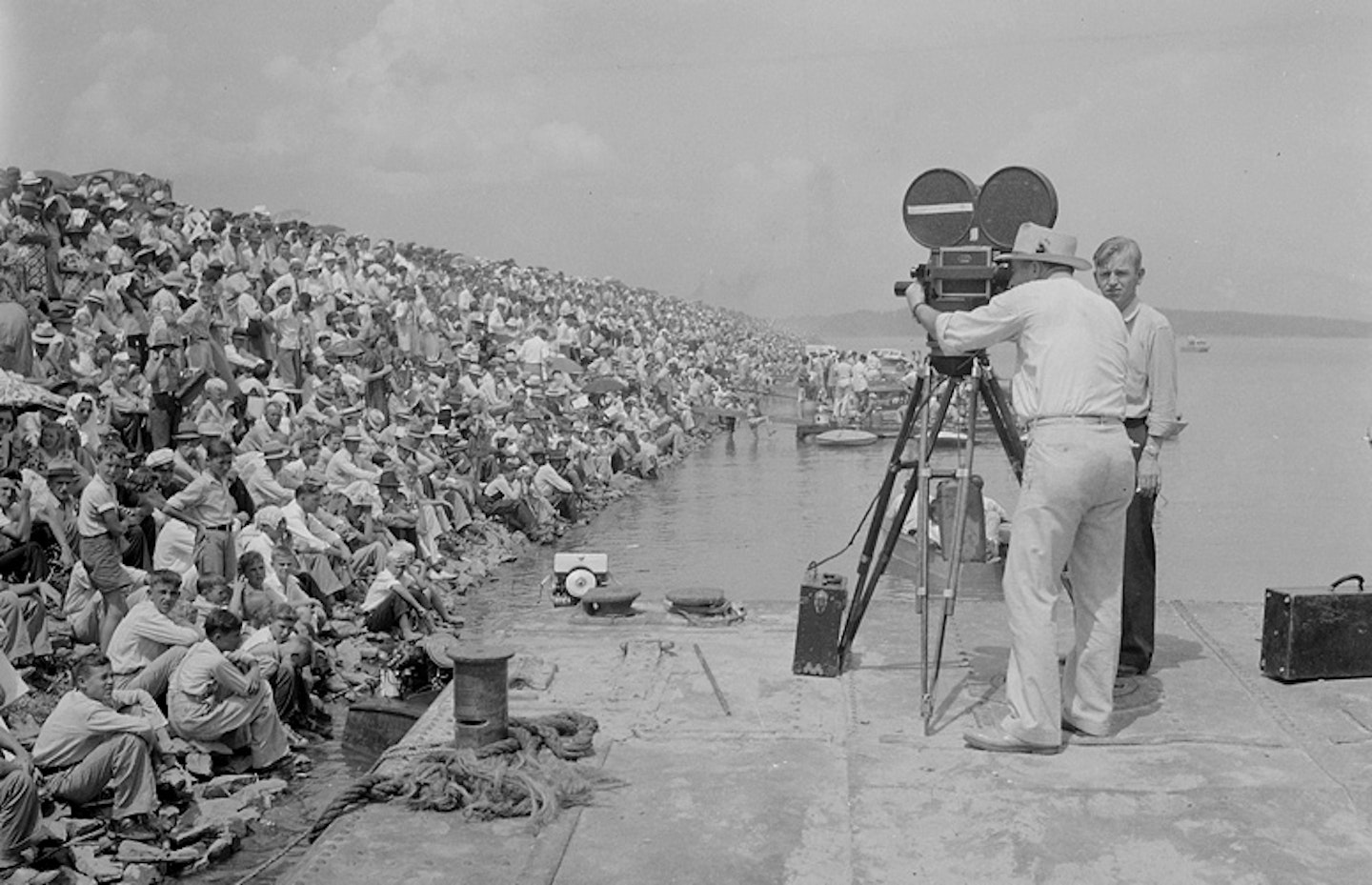

6. Todd-Ao

Year Introduced: 1955

Background: The one-upmanship continued, with the next idea to improve both the resolution and sound of widescreen film. Experiments in 70mm film – Paul Thomas Anderson's pick for The Master – dated back to Fox’s ‘Grandeur’ system of the 1920s and earlier, but were revived in the wake of Cinerama and CinemaScope. Producer Mike Todd, one of Cinerama’s founders, gave his name to the Todd-AO process. Feeling CinemaScope didn’t quite cut the cine-mustard, he wanted to recreate the full three-camera/projector Cinerama experience "out of one hole".

Todd-AO was initially intended for projection on a huge, deeply-curved screen like Cinerama. Ultimately, practical considerations kiboshed this idea, although a ‘roadshow’ distribution format, in which films were booked into Cinerama-capable theatres for extended runs, was common. It also started out projecting faster than regular film, at 30fps instead of 24fps, but again, this fell by the wayside early on, since it made the film so hot that it had to be cooled as it travelled through the projector. Eschewing anamorphic lenses, Todd-AO went spherical.

Aside from scale and resolution, Todd-AO was notable for its sound clarity. Like CinemaScope, its soundtracks were strips of magnetic oxide on the film, but there were six audio channels compared to CinemaScope’s four, five of which led to speakers behind the screen, with the sixth creating a surround-sound effect through speakers on the auditorium walls.

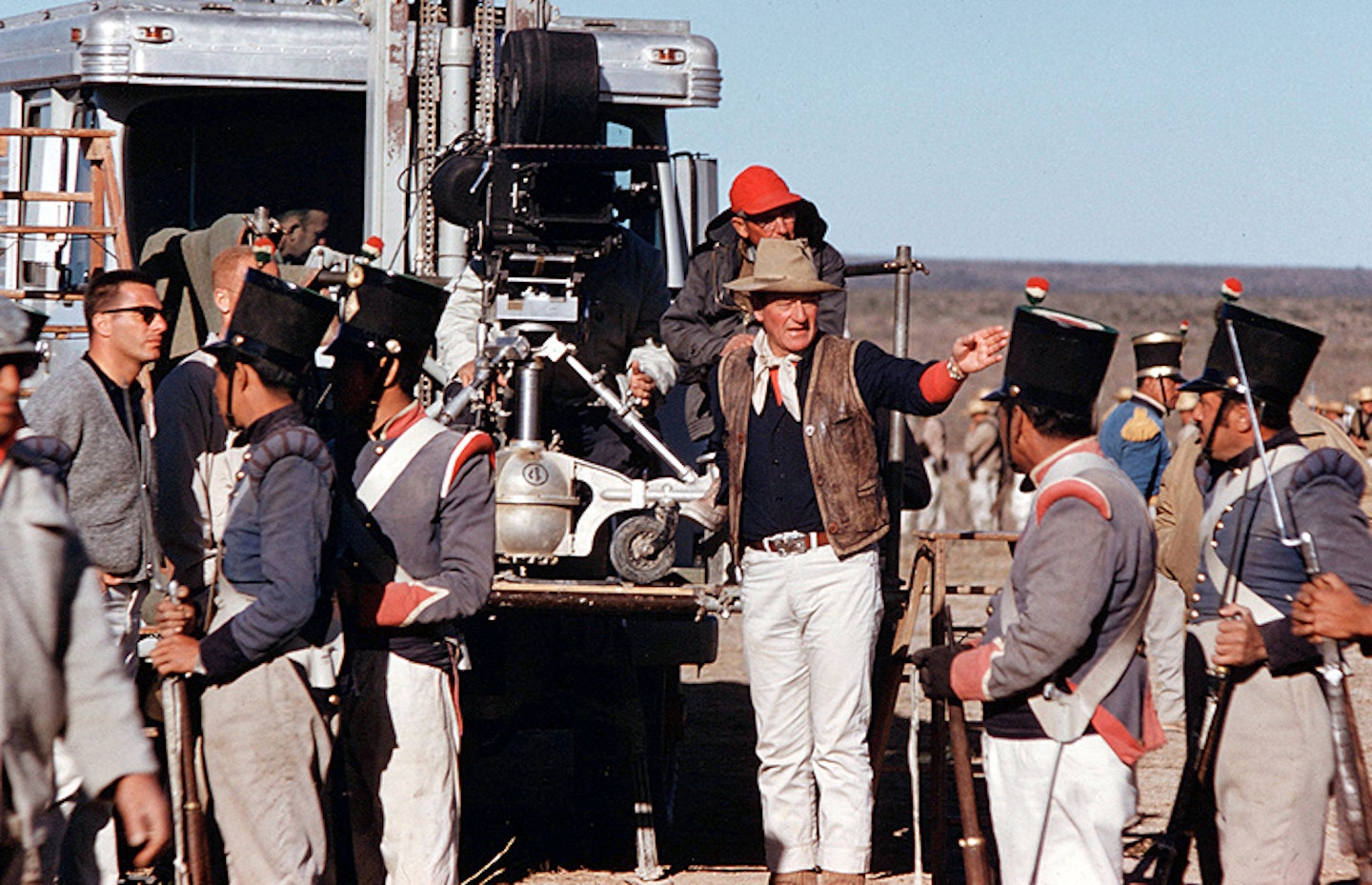

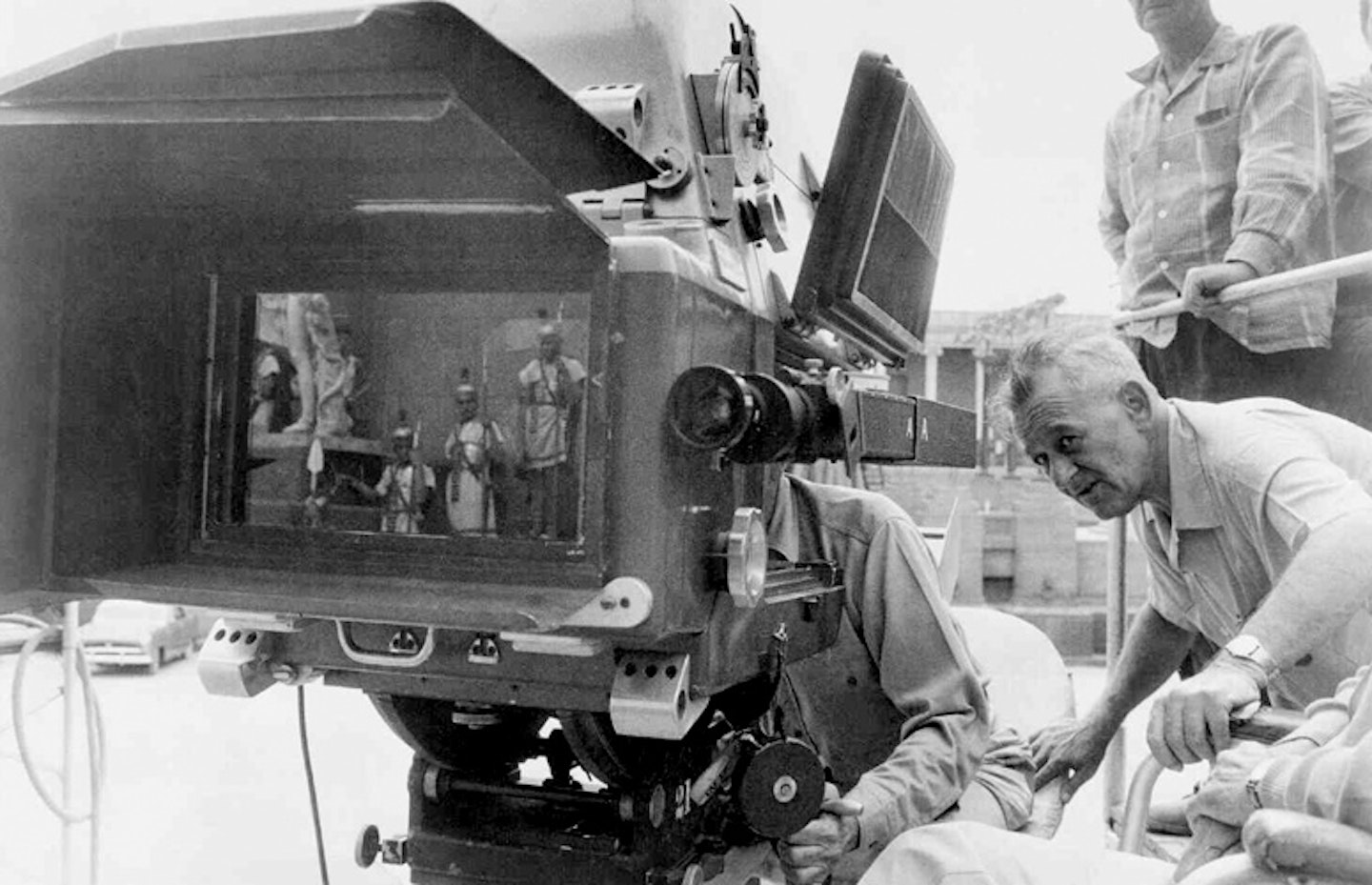

Key Films: With its mega sound, Todd-AO was great for musicals. Rodgers and Hammerstein were particularly enamoured, approving it for Oklahoma! (1955), South Pacific (1958) and The Sound Of Music (1965). It was also used for Can-Can (1960), Doctor Dolittle (1967) and Hello, Dolly! (1969), and for non-musical spectacles like John Wayne’s The Alamo (1960) (pictured above), Airport and Patton (both 1970).

Pub Trivia: Conquest Of The Planet Of The Apes (1972) was filmed in a short-lived 35mm version of Todd-AO. All the other original Apes films used Panavision.

Fate: The business was stagnating and the system little-used by the 1980s, and the company was folded up and sold off.

7. Techniscope

Year Introduced: 1960

Background: Techniscope was a cheap widescreen process developed by the Italian arm of the Technicolor corporation. Despite lower grade results than its forefathers like CinemaScope, it became ubiquitous, and, having been introduced in 1963, it was still in use in 1980.

Its main innovation was to halve the amount of stock needed for a production, by having each frame take up only two perforations on a film strip (most systems use four). This meant combining the techniques of using spherical and anamorphic lenses: spherical to stretch the image vertically back up to normal size; then anamorphic to stretch it horizontally again for the correct widescreen aspect ratio.

Unsurprisingly, given its country of origin, Techniscope was almost the sole system for shooting and projecting spaghetti Westerns, and was also popular for horror. In the US it was also used for low-budget B movies. Paramount and Universal, however, with their eyes on their bottom line, used it extensively for a time during the ‘60s.

Key Films: Sergio Leone shot the Dollars trilogy, A Fistful Of Dynamite and Once Upon A Time In The West (above) with Techniscope. The system was also used for The Ipcress File; Amicus’ 1960s Dr Who films; George Lucas’s THX 1138 and American Graffiti; Monte Hellman's beatnik road classic Two-Lane Blacktop; Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain; and various Dario Argento and Lucio Fulci horrors.

Pub Trivia: Techniscope has had a revival of sorts in recent years, with cameos in Silver Linings Playbook and Argo.

Fate: Techniscope was a production-only format that incurred conversion costs in its journey to exhibition, increasingly so as technology changed and orders for prints declined in the ‘70s. So while it started out as a cheaper option, conversion costs gradually eroded those savings, and it died out.

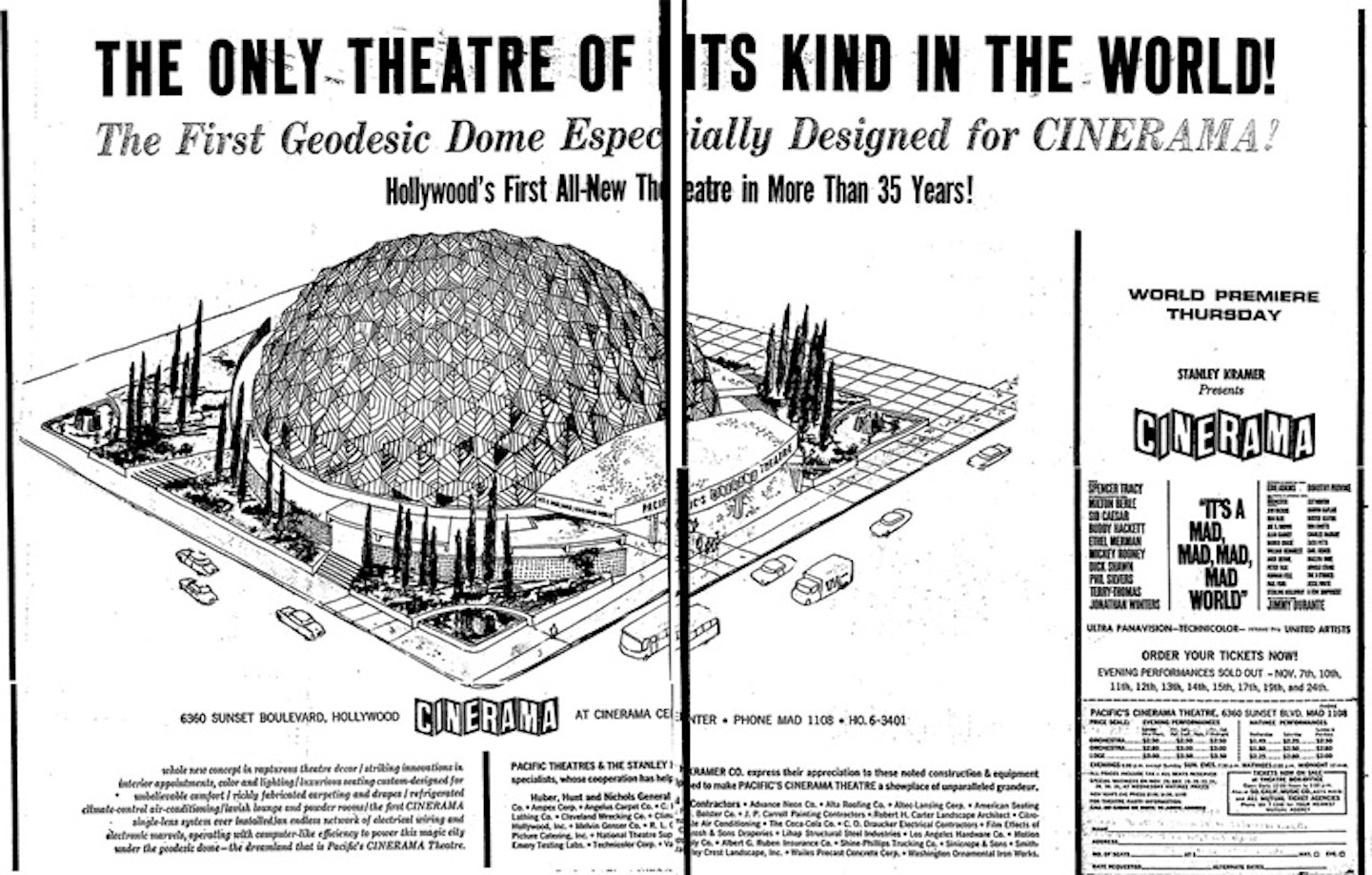

8. Ultra Panavision 70

Year Introduced: 1962

Background: Panavision is both a manufacturing company and a film system in itself. Many studios employed Panavision lenses and equipment from the company’s inception in 1953, but it was a partnership with MGM that led to the so-called Camera 65 process in 1957, renamed Ultra Panavision in 1960.

Cinemascope, due to its compatibility with normal 35mm projectors, had established itself quickly, but had problems with excessive grain on the image, as well as other distortions. MGM, like Warners, decided to license CinemaScope from Fox rather than build its own version from scratch. Its partnership with Panavision was brokered to build on and improve the Fox system.

Ultra Panavision had some key differences to the superficially similar Todd-AO. It used the industry standard 24fps and was designed to be projected onto a flat screen rather than Todd and Cinerama’s concave behemoth. But its picture was even wider, with its cameras compressing the filmed image anamorphically 1.25 times, creating a screen ratio 2.76 times as wide as it was high (2.76:1). Todd-AO’s lenses could only manage 2.20:1.

Key Films: Obviously bigness remained the point, so Ultra Panavision gave us the chariot-smashing of Ben-Hur (which stayed in theatres for a year) and the Brando-sailing of Mutiny On The Bounty. Several films shot in this way – It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World; The Fall Of The Roman Empire; Khartoum – were also blown up to be projected for Cinerama.

Pub Trivia: Ultra Panavision 70 was originally called MGM Camera 65. The anomalous 5mm is where the sound strip goes. MGM and Panavision shared an Oscar in 1960 for inventing the system.

Fate: Widescreen films existed in the first place partly to reward audiences for foregoing the stay-at-home comforts of television. But it was a relatively short-lived fad, and once the novelty wore off, audiences declined and studios largely stopped bothering with spectacle formats. Ironically, part of the problem was that widescreen films transferred very badly to square TVs.

9. IMAX

**Year Introduced: **1970

**Background: **Like Ultra Panavision 70, IMAX sprang from a desire to recreate the awe-inspiring spectacle of Cinerama, but from a single source. It’s raison d’être was to create a single massive image to deliver a greater impact than multiple smaller ones. IMAX (short for ‘Image Maximum’) was the Canadian, independently-created result of development work by Graeme Ferguson, Roman Kroitor, Robert Kerr and William C. Shaw, and went on to surpass and replace all its predecessors.

Like Cinerama, IMAX proved to be an unwieldy system. Consequently, its initial decades saw it used for geographic and natural history documentary features, in specialist auditoria like science centres, theme parks and planetariums. It uses a 65mm film stock, which runs through a projector horizontally (as opposed to 35mm’s vertical spooling) at a speed of 102.7 metres per minute. It requires three times as much film as normal to replicate the standard 24fps speed, hence the shorter running times of films natively shot in IMAX rather than converted to the format post-production. In order to maximise the space for the image on the film, IMAX uses an entirely separate film strip for its soundtrack, played on a separate machine locked to the picture (in the same way Vitaphone used an accompanying record). The audio switched to a digital format in the 1990s.

Key Films: The 17-minute Tiger Child was the first IMAX film, making its debut at an expo in Osaka in 1970 (the first permanent IMAX installation was unveiled in Ontario in 1971). The format’s technical specs make it difficult to shoot features with – the films we watch in IMAX today are almost all blown up from other formats – but it was used for The Rolling Stones’ 80-minute concert film Live At The Max in 1991 and for Jean-Jacques Annaud’s 50-minute dramatic feature Wings Of Courage in 1995. More recently, Christopher Nolan used IMAX to shoot portions of The Dark Knight and The Dark Knight Rises. On Interstellar he even strapped an IMAX camera to a Learjet.

Pub Trivia: The first feature-length animation released in IMAX was Disney’s Fantasia 2000. It set new box-office records for IMAX grosses, taking over $2m from just 75 theatres worldwide.

Fate: Still going strong.

10. Super 35

Year Introduced: 1982

Proving that good ideas never really go away, Super 35 (originally known as Superscope 235 and also called Super Techniscope) returned to the original frame size used by 35mm silent films. The film has 32 per cent more image area than regular 35mm, because, being a production format only, none of the frame space is used for an audio track. Films shot in Super 35 don’t travel to theatres as Super 35 prints, instead getting a post-production rejig into a more standard format. Spherical rather than anamorphic lenses are used, saving money on both lens rental and film: the lack of wasted frame space in the process allows a normal film magazine to shoot a third more material than standard.

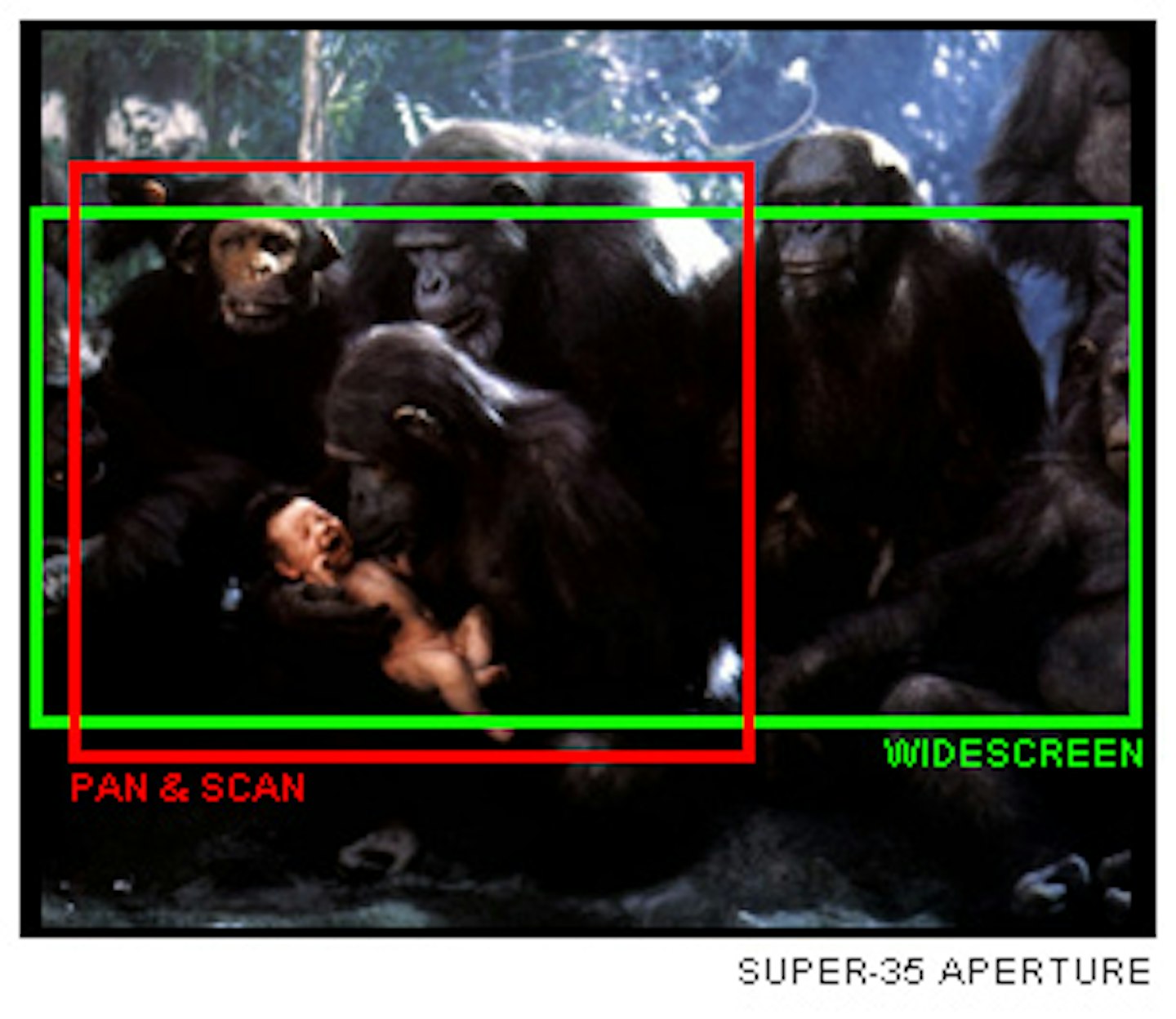

Background: Super 35 has been used to shoot more than a thousand movies, and became a standard production format for music videos and TV shows. It was also useful back in the pre-widescreen-TV days for producing television and video versions of widescreen feature films. Rather than the "pan-and-scan" technique in which films were cropped for the square screen, Super 35 allowed films to be shot at full-frame ratios, with the top and bottom of the image "masked" for the DOP’s intended widescreen composition. The masking was then removed for a square TV image. Back To The Future was a classic example of this, with many people, faced with the widescreen version on VHS for the first time, complaining that it lost screen information in its director-intended ratio, compared to the square-screen video version they'd been used to. It gained nothing at the sides but lost information from the top and bottom; widescreen wasn't wider in that particular instance (and many others), just shorter.

It offers a poorer, grainer image than its predecessors and competitors, but in the days of TV, video and smaller cinema screens, it got away with it.

Key Films: Greystoke (1984) was the first Hollywood film to use the system, and James Cameron was an enthusiastic adopter, first using it on The Abyss (1989). It also made the cockpit shots possible in Tony Scott’s Top Gun (1986) (above), since a 35mm camera would not have fitted in that tiny space with a massive anamorphic lens attached to it.

Pub Trivia: Super 35 was originally called Super Techniscope, and was first used on the British two-tone music documentary Dance Craze.

Fate: While film is increasingly being replaced by digital shooting formats, Super 35 is, relatively speaking, more popular than ever. The cropping required is, ironically, made much easier and less damaging to the image by digital post-production.