As both a novelist and screenwriter, Alex Garland has repeatedly tapped the dramatic value of the claustrophobic community: the crusty utopian tribe of The Beach, the odd school of his Ishiguro adaptation Never Let Me Go, the locked-down mega-tower-block of Dredd. Now, with his directorial debut Ex Machina, he pushes this further yet: three characters, one remote location. It is as if Garland has been perfecting a formula over the years. And, if you’ll forgive the mixing of scientific metaphors, he may well shout “Eureka” with Ex Machina, as it is his most successful and satisfying creation yet. There are some big ideas housed in these closing walls.

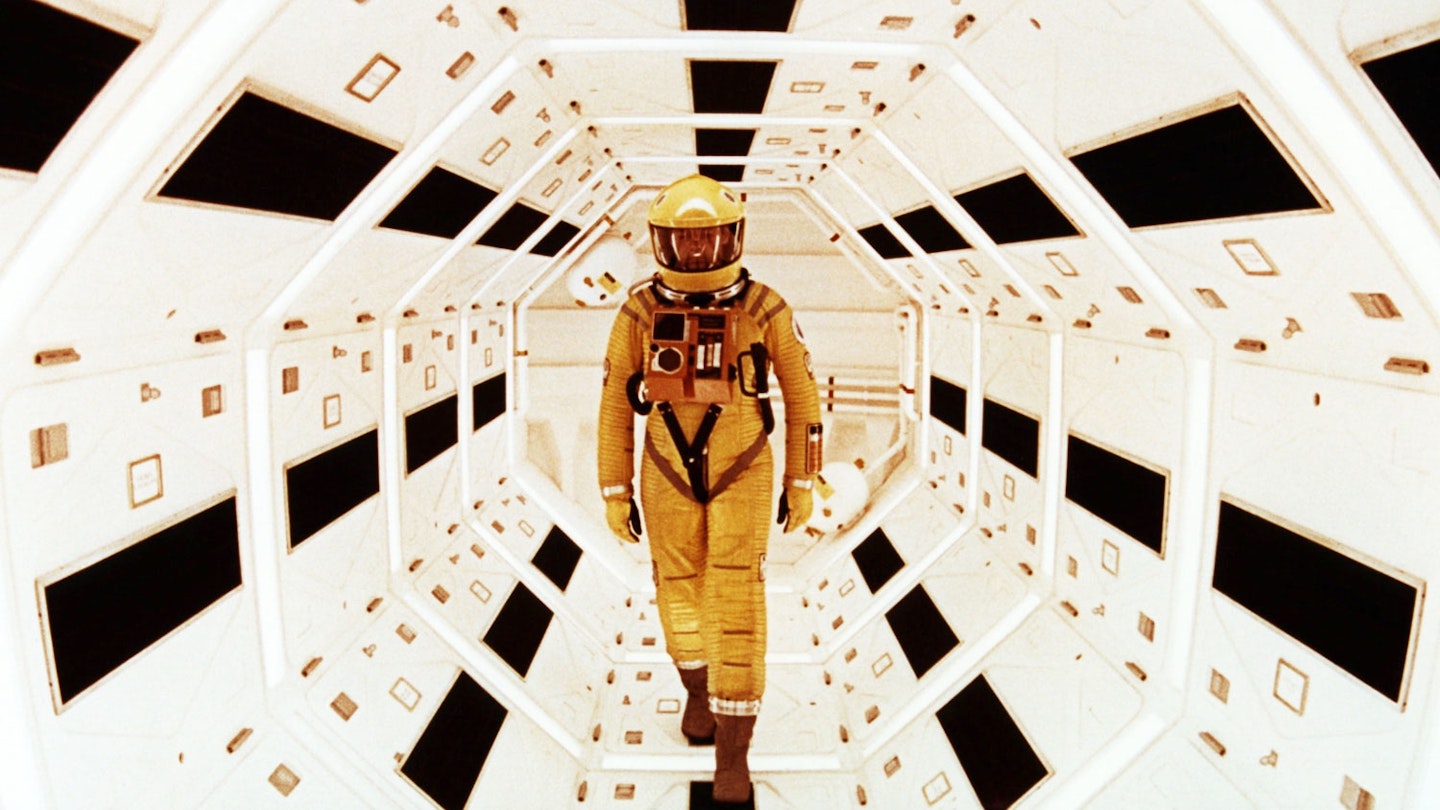

Ex Machina is old-fashioned, grown-up science-fiction. It is executed with the scrutiny we’d expect from a Kubrick or (more recently) a Nolan, but it has a darkly satirical pulse too that distinguishes it and warms its appeal. At one point, Garland throws in an unexpected and cheeky reference to Dan Aykroyd’s spectral blow-job in Ghostbusters; at another, there is a spontaneous disco freak-out to Oliver Cheatham’s Get Down Saturday Night.

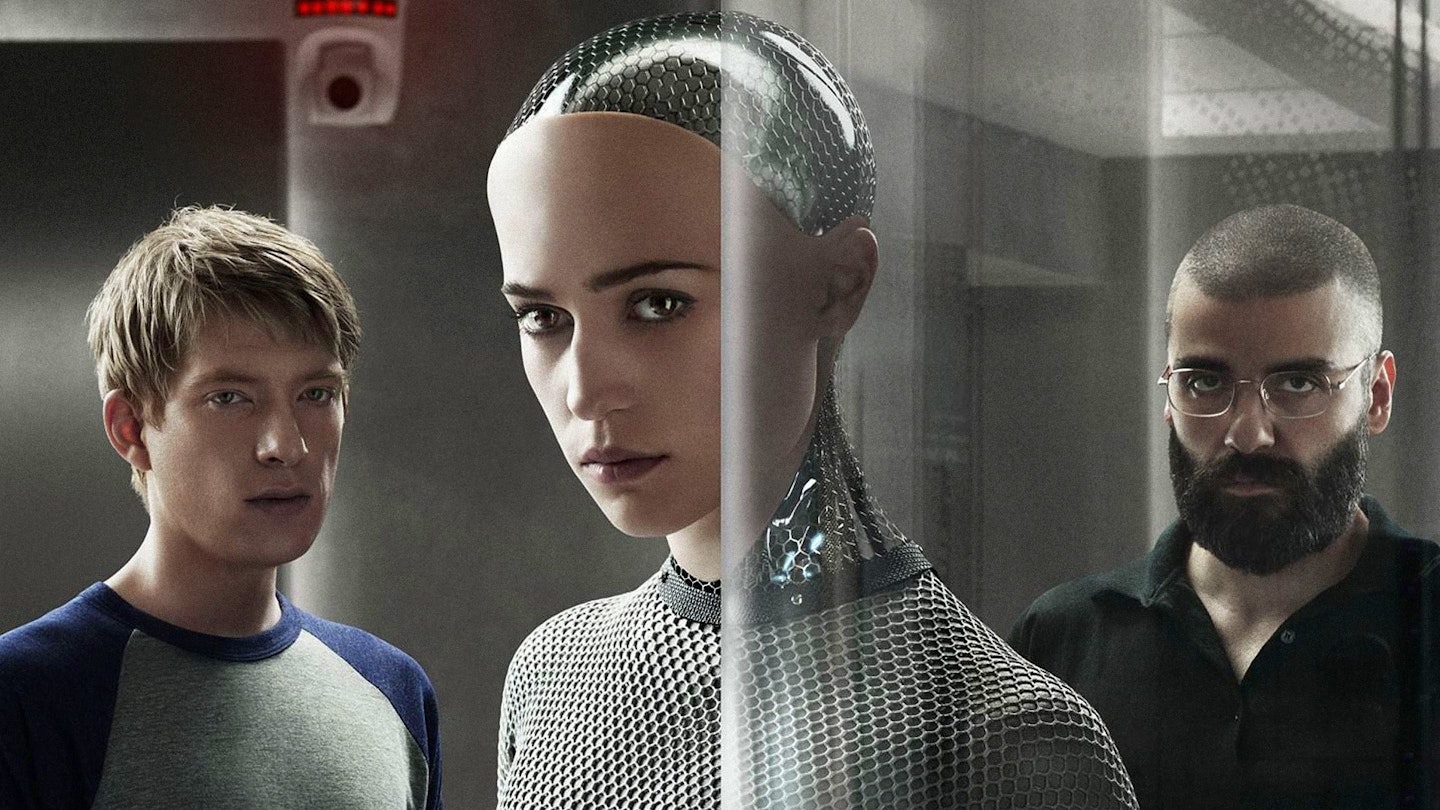

Which in no way means Ex Machina doesn’t take itself seriously. Its bursts of relative levity apply a layer of discord to a plot that ratchets tension from the very moment of Caleb’s (Domnhall Gleeson) arrival on Nathan’s (Oscar Isaac) vast estate, which, with its sterile atmosphere, exquisite rockeries, waterfall-straddling aspect and weirdly handle-less doors wouldn’t look out of place in the third act of a Bond movie. And when Caleb reluctantly agrees to sign “the mother of all NDAs” and consents to staying in a windowless basement room, you get the unsettling sense he’s voluntarily incarcerating himself… with Silicon Valley’s answer to Dr. Moreau.

It might be harder to swallow if it weren’t so well played. Steady rising star Gleeson plays Caleb as polite and diffident, yet sharp and trauma-hardened. In contrast, Isaac (who of course will be Gleeson’s co-star in Star Wars The Force Awakens), imbues tech-mogul Nathan with the tarnished glamour and aggressive self-assurance of a jaded rock star. He’s a peak-bearded alpha male whose ego is so all-consuming he only needs himself to party, and who pummels punchbags as a hangover cure. Then there is Alicia Vikander (who of course was Gleeson’s co-star in Anna Karenina) as Ava.

With the help of Double Negative’s laudable VFX, Ava is familiar, recalling Sonny in I, Robot and Bjork in Chris Cunningham’s All Is Full Of Love video, yet unique, with a glowing midriff power-core on display. Her heart, in a sense, is for all to see. But it is Vikander’s possession of the spirit in this machine which truly marks Ava out. With a ballerina’s poise, her every movement from footfall to facial twitch is performed with pinpoint precision; mechanical enough for her to convince as an automaton, with an organic tactility which nourishes her impressive chemistry with Gleeson while the pair get to know each other from either side of a Silence Of The Lambs-ish glass screen.

For all her co-stars’ fine work, Vikander is the star here, and flourishes under Garland’s steady gaze and guidance. Between them, director and actress may even have crafted an icon — both sci-fi and, surprisingly, feminist.