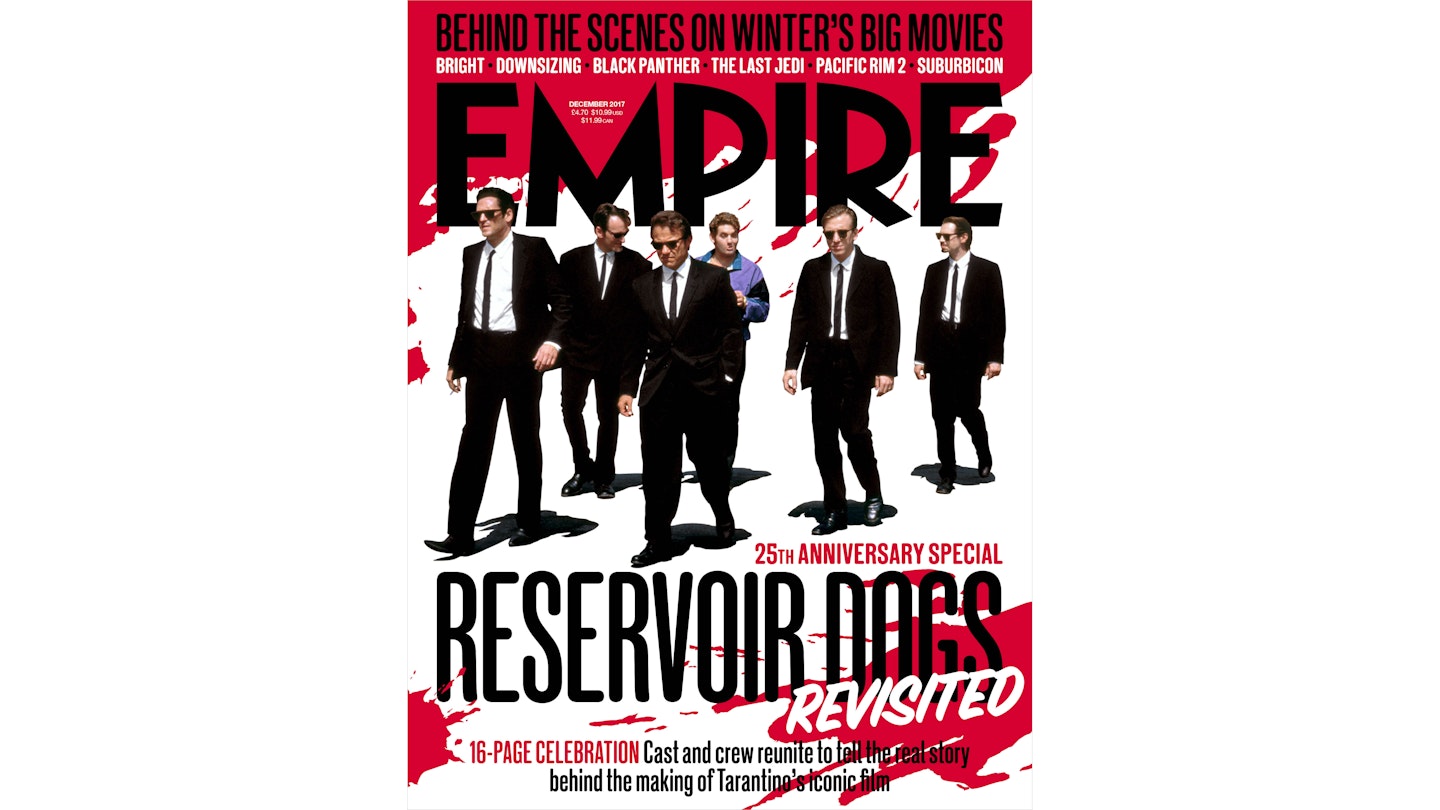

First published in Issue 44 of Empire (Way back in February of 1993) the following article marked the emergence of a little independent movie called Reservoir Dogs. 25 years later, Empire has reunited many of the cast and crew for an exclusive retrospective and that very special issue is on sale right now at all good newsagents. Head out and buy it while stocks last{

It has been hailed as the most original debut for decades. It has been likened to Scorsese at his very best. It is, of course, Reservoir Dogs, and it is currently earning its creator, Quentin Tarantino, major Boy Wonder status around the world. Jeff Dawson meets the director and his stars Tim Roth and Harvey Keitel...

"You know, Madonna liked the movie a lot and wanted to meet me," chuckles Quentin Tarantino. "So I asked her, 'Am I right about the song?' because I really believed that was the subtext. She said, 'No, it's about love, it's about a girl who's been messed over and she finally meets this one man who loves her.' She signed my Erotica album, 'To Quentin. It's not about dick, it's about love. Madonna.'"

Quentin Tarantino is, of course, referring to the classic opening of Reservoir Dogs, his stunning directorial debut, in which Mr. Brown - played by Tarantino himself - expounds to the guys in the diner his somewhat eccentric interpretation of Like A Virgin ("It's about a girl who digs a guy with a big dick"); a scene which swishes back the curtain on a tale of macho bravura in the aftermath of a diamond heist - a high testosterone movie redolent of Kubrick's The Killing or Huston's The Asphalt Jungle made by a young Scorsese - which, translated, means that Tarantino is the hot new Hollywood talent.

Tall, rangy and sporting an unkempt thatch of hair, Quentin Tarantino is not, however, your immediate idea of a "man of the moment". Tucked away in the corner of a Whitehall pub, he is more interested in this, his third pint of draught Guinness, than buying into the Next Big Thing malarkey.

Probably because he wolfed down too many E numbers as a child, Tarantino is extremely animated. He is also eminently likeable, which probably explains how he got away without a dressing down from the world's number one female recording artist, having described her as a "regular fuck machine" in his script. Speaking quickly in a voice not unlike that of Mickey Dolenz and punctuating his enthusiasm - "It's a really incendiary movie, you can't show it to an audience without getting a reaction" - with words like "man" and "cool", he really is rather proud of his creation.

And so he should be. The 29-year-old writer-director has come a long way in the last couple of years. After training as an actor and enduring various false starts on the production side of things (his first job was as an assistant on a Dolph Lundgren video, literally clearing the dog shit out of the car-park so Dolph wouldn't get his trainers dirty) he spent six years killing time in an L.A. video shop until one day, out of pure frustration, he began to hatch a big idea.

I didn't write the part for Harvey because I thought it'd probably be, you know, my uncle Pete..."

"It's a simple fact that I get a kick out of heist films, so I thought I'd write one," begins Tarantino matter-of-factly. "I'd had the idea in my head about a film that doesn't take place during the robbery, but in the rendezvous afterwards. When I worked at the video store we had this one shelf that was like a revolving film festival and every week I would change it - David Carradine week or Nicholas Ray week or swashbuckler movies. And one time I had heist films, like Rififi and Topkapi and The Thomas Crown Affair. I started taking them home and it was in the context of seeing a heist movie every night that I put my head round what a neat genre that would be to redo." The Guinness long forgotten, Tarantino is now in full swing.

"The thing about heist films is they have this built-in suspense mechanism," he babbles, "even with something like Treasure Of The Four Crowns, you know, that crazy 3-D movie, it's like, 'Oh my God, they're getting too close to the beam,' and you get real nervous, so I thought, 'Okay I'm gonna do one of these.' And I thought I'd write one where they all got away, 'cause I hated it - I hated it - where they'd do the robbery and just by some little quirk, fate steps in and fucks 'em over."

Idea firmly implanted, Tarantino scarpered off to the stationery shop and purchased a set of felt-tip pens and a notebook - "You can't write poetry on a computer" - declaring to his gobsmacked mates that these were the tools with which he was going to create a masterpiece and, over the course of three weeks, he duly bashed out a script. Backed by an influx of residual cheques from the repeat fees of an episode of The Golden Girls in which he had played an Elvis impersonator, Tarantino ran his idea by producer chum Lawrence Bender and, armed with $30,000 and a 16mm camera, set about making his movie. "I was gonna be Mr. Pink and he was gonna be Nice Guy Eddie and we were gonna get some friends to play the other parts," he explains. Then, on returning home one evening, Tarantino switched on his answerphone to hear the Brooklyn tones of none other than Mr. Harvey Keitel expressing his deep interest in their little project.

"What happened was that Lawrence was going to an acting class, and his acting teacher's wife knows Harvey," recalls Tarantino. "She gave the script to him and he just called us up three days later and said, 'Look, consider me in. Not only do I want to do it, I want to be one of the producers. I want to help get it made. Whatever I can do, let me know.'" Tarantino beams at the thought of his extraordinary good fortune.

"It was wild, because Harvey had been my favourite actor since I was 16 years old," he blurts. "I'd seen him in Mean Streets and Taxi Driver and stuff. I didn't write the part for Harvey because I thought it'd probably be, you know, my uncle Pete..."

Harvey Keitel, it has to be said, does not engage easily in conversation. Whether it's all part of that deep Method thing or if it's just some game he likes to play is entirely unclear. He may well go home, rip the tab off a beer and regale his kith and kin with hilarious tales of his youth, but that's not the official line. Harvey doesn't like talking about the past; Harvey doesn't like talking about the future; Harvey won't talk about anything the director can't say better. Harvey will only talk about his character, and even then he doesn't give much away. Instead, he fixes you with that intense stare, brow furrowed, as if words alone cannot convey the depth of feeling he has for his craft, tossing out a series of aphorisms - "The analysis of the text is the education of the actor"; "Rehearsal is a journey, let the possibilities happen" - from the armoury of the Method thespian.

Very much back in the frame (Bugsy, Thelma & Louise and the forthcoming Bad Lieutenant) after a lean period in the 80s (Saturn 3 or The Pick-Up Artist, anyone?), Harvey Keitel, still undoubtedly a screen "great", seems to have a Midas touch with first-time directors.

"It seems to have occurred that way," he dismisses modestly. "Yes, there was Scorsese and Alan Rudolph, Ridley Scott, Paul Schrader and now Quentin Tarantino - it just seems to have gone down that way. I'm always searching for an experience, and Quentin came along and provided it with this provocative piece of material."

Quentin Tarantino is rather more succinct about his hero - "He comes in, kicks ass and leaves" - which, in effect, is what Keitel did, jump-starting the project with his own cash, adding to the modest $1.5 million budget.

In movies, everybody has to be so fucking *likeable*. You can write a novel about a perfect bastard, it doesn't mean you don't want to turn the page.

"The thing was, we weren't fully financed when we started casting," explains Tarantino. "We said, 'Look, if we just wait around, nothing's gonna happen.' We were based in L.A., but Harvey said, 'We really owe it to ourselves to get a shot at the New York actors,' and he bought our plane tickets, put us up in a hotel and set aside the weekend for a casting director friend of his to see actors in New York."

And so the casting began, and having eaten his way through Keitel's kitchen, Tarantino emerged with his dream team: Michael Madsen (Susan Sarandon's lover in Thelma), Chris Penn (brother of Sean), Steve Buscemi (a Coen brothers favourite), real-life bank robber Eddie Bunker, septuagenarian Lawrence Tierney (veteran of 1946's Dillinger) and, of course, Britain's own Tim Roth as Mr. Orange.

Roth, like his good friend Gary Oldman, is now seemingly destined to work in the US - "Americans make films about their own country, whatever kind of dishevelled state it's in. They at least do it, whether it's good or bad" - but he is still very much the English Jack The Lad as the sleeve of his t-shirt hitches up to reveal a tattooed forearm bearing the legend P.E.R.I.S.H.

"You get a stack of scripts sent to you and this was the first refreshing thing I'd read that had real energy and something new about it," explains Roth. "My agent had put a little note on the front saying 'Look at Orange.' I didn't even know what that meant..."

Roth, though, was thrilled at the prospect of working with Keitel - "I don't know quite what goes on in his head, but there's lots of thinking" - and began preparing for his part, which involved writhing around in a pool of blood for rather a long time - "That was very sticky. It's a syrup which dries under the lights, so you're actually stuck to the floor at some points." He also had to sort out that all-important L.A. accent, which resulted in a special arrangement whereby his irritatingly ever-present dialect coach plays the victim of one of the film's shootings.

"We were very pleased about that," he chortles. "They drive you crazy."

What fascinated Roth more than anything, though, was the structure of Tarantino's script, as the main scene in the warehouse, set in Real Time, is inter-chopped with a novelistic method of storytelling, "chapters" of information thrown at the audience with no regard for chronology.

Tarantino, in fact, is obsessed with this aspect of his film, which certainly shuffles the viewer's traditional sense of perspective.

"I actually think that if movies were to follow closer the rules for novels, they would benefit," he enthuses. "In the transition from novels to movies, one of the first things that goes is the structure. Chronological order isn't the only way you can tell a story. Novels go back and forth all the time. A novel thinks nothing of starting in the middle of the story." Tarantino, it is clear, has got his teeth sunk in.

"And in movies, everybody has to be so fucking likeable," he barks. "You can write a novel about a perfect bastard, it doesn't mean you don't want to turn the page. I like deciding what I'm gonna reveal and when I'm gonna reveal it, I think a certain suspense comes from that. I don't know if you're confused in Reservoir Dogs, but you're curious about what the fuck's going on."

Tarantino has been just as obsessive with the visual appearance of his movie. Ultra-hip, his Reservoir Dogs - "It's just a perfect title for those guys, they are Reservoir Dogs, whatever the hell that means" - drip with style as they drive around in big sedans and sport the same classic outfit, a sort of 60s Blues Brothers affair which gives the film a timeless quality.

"You can't put a guy in a black suit without him looking a little cooler than he already looks," declares Tarantino. "It's a stylistic stroke but it also has a foot in reality. Robbers often adopt a uniform - whether it be black suits or Raiders jackets - so when the cops show and ask witnesses what they looked like, they say, 'How do I know, they looked like a bunch of black suits.' They all blend in."

Indeed, this disorientation is cleverly compounded by the use of cultural reference points in the movie - old TV shows like Get Christie Love and Baretta - with Tarantino masterfully deploying an oldies soundtrack in the form a radio show, K. Billy's Super Sounds Of The 70s, and the deadpan voice of its DJ, comedian Steven Wright.

My mum really liked Reservoir Dogs, she just said, 'All those guys in their black suits with that music, walking together, they just look so male.'

"I love the use of music in movies," enthuses Tarantino, fired up again. "You know Ride Of The Valkyries has been around for a hundred years, but I defy anyone not to think of Apocalypse Now when they hear that piece of music. And when I hear the opening strands of The Ronettes' Be My Baby I see Harvey Keitel's head hit the pillow in Mean Streets. In L.A. you have a lot of oldie stations and they have special weekends - a Motown weekend, a Beatles weekend - so I came up with the idea of a Super 70s weekend. I didn't want to go for the serious stuff - Led Zeppelin or Marvin Gaye - I wanted to go for the super-sugary 70s bubblegum sound. One, because some people are annoyed by it and, two, because I grew up with it. The sugariness of it, the catchiness of it, really lightens up a rude, rough movie."

In fact, not since the use of Singin' In The Rain in A Clockwork Orange has a piece of music been put to such disturbing effect, as a piece of brutal torture is committed to the incongruous strains of Stealer's Wheel's harmless little ditty, Stuck In The Middle With You.

"That scene would not be as disturbing without that song because you hear that guitar strain, you get into it, you're tapping your toe and you're enjoying Michael Madsen doing his dance and then - voom! - it's too late, you're a co-conspirator," laughs Tarantino, of a scene that has been labelled gratuitous by some.

"I don't even know what the hell gratuitous means," argues Tarantino. "To me violence is just one of the many things you can do in movies. Saying you don't like violence in movies is like saying you don't like slapstick comedy, like saying you don't like dance sequences. I think something's gratuitous if it's badly done. It's gratuitous if you have a musical that has six good songs and a seventh really bad one." If violence is not an issue, what of those who take umbrage with the film's spicy language, liberally peppered with political incorrectness of the racist and sexist variety?

"I just think they're a bunch of guys getting together and talking a lot of shit," he insists. "I wanted to go the opposite way of how Hollywood normally works. I wanted you to hear them say very ugly things, I also wanted you to hear them say profound things. I wanted them to come across like fucking idiots one moment and brilliant geniuses the next."

Which is, indeed, what happens, for, interspersed with lines of the "fuck you" variety is some sharp observation, not least from Mr. Pink (Steve Buscemi) who conducts a seminar on the ideological reasons for not tipping waitresses - "Jesus Christ, these ladies aren't starving, they make minimum wage" - something, like Tarantino's interpretation of the works of Madonna, which is based in reality. "That was my credo for years," he laughs. "Because when I was making minimum wage, no one was tipping me. I didn't have a job that society deemed tip-worthy."

Tarantino will, however, be able to go well over ten per cent now that Hollywood has rooted out his earlier, rejected scripts and decided that maybe they weren't so bad after all. Oliver Stone has optioned Natural Born Killers, about a husband and wife serial-killing duo, and Tony Scott - "I like Tony better than Ridley, it's not fashionable to say that, but I do" - is already stuck into True Romance, the story of another couple who uncover a cocaine cache.

Shortly heading off to raid the stationery store in a bid to finish his detective anthology, Pulp Fiction, there is no doubt that Quentin Tarantino is going through a rather, er, macho stage - in Reservoir Dogs, for instance, there is hardly a glimpse of a woman - a reality borne out by the opinions of his dear old grey-haired mother.

"She really liked Reservoir Dogs," he beams, proud of what is clearly the ultimate accolade for the current toast of Hollywood. "She just said, 'All those guys in their black suits with that music, walking together, they just look so male.' And I was like..."

Quentin Tarantino breaks off momentarily, the better to thump the table very hard indeed. "Yes! That's it... that's it..."

This article was first published in the February 1993 issue of Empire.