In 1962, after giving things a great deal of thought, Aurelia Schwarzenegger called the doctor. She had been having some concerns about her teenage son, Arnold, and had finally decided to do something about it. He was, after all, an adolescent boy, and while all of his friends had plastered their walls with half-naked girls, Arnold had chosen somewhat different décor.

“She saw the photographs of muscle men on my wall and she absolutely flipped out,” Schwarzenegger recalls with a broad grin. “She called the doctor and said, ‘What’s going on with my son, can you help me? I mean, he’s 15 years old and he has all these naked men hanging over his bed. All his friends have naked women! Where did I go wrong?’”

Quite what the doctor suggested, Schwarzenegger can’t say, but he does recall the name of the “naked man” in a great many of those posters: Reg Park. Unless you’re an ardent collector of ’60s sword-and-sandal flicks, Park is just another faceless name on the IMDb. A former member of the Leeds United reserve squad, he embarked on a successful bodybuilding career, which led to his appearance as Hercules (or ‘Ercole’) in a handful of Italian-language peplum epics.

I felt destined for something bigger than staying in Austria.

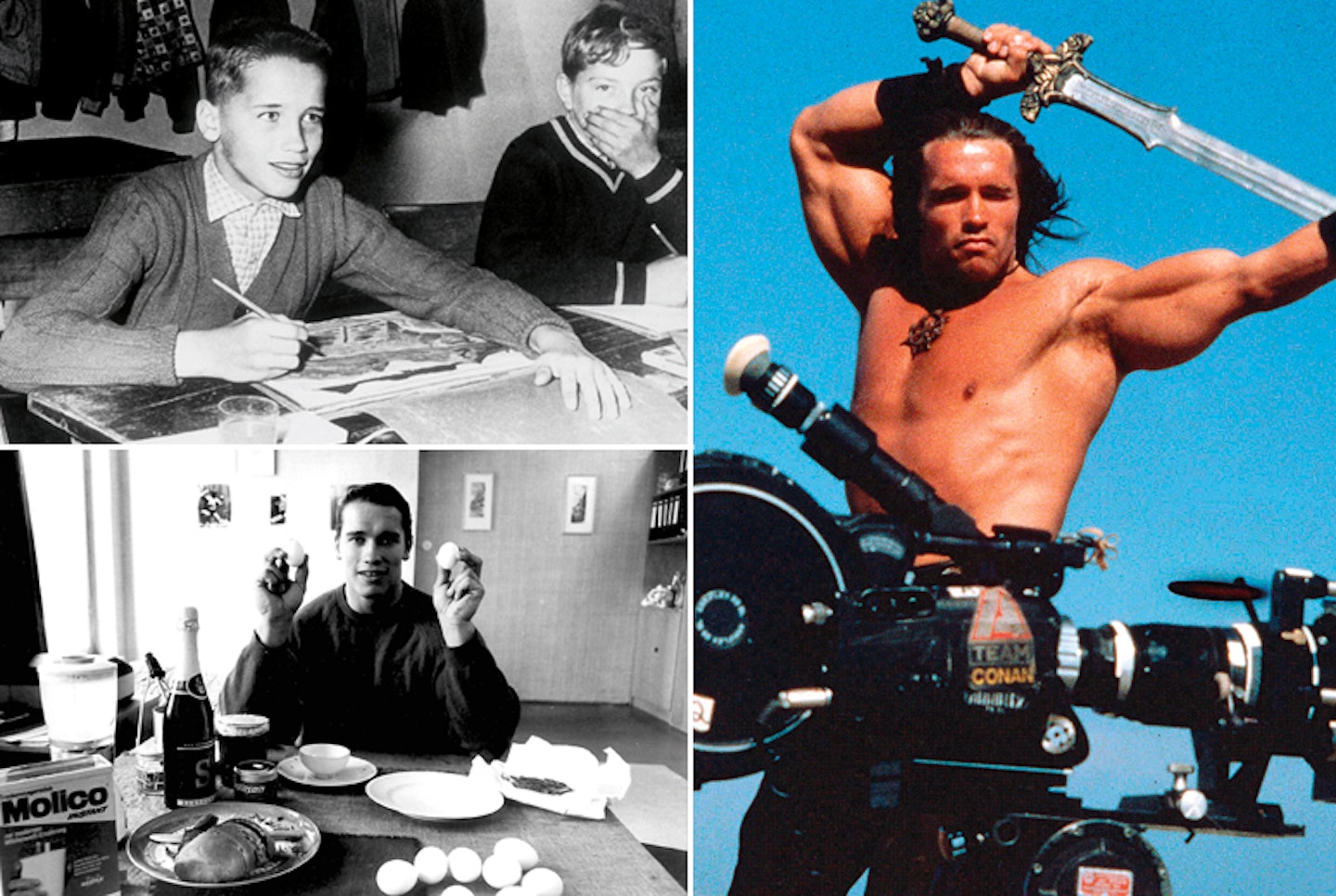

Unlikely as it seems, though, without Reg Park there would be no Arnold Schwarzenegger. At least, not the one enshrined in popular culture. The son of a local police chief, Schwarzenegger grew up amid the austerity of post-War Austria. Living with his parents and half-brother in a house with no flushing toilet, he was forged by a life of obedience under the stern rule of his father. It was in the Styrian capital of Graz, however, that young Arnold found his purpose. While browsing a store that specialised in Americana, he found amid the cowboy boots and elaborate belt buckles a muscle mag with Reg Park on the cover.

“I’d felt from the time I was ten years old that I was destined for something bigger than staying in Austria, even though, at that time, I didn’t quite know what I was going to be. I remember buying this magazine and reading about a young kid in a factory town who trained hard, became Mr. Universe and went to America. Then all of a sudden he was offered Hercules movies!

“I thought, ‘Well, this is exactly what I would like to do.’ He trained five hours a day, so I started training five hours a day. Whatever he did, I did. I basically had the blueprint for what I had always dreamed about.”

Fifty years later, Empire is standing in Schwarzenegger’s office with a sword pointed at our neck. “Here,” he says, turning the blade and passing it to us. “Try it.” Conan’s Atlantean sword, the weapon with which Schwarzenegger made his mark on cinema, is surprisingly heavy. We raise the weapon to a nod of approval and, after a few rather inexpert cuts, hand it sheepishly back to its rightful owner.

Despite the Governor’s seal still on the door, Schwarzenegger’s Santa Monica offices are like no regular politician’s workplace. The corridors are a gallery of posters for his movies and assorted, almost certainly priceless, memorabilia litters every surface. A life-size waxwork — a gift from the late Stan Winston — greets new arrivals with a classic Arnie grin and thumbs-up, while nearby a fully armoured Mr. Freeze stands with a glaring Predator. The doors to his inner sanctum, meanwhile, are flanked by a pair of Terminators. Inside, a harrier jump jet from True Lies hangs above a pool table, while Eraser’s alligator — disappointingly not luggage — lies stretched out beneath it. The overwhelming feeling is that of being inside the ultimate boy’s bedroom.

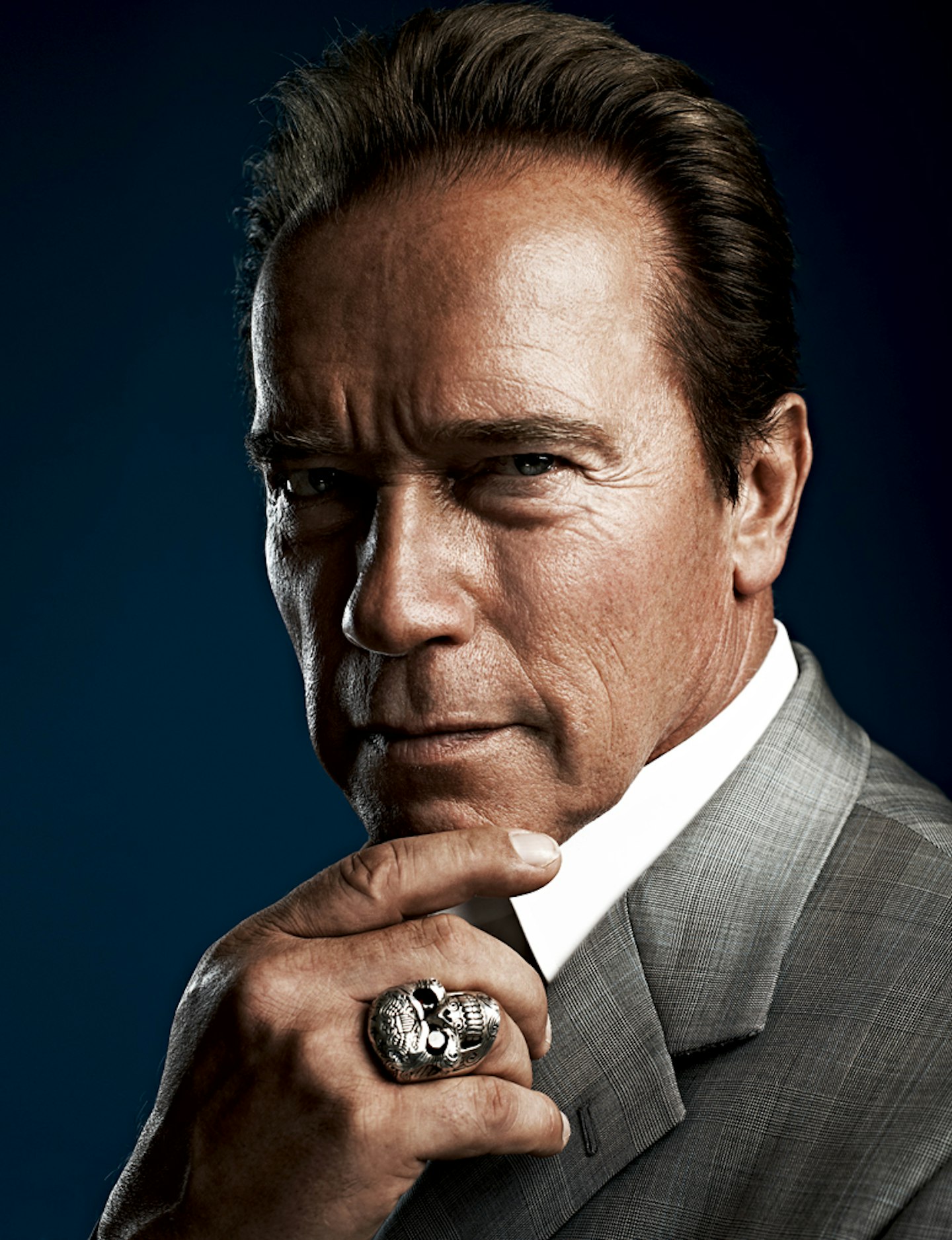

Effortlessly retrieving the sword with one hand, Schwarzenegger props it in a corner and reclines behind an enormous wooden desk. Our first impression upon meeting him is, perhaps unsurprisingly, one of size. His six-foot-two frame boasts sweeping, broad shoulders that roll out like an impeccably tailored mountain range. The effect is a looming, rock-hewn wall of a man, so broad he seems almost square: Roger Hargreaves’ Mr. Strong in a $5,000 suit.

Even his accessories are almost comically oversized. Chunky, alligator-skin cowboy boots consume his feet, while each hand boasts a single, massive ring: one of office, bearing the California governor’s seal; the other a large, grinning skull with glittering ruby eyes. Around his wrist is wrapped a colossal Panerai watch the size of a saucer: a hefty slab of metal and glass given to him by Sylvester Stallone.

He may lack some of the definition that once inspired a generation of bodybuilders, but swollen biceps still bulge noticeably beneath the sleeves of his jacket. When he first extended a pillar-like arm to greet us, his shake, while firm, was surprisingly gentle and not the joint-popping grip we had feared (or the mid-air arm wrestle a small part of us had hoped for).

He's Roger Hargreaves’ Mr. Strong in a $5,000 suit.

At 65 years old, his features are weathered yet distinguished. His jaw is a block of granite, the lines across his face the roadmap of a life well lived. He is genial, talkative and generous with his attention. His humour is often deadpan and sometimes hard to read. And despite his mileage on the campaign trail, recycling stump speeches and ducking inopportune questions, he is surprisingly forthcoming. Our eyes are drawn to the far wall, almost entirely taken up by many-tiered bodybuilding trophies. The Governor — as his aides still pointedly refer to him — immediately stands and leads us over for a closer look. There are countless accolades in bronze, gold and glass, picked up like penny sweets during the course of his career.

“When I started lifting I got compliments right away,” he says, talking us through the collection. “‘Wow! You’ve been lifting for a month? This is incredible. Look at your muscles popping out!’ It was the perfect storm. Bodybuilding got me into the movies, then the movies got me into political office — because politics is all about name-recognition. So it all goes back to bodybuilding. Without that I wouldn’t have achieved any of the things that happened after.”

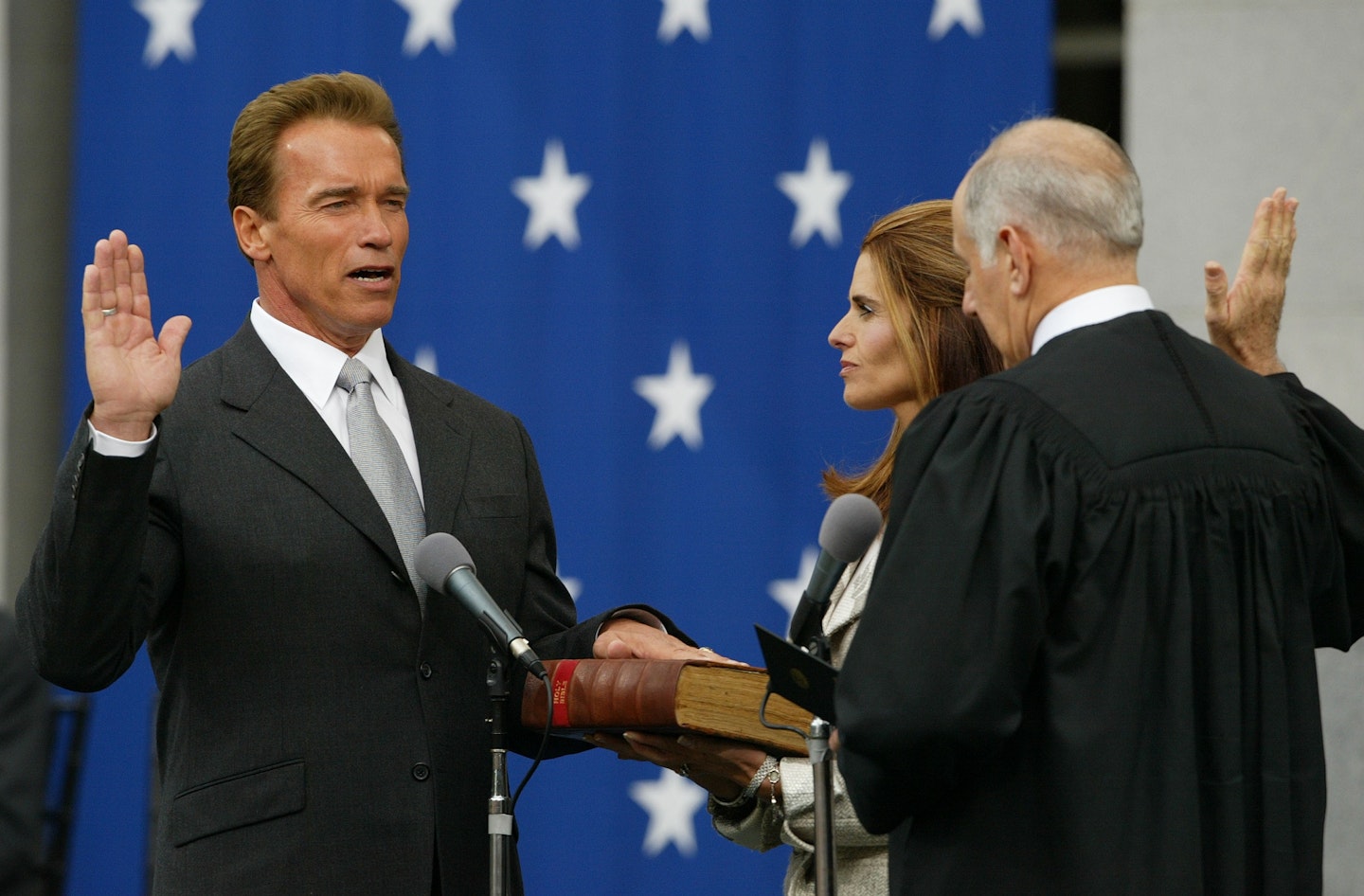

It’s been nearly a decade since Schwarzenegger stepped down from his pedestal atop the Hollywood pantheon to become Governor of California. Most of the last nine years have been spent trying to keep a near-bankrupt state from sinking beneath its debt while wrangling greenhouse emissions, partisan squabbles and tumbling approval ratings — all for no financial reward. Quite the change of pace for a man whose last film, Terminator 3: Rise Of The Machines, netted him a cool $30 million, along with the distinction of being the highest-paid actor in the world. But then, Schwarzenegger has never been someone content to sit around and enjoy his triumphs. He’s a man for whom the victory has always been less satisfying than the struggle to attain it.

Sweat, hard work and the Reg Park ideal led him to the very top of professional bodybuilding, and it was almost fate when a call came in to the Venice Beach gym he trained at, looking for someone to play Hercules in an upcoming production.

“I was not at all prepared for that,” he recalls, still with a degree of disbelief. “I mean, I had never taken an acting class at this point; I started taking them a month before shooting. It was hard trying to figure out the script — I didn’t even understand what the lines meant! I had someone translate it for me and help me with my English, with the dialect. It was kind of a crash course.”

Overdubbed to hide his accent and credited as Arnold Strong to hide his unpronounceable name, Schwarzenegger made his screen debut. But while 1969’s Hercules In New York was forgettable (the bear-wrestling sequence notwithstanding), his interest was kindled.

“It was like what they write about, you know, that someone gets discovered on Hollywood Boulevard, or you come over to America and all of a sudden you’re in the movies. I thought that was a joke, but here it was. Just nine months after being in America I was starring as Hercules. And as silly as that movie was, it got my foot in the door.”

Schwarzenegger’s English steadily improved but his accent remained near-impenetrable. Time and again casting agents told him his voice was not right for a leading role, that his body was freakish or that his tongue-tripping surname could never grace a billboard. Schwarzenegger held out. Thanks to a lucrative bricklaying business, Pumping Bricks, and some shrewd real-estate investments, he had already made his first million by the time he hit 30. Without the financial pressures placed upon most jobbing actors, he was free to turn down any role that didn’t suit him.

“I wanted to be a leading man. But it was not just that I had an accent, it was a German accent and in America that accent was scary. In tests, 60 per cent of people said, ‘This guy scares the shit out of me when he talks!’ They wanted to cast me as a bouncer or a Nazi officer. Hollywood is like that, they don’t get very creative. They won’t go against the obvious or try to go another way. Except when you become a star — then they would do whatever you demand.”

Among his many gongs, one in particular stands out: a single Golden Globe, awarded to Schwarzenegger in 1977 for his part in Bob Rafelson’s Stay Hungry. Coming off the back of an uncredited role in Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye (in which he sports a dodgy ’tache and cracks his knuckles at Elliott Gould. In his pants), Stay Hungry cast him as up-and-coming bodybuilder Joe Santo — a role that could have been written for him. The film, which billed him under his own name, properly introduced the world to Arnold Schwarzenegger, actor.

“That was the wildest thing! I was working with Jeff Bridges and Sally Field and all of a sudden I start winning awards! It was a reassurance that I was doing the right thing, that this was not some kind of strange dream.”

60 per cent of people said, ‘This guy scares the shit out of me when he talks!’

What followed, of course, was Pumping Iron, an insider documentary about Schwarzenegger’s rivalry with Lou Ferrigno for the 1975 Mr. Olympia title. It was an unexpected hit, raising the profile of competitive bodybuilding and making an overnight sensation of its leading man. It opened the door to roles like Cactus Jack, opposite Kirk Douglas, but most important of all, a cut of Pumping Iron found its way onto the desk of Ed Pressman, a producer adapting the writings of Robert E. Howard. The project was Conan The Barbarian and it was the vehicle to finally make Schwarzenegger a movie star.

Empire is huddled in the back of the Schwarzenegger motorcade. It’s two weeks earlier and we’re wending our way slowly through London’s West End. A steady hum builds to a roar as we near the crowds thronging Leicester Square, and a single refrain can gradually be picked out from the general hubbub. “Ar-nie! Ar-nie! Ar-nie!”

Half of the capital, it seems, has turned out for the premiere of The Expendables 2, and fans are packed ten feet deep behind the barriers. It’s an adoring reception from a city you could well imagine being entirely cheered out after whooping its way through a fortnight of Olympic fever. But as the car pulls in and Schwarzenegger steps out onto the red carpet for the first time in a decade, the reaction is nothing short of thunderous.

Taking in the spectacle, it occurs to Empire that there are three Arnold Schwarzeneggers. The first, Arnold, is exactly as we find him: friendly, gregarious and shot through with a wry sense of humour. He’s a man of unquashable optimism, who enjoys watching the odd UFC bout and likes to paint — mainly watercolours and acrylic. Then there’s The Governor. No nonsense, efficient and completely in control. Always making eye contact. Always playing the angles. Honed by his years in political office, this is the man who cuts the deals; who makes the decisions. Whenever a lens is pointed in his direction, The Governor is the man smiling back at the camera.

If Arnold is the man and The Governor is the institution, then SCHWARZENEGGER is the legend. Larger than life, seemingly ten feet tall, this is the man who glared down from every other movie poster throughout the ’80s and ’90s; the man who commanded $36,500 a word for his part in the third Terminator; the man whose name knows no lower case. SCHWARZENEGGER is the biggest star in cinema history — a superhuman figure, a hero out of myth. And it’s SCHWARZENEGGER that we find ourselves in the presence of as we walk beside him down the carpet.

“I told you I’d be back,” he announces to the crowd, beaming. They predictably go berserk.

Aides and publicists orbit Planet SCHWARZENEGGER like satellites as near-delirious fans hold out pictures for him to sign or simply bellow incoherently in the hope of drawing eye contact. Fellow ’80s icons Stallone, Van Damme and Dolph Lundgren all share the carpet, but it’s SCHWARZENEGGER that the vast majority of those here have camped out to see. While the likes of Statham, Craig and The Rock have gamely carried the torch, no-one could ever really replace Arnold Schwarzenegger. Deep down, there’s still a place in all our hearts that only Schwarzenegger can fill. He was, is and always will be the personification of action cinema, and when he went away, he left a gaping, Arnold-shaped hole in people’s lives.

After the surprise announcement that he was running for the governorship of California on Jay Leno in 2003 and his landslide election two months later, many feared they would never again see Schwarzenegger on screen. With an unfortunate cameo as Prince Hapi in Frank Coraci’s Around The World In 80 Days as his last hurrah, the actor became a politician and left Hollywood behind. Now it’s like he never left.

“This is not like a political rally,” he tells Empire over the tumult, pausing occasionally to scrawl his John Hancock on placards, posters and body parts. “In politics you also have the other side and we had some big protests. But the British fans were always fantastic for me. I remember the first time I ever saw people waiting for me outside, a few hundred people at the Victoria Palace when I won Mr. Universe. I always love to come back here.”

His cameo as part of a band of grizzled old men — ’80s icons one and all — blowing shit up in salute to the good old days seems an appropriate allegory for (if only prelude to) Schwarzenegger’s second coming. And if he’s been missed by the movie business over the past decade, then he’s certainly making up for lost time. Marketing hype has already begun to build for his first leading role of the comeback. Kim Ji-Woon’s The Last Stand sees Schwarzenegger as the sheriff of a sleepy New Mexico town. When Eduardo Noriega’s notorious cartel kingpin escapes federal custody and makes a beeline for the border, it’s Schwarzenegger who stands in his way. The film’s poster doesn’t look at all out of place next to the actor’s ’80s action fare. Striking a formidable pose, SCHWARZENEGGER stands front and centre. The tagline: “Not in his town. Not on his watch.” The only telltale signs that we’ve moved on 30 years are the lines on his face and the word ‘Arnold’ hanging before his name. As if anyone really needs reminding...

He told us he’d be back a thousand times and, it turns out, he meant it. “When I made the decision to discontinue moviemaking and be a public servant, I always felt like it was a hiatus — not leaving it behind but just taking a break. Kind of like Cincinnatus. He was a farmer who became the Roman emperor and went right back to farming afterwards. He gave back the ring and said, ‘Bye, I did my job, I’m out of here.’ I always thought there was something cool about that.

“Of course, that’s easier said than done because now it’s nine years later, right? So you’re 57 when you bow out, now you come back and you’re 65 and it’s a different ballgame.”

Despite the somewhat misleading poster, The Last Stand is a surprisingly age-appropriate role for Schwarzenegger, one that recognises and even plays on his status as the world’s most intimidating almost-pensioner. That “Arnold” on the poster is a nod to maturity. As Sheriff Ray Owens he’s still kicking asses and taking names, but he’s doing so with a twinge in his back and a world-weary look on his face. The Uzi 9mm, it seems, has now become a vintage Winchester.

“You have to play it so it’s believable. People know that I’m older now. No-one expects you to do the same things when you’re 65 as when you were 20.”

Next year will also see the release of Escape Plan, which reunites him once more with Stallone, taking on a supporting role as a supermax lifer at the world’s toughest prison (a penal tanker, in fact). Sporting a salt-and-pepper goatee to complement his grey prison attire, Schwarzenegger cuts quite the figure as a philosophical con, running the penitentiary in all but name and ultimately aiding in Stallone’s ambitious break-out. That it’s not another star vehicle is telling, as is his follow-up, David Ayers’ Sabotage (formerly Breacher), which begins shooting in October. An ensemble piece co-starring Sam Worthington and Terrence Howard, the film casts Schwarzenegger as the head of a corrupt DEA task force whose members are gradually falling to foul play. The choices show a more mature approach to his roles, more collaborative and also more cautious.

“All of these projects are appealing because they give me the chance to slowly come back rather than rush into it. I like the idea of starting again, but trying to come back halfway down and working my way slowly back up again. So that’s the idea, to do more personal stories and ensemble pieces like Predator. Breacher, especially, will be very like a new Predator. It’s a team around me and they get knocked off until there’s only me left. Except in this case there will be a different twist to the whole thing instead of some alien monster.”

It’s a remarkably self-aware attitude for a man who has spent his entire career at the very front of the pack. But then, Schwarzenegger is entirely dismissive about his level of fame.

“I’m not as much into reflecting, on looking back and saying, ‘Wow, look what I’ve achieved.’ I do think it’s incredible when you have so many ‘experts’ tell you that it will never happen and then you prove the opposite. Nelson Mandela said, ‘It always seems impossible until it’s done.’ And that’s exactly what I’ve proven. I shoot for the stars and then whatever happens, happens.”

Opposite the lifts in the entrance to Schwarzenegger’s Santa Monica offices, two entire walls are taken up by a large black-and-white mural of Hollywood’s golden age. In it, Marilyn stands with dress billowing in The Seven Year Itch, while Shirley Temple peeks shyly over a wall and Katharine Hepburn, hands on hips, stares down at a smiling Cary Grant. Around them Chaplin, James Dean, Bette Davis and even King Kong are arranged in a constellation of cinema’s most influential characters. At the far end, in striking colour, is painted a huge explosion of bricks and shrapnel with Schwarzenegger as The Terminator bursting into the scene with a grenade-launcher while Bogart and Bacall stare in mute disbelief.

Few things could serve as a more apt metaphor for Schwarzenegger’s assault on Hollywood. He emerged at a time when audiences were perfectly primed to accept him. Seventies thrillers like Death Wish and Dirty Harry had laid the groundwork with right-wing parables of one-man armies dispensing street justice. As the ’80s rolled on and everything from hairstyles to shoulder pads grew bigger and more outlandish, so too did the action stars: their inflated muscles matched only by the size of their balls. Cold War frustration and a healthy dose of Vietnam revisionism brought us Chuck Norris’ Missing In Action, Invasion U. S. A. and The Delta Force. Sylvester Stallone, meanwhile, churned out increasingly outrageous Rocky and Rambo sequels. It was the age of what Stallone would later refer to as “male pattern badness”, and if he, Norris and Van Damme were the genre’s champions, then Schwarzenegger was its king.

In the ’80s: if you had the body and could act a little bit and had some talent with fight scenes, then you were in.

“The ’80s was a time when studios started rethinking and looking at B-movies, suddenly, as A-movies,” he says, dropping a mint into his mouth in lieu of a cigar. “There was also the effect that women’s liberation had. Men felt threatened by the women’s movement, women taking over the job market and taking over sexually. Action movies became the outlet where these guys could all run to and still feel like He-Man. But specifically action movies where heroes looked the part.

“It was like in the ’60s when all of those bodybuilders — Reg Park, Steve Reeves, Gordon Mitchell — all went and did those Hercules movies. It was the same in the ’80s: if you had the body and could act a little bit and had some talent with fight scenes, then you were in.”

While Conan put Schwarzenegger on the map, The Terminator was the film that sent him into the stratosphere. Orion co-founder Mike Medavoy suggested Schwarzenegger for the project, arranging that lunch with the film’s young director, James Cameron, so he could assess Schwarzenegger for the part of the hero, Kyle Reese. Cameron was not convinced. But as the pair kicked about ideas for the role, conversation kept turning to the film’s robotic villain.

“Reese was a very interesting character, but I was fascinated with the Terminator,” Schwarzenegger recalls. “Even though I didn’t want to play it, I wanted to make sure that it was done right. Jim was this young director who had only done one movie before this and I had a vision of what needed to be done to play this character well. I wanted to explain that it’s very important, whoever he hires, that the Terminator has to train with all of the weapons stuff for real. I said to him, ‘The guy has to take the weapons apart and he has to put them together blindfolded. He never has to look down when he puts a magazine in or puts a bullet in the chamber. He has to be like a machine, with no heart and with no emotion there whatsoever.’

“Once we were through he says to me, ‘Why don’t you play the Terminator?’ I said, ‘No, no, no, I’m not here to play the Terminator, I’m here to play Reese. That’s what my manager said I should meet you about.’ But he said, ‘Just think about it. Trust me. Re-read it and let me know.’ And that’s what I did.”

Had Cameron cast Lance Henriksen in the role of the killer cyborg as he’d originally intended, things might have gone very differently. The film proved successful beyond anyone’s expectations. Its relentless antagonist was perfectly encapsulated by the hulking Austrian, his distinctive drawl only enhancing its menace. The role became a cultural icon that not only defined Schwarzenegger’s entire career, but also became an indelible part of the public consciousness.

Ironically, the scary accent that had proved such a barrier in the past and caused John Milius to make him repeat each line 40 times prior to shooting on Conan was suddenly a major selling point. Throwaway lines from The Terminator took on cult appeal when delivered in Schwarzenegger’s thick, Austrian tones, and he was soon the most imitated actor on screen — if not always flatteringly.

“I was shooting Red Sonja, in Rome, when The Terminator came out in America. I remember that when I got back, I went to New York and I had people come up to me and say, ‘Do the line, Arnold! Say the, “I’ll be back,” line.’ I didn’t even know what they were talking about. But I started to hear it more and more often. People really got off on it.“As a matter of fact, I argued with Jim Cameron about whether I should say, ‘I will be back,’ as it sounded stronger, more machine-like. He said, ‘I wrote it and it’s, “I’ll be back,” so do me a favour and just say it.’ We argued about it but I didn’t understand why that would be an interesting line at all. Maybe he did.”

The man most directly responsible for establishing the Arnie one-liner was Steven E. de Souza. In scripting the gloriously daft Commando, de Souza equipped Schwarzenegger with an arsenal of ludicrously over-the-top sign-offs and asides that would forever go down in history. “The voice became an important thing; my pronunciation of words. Instead of saying, ‘It’s not a tumour!’ in Kindergarten Cop, it was, ‘It’s not a doo-ma!’ When I’m walking around, people come up and say, ‘Arnold, Arnold, say “Get to the chopper!’’’ They just want to hear the way I say ‘choppa!’

“In most cases I did not know which line was going to hit. I mean, sometimes you do know, like in Commando when I said, ‘I lied,’ and then I dropped the guy — I knew that could get a big laugh if it was said very straight. The key thing with those lines is you have to say it straight — as soon as you try to be funny, it won’t work. You can’t put on a big smile, but there is always a little ‘Arnold spin’ on the line.”

If you'd been a visiting dignitary during Schwarzenegger’s term in office, you might have been presented with a very special gift: a bronze box, bearing the California Governor’s seal in gold, engraved with the following: “Films are more than merely images on a screen — they are places in our heart. They take us across oceans, back in history, and into the future. Please enjoy these great movies — Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger.”

It’s a sentiment that could as easily be applied to the man himself. Schwarzenegger’s connection with audiences is as much an emotional one as it is a reaction to his impressive filmography. His is an allure that harks back to a time of more unrestrained, less cynical filmmaking — a time when giant personalities dominated the industry, all but overshadowing the films they starred in. He was the 3D. And we loved him.

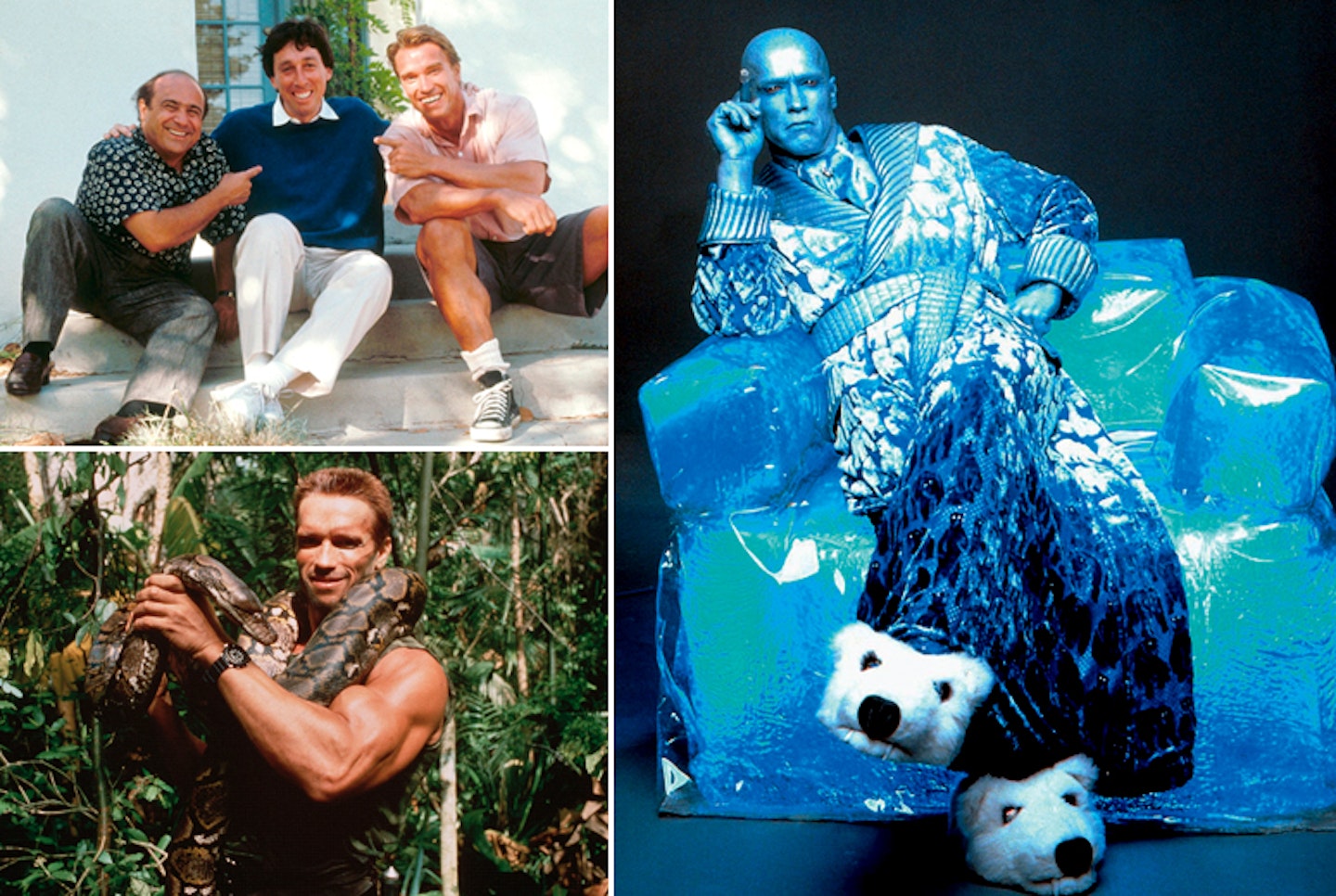

The bronze box itself contains DVDs of his ten favourite films. They are, in no particular order, Lawrence Of Arabia, Ben-Hur, Doctor Zhivago, Fantasia, The Godfather, High Noon, The Sound Of Music, Titanic, Terminator 2 and Twins. “Twins is my favourite role,” he enthuses, when we raise an eyebrow in surprise. “It was something people hadn’t seen from me before: the shy Arnold, the softer-spoken Arnold, the humorous Arnold.”

In the late ’80s, a film needed only one word on the poster to guarantee its success: Schwarzenegger. With that single word, audiences knew exactly what it was they were signing up for. That is, until the actor threw an unexpected curveball with the Ivan Reitman film.

“I was in Aspen, I remember, hanging out with Robin Williams and a bunch of other people. Ivan came over to me while we were all sitting around the fireplace at the lodge, all laughing and having a good time, and he said, ‘You know, what I saw tonight, your humour, I’ve never seen any of that on screen.’ So I said to him, ‘Well, what’s holding you back? Write something for me!’”

Reitman came back with five separate ideas for Schwarzenegger (among them later Hulk Hogan vehicle Suburban Commando) and the pair settled on a mismatched buddy movie, then called The Experiment. The studio wasn’t sure about it, nobody wanted to pay for it (Schwarzenegger passed on a salary, accepting a back-end deal), but people loved it. Pairing Schwarzenegger with pint-sized comedian and former Taxi star Danny DeVito, Twins proved a massive success and took over $217 million against a $15 million budget. With that one film the action icon had, implausibly, become a comedy sensation.

“I had thought about doing comedy before,” he insists. “Because I feel very strongly that everything in life, no matter how serious it is, has a comedic side to it. That’s why I was a big admirer of James Bond movies. Sean Connery and Roger Moore were such experts in that. I admired that and I thought, ‘I want to be able to do that.’”

Wisely, comedy is very much on the comeback agenda — he’ll soon return to his treasured role as Julius Benedict in Ivan Reitman’s sequel, Triplets, this time with Eddie Murphy as yet another offspring from the first film’s “sperm milkshake”. It is, we can imagine, very much a labour of love for Schwarzenegger.

I like the idea of starting again. Working my way slowly back up.

The fact that the other Schwarzenegger film in his Governor’s gift set is Terminator 2 comes as far less of a surprise. The film that reunited him both with James Cameron and the part with which he was most identified was the pinnacle of his success, and it’s not hard to see why. The creative team of Schwarzenegger and Cameron was lightning in a bottle — a partnership the likes of which Hollywood has rarely bettered — and Terminator 2 was the pair at their very best. With a budget of $102 million, it was a dramatic step up from its B-movie predecessor and stands, even now, as one of cinema’s greatest sequels. Schwarzenegger’s return to the iconic villain, this time repositioned as the hero (seen as a big risk at the time), sent Arnie fever into overdrive, seeing his face plastered everywhere from bumper stickers to crisp packets. When the film went on to gross more than half a billion dollars it confirmed him as the most bankable star in the world. It is the wit and emotion Cameron so brilliantly programmed into the Schwarzenegger action formula amid the special effects that we have so sorely missed.

T2’s success, however, only emphasised the disaster that followed. 1993’s Last Action Hero was Schwarzenegger’s first turkey and, as missteps go, it was a bone-shattering plummet down an open manhole. While written as a parody of Hollywood action blockbusters, squabbles over tone and a repeatedly rewritten script soon turned this meta-satire (which was apparently lost on half the production) into exactly what it sought to lampoon. Massively hyped, the film was an overblown mess and an embarrassing misfire for Schwarzenegger, and remains a cautionary tale against the hubris of success. “It was too bad because John McTiernan is a very talented director and he did such a great job on Predator and then on Die Hard. This movie should have been our biggest and it just wasn’t.” Schwarzenegger seems genuinely disappointed at the memory.

“Whenever you are on top the media is gunning for you, waiting for some vulnerability. If they see one little crack then they move in and that’s what happened. But it’s not something to be terribly upset about. One year I got all the great write-ups, that year I got the beating — it’s part of show business and it’s part of politics.” He pauses, thinking, then cracks a smile. “But I always say, ‘If you can’t take the heat, get out of the kitchen.’”

However, Last Action Hero (which has its adherents) was nothing to Joel Schumacher’s Batman & Robin. Paid an astonishing $25 million for his role as Mr. Freeze, Schwarzenegger’s performance was little more than a string of lamentable cold puns (“You’re not sending me to the cooler!”) that were laughable imitations of his once signature quips. Sporting head-to-toe silver body paint, smoking a silver stogie in a silver robe, with polar bear slippers on his feet, Schwarzenegger had hit a career low, and the film was mauled by critics. Schwarzenegger remains defiantly unrepentant. “I don’t regret it at all. I felt that the character was interesting and two movies before that one Joel Schumacher was at his height. So the decision-making process was not off. At the same time I was doing Eraser over there and Warner Bros. begged me to do the movie.

“In most cases I don’t regret the movies that failed or were not as good. It’s always easy to be smug in hindsight, right? To look back and say, ‘Oh man, I should have tweaked that script a little bit or had a different ending.’ But when you’re me, you can never complain. Because with the ride I have taken in my life, from the time I came off the farm in Austria to here today and all the things that I’ve accomplished, I really cannot complain about anything. It’s life that you make wrong decisions as much as you make good decisions and that you do great things and that you also fuck up.”

Above all else, Schwarzenegger is extremely engaging company, and a highly entertaining storyteller. He recounts a demented dream he once had while on prescription medication that involves his political opponents, killing sprees and a lion. It’s laugh-out-loud funny — and he does, almost all the way through. Then there was the time legendary ’80s producer Don Simpson burst into his trailer “totally stoned”...

“Just wiped out,” he recounts, animatedly. “He has 85 pages with him and there are handwritten notes all over it by Jerry Bruckheimer. He says, ‘Here, look at this script. But don’t read it! Just, here’s what the premise is...’ He was all over the place. I said, ‘Look, Don. I can’t make a commitment based on what you’re showing me here. You won’t even let me read the script! Why don’t you bake it some more, develop it some more and then we’ll talk again.’ He was very upset. He just walked out and then went to Nicolas Cage with the part.”

He just walked out and then went to Nicolas Cage with the part.

The not-quite-script in question was Michael Bay’s The Rock, and in some alternative universe there’s a very different film available with Schwarzenegger in the role of Dr. Stanley Goodspeed. It’s quite possibly the same universe where he snaps Alan Rickman’s neck before hurling him through a plate-glass window as indestructible supercop, John McClane. “It was the same with Die Hard. There was an unfinished script, which someone gave me and said, ‘Would you want to play this?’ I was working with Joel Silver on Predator and Die Hard was his next movie. So we talked about it but then he hired Bruce Willis.”

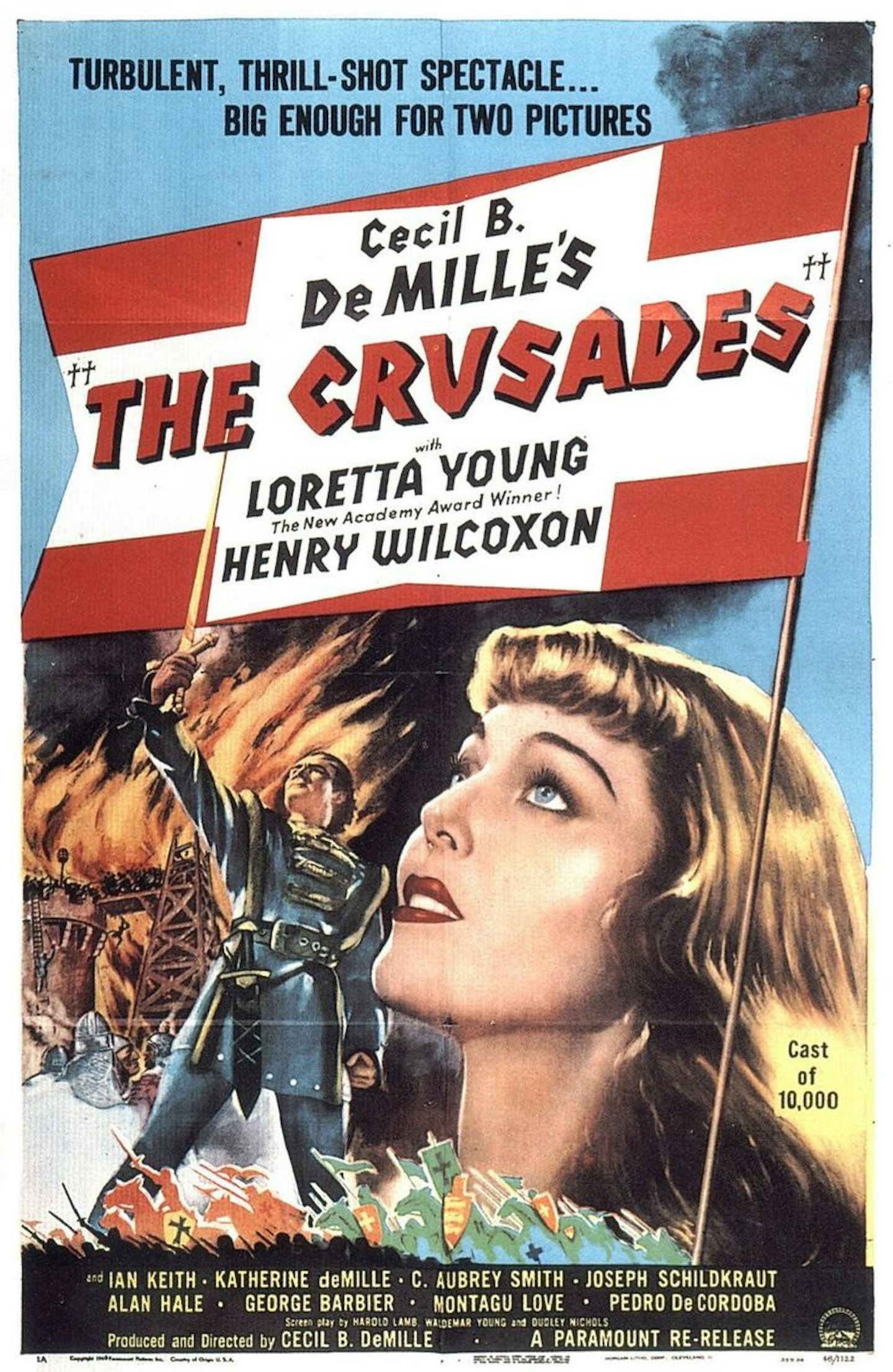

While listing other roles he never took, Schwarzenegger startlingly mentions Full Metal Jacket’s Animal Mother (“I didn’t have the time to do it”). Imagine it, Schwarzenegger and Kubrick — what a match. More predictably, but equally as enticing, there was Doctor Octopus in Jim Cameron’s sadly abandoned Spider-Man adaptation (“It never got there because he had a battle with the studio and they went in a different direction”). But, as he’s already told us, Schwarzenegger is not a man who has regrets. Not about anything? We gesture to a large frame at the back of his office, which houses a poster for Cecil B. DeMille’s 1935 epic, The Crusades. Surely a wistful nod to what could have been if Paul Verhoeven’s hugely ambitious and ruinously expensive Crusade had ever got off the ground 20 years ago?

Schwarzenegger walks over to stand before the poster, which is a good seven feet across. “It was all written and ready to go but then Paul started going crazy. We had the final meeting with the studio and we were all sitting at this boardroom table. They said, ‘So the budget is $100 million. That’s a lot of money. What kind of guarantees do you have that we will get it for 100 and it won’t go up to 130?’”

Verhoeven, not the world’s most temperate soul, used this inopportune time to protect his artistic rights. “He says, ‘What do you mean, ‘guarantees’?'” booms Schwarzengger — Dutch doing Dutch. “'There’s no such thing as guarantees! Guarantees don’t happen and if anyone promises you guarantees, they’re lying! We don’t even know that if you walk out of the building here you won’t get hit by a truck. There’s no guarantee that we’re going to make it ’til tomorrow! I cannot have control over God — I don’t even believe in God, why am I talking about God? But someone, nature, could just rain for three months and then what do we do? How can I give you a guarantee? This is ludicrous!’ I kept kicking him under the table and trying to tell him to shut up while we’re ahead. But he just wouldn’t, and that was it. That was the end of that movie. Paul always tried to be honest, but you can be a little bit selective about when to be honest and when to just move on with the project. It was a shame.”

We ask about the scripts that must now be piling up on his desk. He mentions a Western, Outrider, which he was working on before he went away and has now dusted off — with a few accommodations for age. Could this be Schwarzenegger’s Unforgiven? We enquire about the story, only to have him blithely ruin the ending. Unbelievably, he follows this up with a colossal spoiler for Sabotage as well. We hastily steer the conversation to safer ground. Would he return to his other favourite role? Is there room, we ask, for a Schwarzenegger Terminator in a post-McG world?

“I think (producer) Megan Ellison owns the rights to Terminator 16, or whatever it is.” Five, we supply helpfully. “Yes, five. They have been trying to put a script together but I’ve not seen it, so I’ve no idea. There’s nothing on the drawing board at this point. Nothing on the plan.” Whether, at his current age, he could believably reprise the role is another matter. He is forced to look at all roles in a different light now, keeping a shrewd eye on what will or won’t fit with his new, less over-the-top image.

It's just life that you do great things and that you also fuck up.

“In the end you perform for the people,” he says, sitting back. “When you’re not believable as the guy doing high kicks and flying through the air then you have to punch up other areas and rely more on drama. This change and what happens in the near future with my movies is all going to be a good experience for me. I have to broaden myself, expand and concentrate on the acting and on the characters.”

Unlikely as it might seem, the former king of carnage may even step behind the camera. After all, it wouldn’t be the first time. He directed twice in the early ’90s — a TV remake of Christmas In Connecticut and an episode of Tales From The Crypt. “I had a terrific time,” he says, “but there’s the whole pre-production and then the months of post-production. I didn’t have the patience! But that doesn’t mean that I’m not going to now. I maybe will try again if something comes along.”

The fact is, with his enormous wealth, extraordinary fame and towering collection of trophies, Schwarzenegger can do whatever the hell he wants. He is, in many ways, an anachronism plucked from his own time and deposited here, in the future. Yet far from being obsolete, his return feels like a breath of fresh air. Mired in endless remakes, reboots, sequels and spin-offs, what Hollywood needs now, more than ever, is personality. And personalities don’t come any bigger than Arnold Schwarzenegger. He was the most influential bodybuilder in the history of the sport, the last word in action films for more than a decade and leader of the world’s eighth-largest economy. His is among the ten most recognisable faces on the planet and he remains one of the most successful movie stars ever. And he’s back. So what if, once upon a time, his mother was concerned about the naked men stuck on his wall?

“There were no naked men,” he says, suddenly serious. Then smiles. “They were always in trunks or a loincloth.”

This article first appeared in the November 2012 issue of Empire{