At the age of 82, Hollywood legend Burt Reynolds has passed away. His career spanned several decades, from seminal '70s fare including Deliverance, Smokey and the Bandit, and The Longest Yard, through to the '80s in Cannonball Run, and an Oscar-nominated turn in Boogie Nights in the '90s. In 2015, Empire's Nick de Semlyen travelled to Reynolds' mansion to interview the cinematic icon about his years in the spotlight – and you can read it in full here.

This article originally appeared in Empire magazine, issue #319 (January 2016).

His refreshments are laid out. A cluster of grapes, a glass of ice water and a bowl of Veggie Straws potato chips (‘Zesty Ranch’ flavour), arranged lovingly on a side-table.

The students are assembled. This Friday night, 18 of them have come. They include a retired Las Vegas cop, a local real-estate agent, and an actress who once played a nurse in an episode of Miami Vice. All here for the same reason: to learn from the man they sometimes call “the master”, sometimes “Mr. R”.

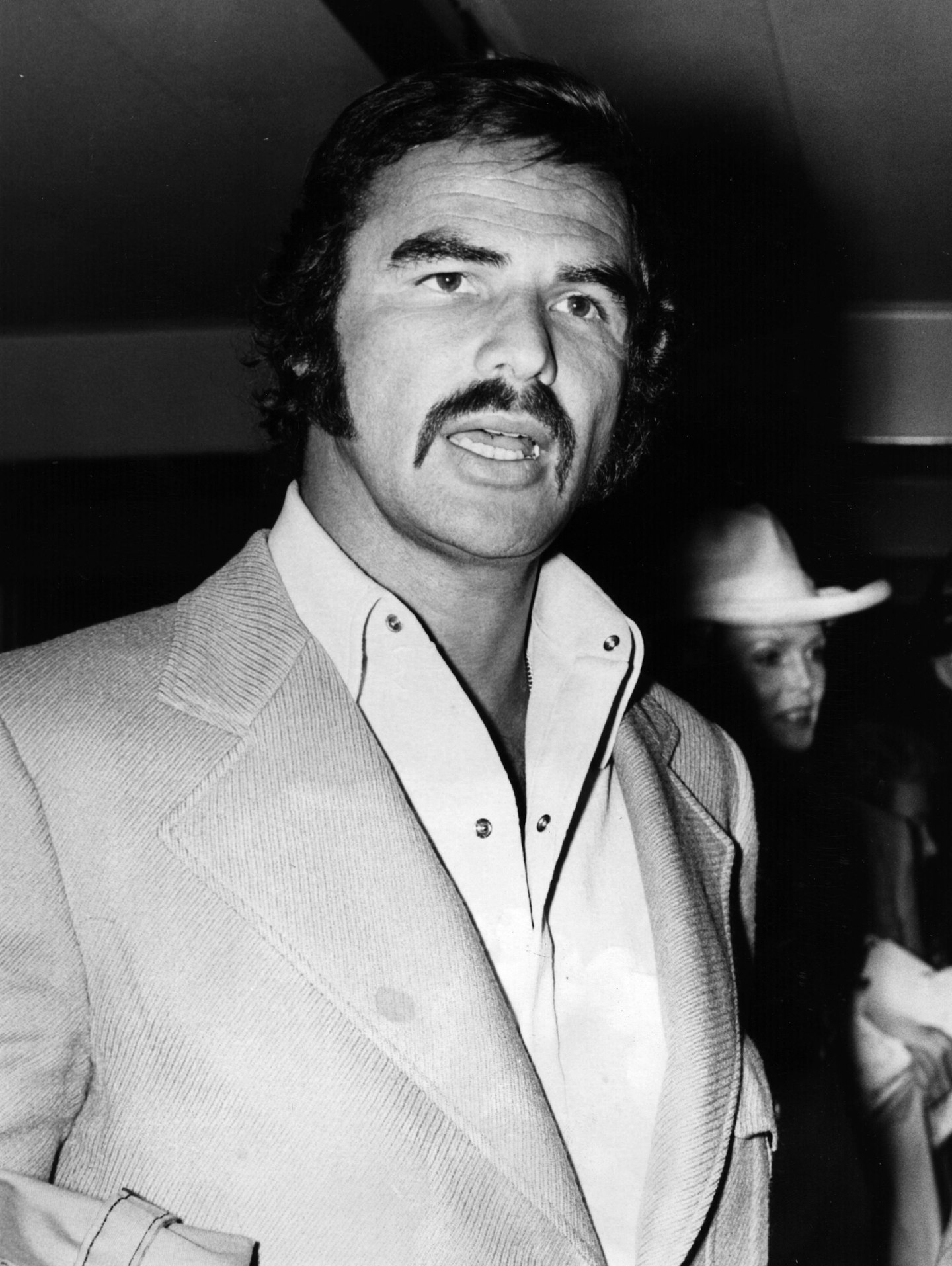

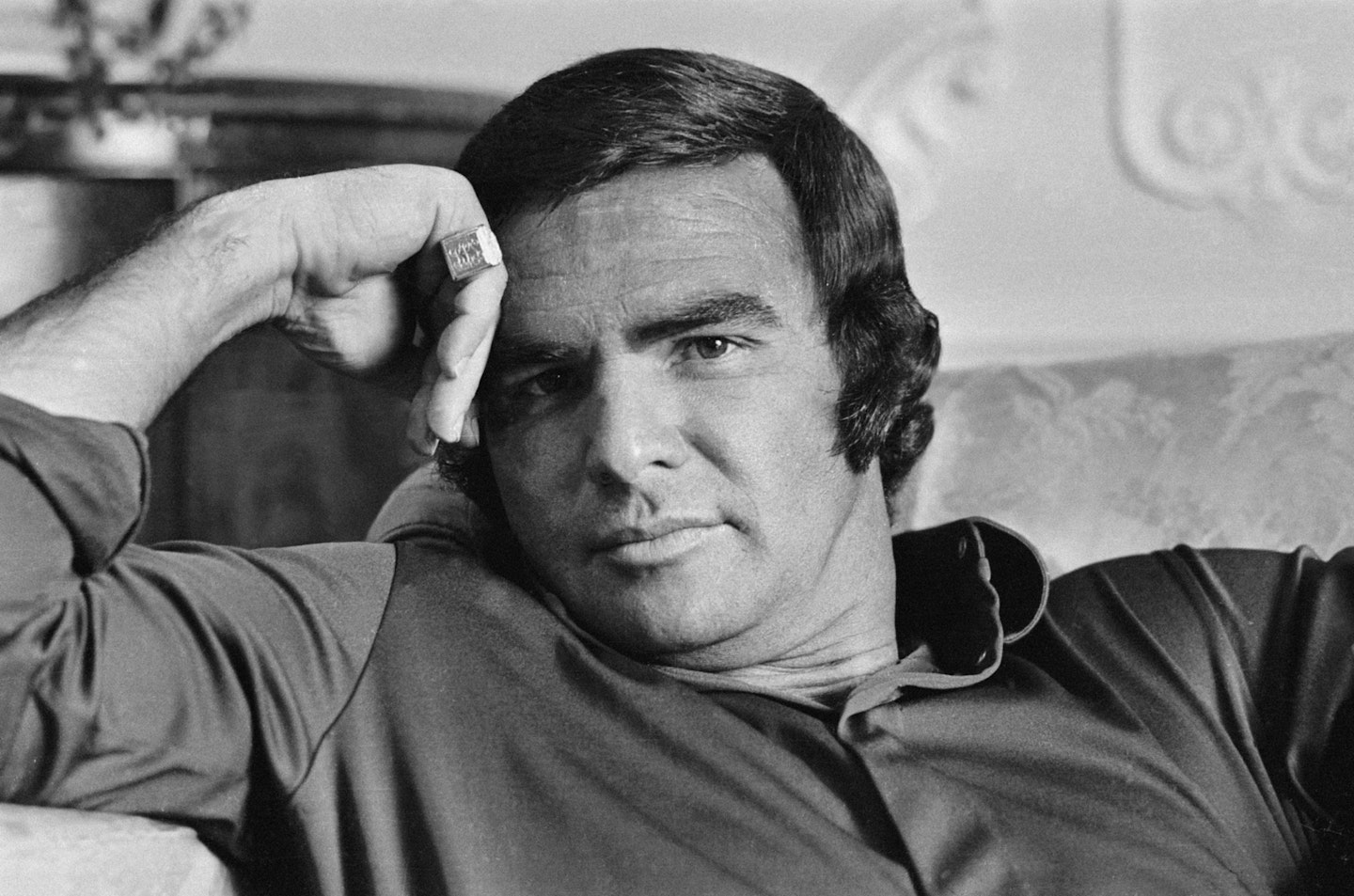

And finally, he enters. He was once the biggest movie star in the world, partying with the Rat Pack, romancing scores of Hollywood starlets, trashing an M1’s worth of automobiles. Now 79 years old, he may appear frail, moving with the aid of a walking stick and wearing red-tinted spectacles, but that magnificent moustache still commands attention. The room erupts in applause as he walks to his special seat. Then a hush takes over, pupils awaiting his opening address. “Holy cow,” says Burt Reynolds, stretching out his legs. “I’ve been working all day and I am wiped.”

These are the hallowed halls of the Burt Reynolds Institute For Film & Theatre. The name suggests a vast hippodrome, perhaps with a racetrack around the back for practising car-flips. The truth is slightly less grand. Attendees drive to the town hall in Lake Park, Florida, and head to the second floor, passing the Community Redevelopment Agency, the Commission Chambers and other municipal bureaux to slow the pulse. There, inside the Mirror Ballroom, where a mirrorball dangles from beams of Dade County Pine, they have their acting evaluated by a living legend.

It’s not easy to get in. To be invited into the $40-a-session masterclass, you must prove yourself in ‘Fundamentals’, a course focusing on character development and body language. This takes at least a year to do; some never make it through. A man in his twenties writes every month from Australia, imploring the Institute for a spot. Empire’s visit, meanwhile, marks the first time a media outlet has been invited to sit in. Rather than be thrust onto the stage to tackle some Chekhov, we’re ushered to a front-row chair beside Mr. R. From there, we watch for 90 minutes as nervous thesps strut their stuff for the Smokey And The Bandit star.

Anya and Beverly adopt Cockney accents to perform a scene from Philip Ridley’s play Vincent River. Midway through, one of them stumbles on a line, later attributing it to her new dental braces. “Y’know, it’s alright to add in a line about your braces,” advises Reynolds. “I do it all the time, and get accused of it. If they want to take it out, they can. Truth is what we want.”

Tracy, who is auditioning to join the inner circle, joins veteran Rhonda to take on a scene from Neil Simon’s The Gingerbread Lady. “That was real nice, kids,” Reynolds tells them. “Real nice. Last time one of you was ahead of the other. Today you were together. It makes such a difference.” There’s a dramatic pause, before the master delivers his verdict. “Tracy... welcome to class.”

Reynolds has spent the day in a sound booth, recording the audiobook of his new memoir But Enough About Me, and he wasn’t joking about being wiped. But now and again he drops an anecdote that reminds you of where he’s been. After another duo have channelled Taylor and Burton for a piece from Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?, he nonchalantly declares, “I remember when Elizabeth was at my house.”

That hush descends on the room once more. “She was in the bathtub,” Reynolds continues, “and I suddenly heard this scream. I said, ‘What’s the matter?’ She said, ‘They’re going to give me a million dollars for Cleopatra!’ At the time, nobody got a million dollars, especially a woman. I was so proud of her.” He lets loose one of his famous chuckles. “I said, ‘That’s great. But if you’re getting all that money, I get to jump in the tub with you…’”

If I’d said yes to Star Wars, there would have been no Smokey And The Bandit...

It was in this very room, back in 1955, that Reynolds began his ascent. A stocky 19-year-old, he’d become a star football player at Palm Beach High School but had recently injured his knee and was limping around in a funk. His English Lit teacher, an ebullient eccentric named Watson B. Duncan III, suggested he audition for the school play. “He tricked me,” smiles Reynolds, after wrapping up the class. “I started reading the page he gave me. Four words in, he said, ‘You got the main part.’”

That part was Tom Prior, in Sutton Vane’s Outward Bound, a sort of proto-Lost in which guests on a luxury liner realise they’re dead. As the alcoholic Tom, Reynolds stormed the Mirror Ballroom with a tour de force performance that bagged him the Florida State Drama Award. “I still remember being up there,” he says, gazing at the stage. “I wasn’t nervous at all. I’d been dragged to Watson’s class, a black sheep sitting at the back like all jocks do, but I slowly started moving forward. He was beyond any teacher I ever had.”

Reynolds had the bug, and over the next 15 years flung himself into every challenge that came along. There were guest-spots on The Twilight Zone and Flipper, stints on Gunsmoke and Hawk, and movies like Armored Command and Navajo Joe. Between jobs, he worked as a truck driver, bouncer and dockworker. Most character-building of all, he shared a New York apartment with Rip Torn.

“He was wild,” Reynolds says of the notoriously volatile Men In Black star. “One time they asked me to go duck-hunting in the Roosevelt Game Reserve for (TV show) The American Sportsman, and I took Rip with me. While we were walking around, some geese flew above us, squawking. Rip goes, ‘You know what they’re saying? They’re saying, “That’s the crazy Rip Torn down there.”’ He took his gun, said, ‘I’ll teach that sonuvabitch to talk like that,’ and shot one. I said, ‘Rip, you really are crazy.’ But I couldn’t help but love him. Still do.”

Reynolds built a reputation as a fearless man of action, stoked by his eagerness to do his own stunts. “The first one involved me going through a plate-glass window on a show called Frontiers Of Faith,” he says. “I got 125 bucks — a nice chunk of change in 1957.” On NBC series Riverboat, he’d ask the writers to add dangerous gags to the scripts. He felt more confident leaping off a building than saying his lines.

Then, in 1971, along came the perfect film. John Boorman had tried to cast Marlon Brando and Jack Nicholson in Deliverance, the tale of four city boys on an ill-fated canoeing trip, but retreated when they asked for $500,000 each. He could, however, afford Jon Voight and the more or less unknown Reynolds, who even looked strikingly like a young Brando. Together with Ned Beatty and Ronny Cox, the pair headed to the Chattooga River in Georgia — 50 miles of white-water hell — for what would be a gruelling shoot, beset by wipeouts, injuries and near-drownings.

“Deliverance took 14 weeks to make, longer than most films,” Reynolds says, “but it created a great bond between us. It was a skeleton crew, and I got to learn so much about what goes into directing. John Boorman is still the best I’ve ever worked for.”

He still winces when recalling the day he cracked his coccyx on a rock. “The tailbone thing was real bad,” he says. “They’d tried throwing a dummy over the waterfall. I looked at the rushes and said, ‘It looks ridiculous. I can do better than that.’ So I went over myself and got mangled in the hydroflow. When I got out of hospital, I asked John, ‘How did it look?’ He said, ‘Like a dummy going over a waterfall.’”

Oozing with backwoods menace, Deliverance was a huge box-office hit, the one Reynolds had been waiting for. Suddenly, he was on the A-list. And he’d only climb higher.

John Boorman is still the best I’ve ever worked for.

A short drive up US 1 from the Institute is Burt Reynolds’ mansion. Empire visits the next afternoon, and it’s exactly what we’d hoped it would be. Beyond a set of forbidding gates, down an impossibly long driveway with signs like “NO TRESPASSING” and “RABBITS & SQUIRRELS HAVE RIGHT OF WAY”, you find the five-bedroom house, named Valhalla after the Norse hall of the gods where fallen warriors meet their makers. Reynolds has lived here since 1980. In fact, he’s stayed in these parts most of his life; a nearby park is even named after him.

The waterfront estate’s 3.4 acres include a helipad and a yacht dock. Inside, it’s even better. Reynolds auctioned off thousands of pieces of memorabilia last Christmas, but his home remains stuffed with Burtifacts. A model railway track snakes around the ground floor. There’s a private cinema, stocked with 35mm prints of his preferred films (including My Favorite Year, all 12 reels of The Ten Commandments plus, awesomely, Moonraker and The Beastmaster). In the rec room, meanwhile, a stuffed Kodiak bear guards the wet bar. “That’s Jack,” Reynolds explains. “I worked with him a few times. I once got jammed up between him and a tiger that got loose, on a set in Florida in the ’60s. Once Jack passed away, his trainer mounted him and a few years later didn’t have any place to keep him anymore, so that’s when I got him.”

Today is a rest day; the star is dressed down, in a sports jacket and elephant-skin boots. Again he seems exhausted, speaking slowly and sometimes in a low mumble, but he’s happy to reflect on his unbelievable life. There are plenty of visual cues on the walls, like the group photo, taken at one of his birthday parties, featuring him surrounded by Frank Sinatra, Cary Grant, Jimmy Stewart, Dean Martin, Joan Collins, Sammy Davis Jr., Sid Caesar and Lucille Ball. Or the neon sign — “Burt’s Place” — from his attempt to launch a nightclub in Atlanta, complete with stained-glass dancefloor featuring a rendering of his face.

Reynolds made it big in a canoe, but it was behind the wheel that he went stratospheric. “I’m the Picasso of car pictures,” he said in 1994. If so, his Blue Period spans from 1973 (White Lightning) to 1982 (Cannonball Run II). Often collaborating with stuntman-turned-director pal Hal Needham, those nine years saw him pursued by the Highway Patrol across endless asphalt, performing ever-more-outrageous stunts. 1977’s Smokey And The Bandit, which paired him with an adorable Sally Field, was the pinnacle of his gum-chewing, beer-sipping, wisecracking persona: only Star Wars topped it at the US box office that year.

“When Smokey was released I was at my ranch with Sally,” he says. “We took a drive and saw this crowd outside the Palm Beach Mall. I thought there must have been an accident, so we pulled into the parking lot to see what was going on. And there was no accident. They were all waiting to get into the theatre to see Smokey. I actually got a little nervous.”

All his dreams, it seems, were coming true. For The Cannonball Run he was paid $1 million per week, prompting him to say, “It was immoral to offer anyone that kind of money. It would have been even more immoral to turn it down.” He was invited to the White House (“President Reagan asked me to pray with him”) and Buckingham Palace (“A manservant came out and said, ‘The Queen Mother would like to see you.’ I said, ‘Oh my God, what did I do wrong?’”). He bought a racehorse and a petting zoo. Between marriages he dated Farrah Fawcett, Catherine Deneuve and Field. He worked with Mel Brooks and Woody Allen, made a musical (“He dances like a drunk killing cockroaches,” sneered one critic), even released an album.

But not everything was peachy. For one thing, his father, ‘Big Burt’, a chief of police, seemed unimpressed. “There was always tension there,” reflects Reynolds, “because he wasn’t able to express himself. I think he was proud of me, but he never said so. It was hard for me.” For another, there was his break-up with Field, whom he still considers the love of his life. “I was so busy back then that I really didn’t take the time for myself or others in my life... I really should have taken more time to be with Sally. I regret that to this day.”

Other regrets: turning down Jack Nicholson’s role in Terms Of Endearment and 007 in Live And Let Die. “I met with (Cubby) Broccoli in Miami and told him, ‘An American can never play James Bond,’” he says. “Another brilliant career move. He must have listened to me, because there hasn’t been one. Turning down Terms Of Endearment was my biggest mistake, because Jim Brooks wrote the part for me. But I’d promised Hal I’d make Stroker Ace. I also regret not doing Zardoz (which would star Sean Connery). I got sick and wound up having to tell John Boorman I couldn’t do it. It broke his heart and I’ve always felt bad about it.”

The biggest role Reynolds claims he rejected was Han Solo. But this one doesn’t bother him so much. “I thought it was a decent picture, but I didn’t love it,” he says. “And if I’d said yes, there would have been no Smokey And The Bandit: they were filmed at the same time.” In retrospect, they make a great double bill: who is the Bandit but Solo with a less furry co-pilot and Coors in the hold? Curiously, a 1971 episode of Reynolds’ cop series Dan August features Harrison Ford in a tiny role. Hunt it down: it’s your only chance to see the man who would be Han Solo share the screen with the man who coulda been.

It was immoral to offer anyone that kind of money. It would have been even more immoral to turn it down.

Calamity struck in 1984. Reynolds was finally making a movie with old friend Clint Eastwood: Prohibition comedy City Heat. But during the filming of a bar-fight scene, somebody accidentally walloped him over the head with a heavy metal chair. He got up in agony, but carried on filming. “I didn’t want to let down Clint,” he remembers, “so I played it down. If I only knew that that was the best it was going to be for a long while, I’d have handled it differently.”

What became clear over the coming months, as he popped painkillers to get through each day, was that there was something seriously wrong with his jaw. Beset by blinding headaches and dizziness, he starting consuming up to 50 Halcion pills a day, at one point suffering a nine-hour hallucination during which he was convinced he was breakfasting with comedian Milton Berle. “That was probably the toughest time of my life,” he says. “I started losing weight and the rumour started going around that I had AIDS. I lost a lot of people that I thought were friends. But on a positive note I learned that the ones who stuck by me — Johnny Carson, Liz Taylor, Hal, a few others — were my true friends.”

Eventually he overcame both injury and addiction, but a comeback has proved more elusive. He has worked steadily and eclectically, from the reboots of The Dukes Of Hazzard and his classic The Longest Yard, to Universal Soldier III: Unfinished Business and Bean. But the closest he’s come to taking the world by storm again was 1997’s Boogie Nights. As Jack Horner, the porn Mephistopheles who gives Mark Wahlberg’s Dirk Diggler his big break, he put a dark spin on his old macho roles, earning a Golden Globe and an Oscar nomination.

Still, he’s not a fan. “I felt it glorified pornography,” he explains. “I made a lot of friends on set, but I wasn’t impressed by the Method acting going on. Mark walked around wearing a fake erection. And Heather Graham stayed in character the whole time, with half her clothes off…”

Not a complaint you expect to hear from the sex symbol who famously posed buck-naked on a bearskin rug for Cosmopolitan in 1972. Though he admits he wishes he’d never done it, the image lives on via internet memes and a recent promo pic for Deadpool, with Ryan Reynolds (no relation) recreating the pose. And this is far from his only legacy.

Edgar Wright has studied the Reynolds-directed Sharky’s Machine as prep for his forthcoming car movie Baby Driver. Tarantino used musical cues from White Lightning in both Kill Bill and Inglourious Basterds. A picture of Reynolds popped up in Bridesmaids. And after playing the Almighty in an episode of The X-Files, he recently voiced a devastatingly sexy version of himself on animated series Archer, causing a female character to sigh, “I swear to God, you could drown a toddler in my panties right now.”

All are tributes to the indomitable Mr. R: the man who has seen and done it all, who has survived bad reviews, ill health and irked ex-wives, who still insists on doing his own stunts.

Time comes for Empire to depart the master’s mansion. We shake Reynolds’ hand and leave him, surrounded by memorabilia, ursine keepsakes and a large painting of himself in his prime, stripped to the waist and rippling with muscles. It’s our last glimpse of Valhalla, the place where warriors can rest at last.

But Enough About Me is out now as a Hardback, an ebook and an audiobook.