There have been many Draculas. But the one against which all others are measured is Bela Lugosi. Tod Browning's 1931 film is stagey and creaky, but it also has wonderful, unforgettable moments. Lugosi's performance is, on one level, high camp. Yet when he says "I am Dracula," by God he means it. When we're talking about the blood-sucking undead, he simply is the man. Stoker's novel, published in 1897, has proved as irresistible for dramatisation as his vampire's magnetic power over his victims. Stoker himself (business manager of London's Lyceum Theatre) turned it into a play which was never produced. Then in 1921 a Hungarian silent film, Drakula's Death (now lost), used a different plot entirely but borrowed the name. F.W. Murnau's Nosferatu is the eeriest version of all and bequeathed Max Schreck's repulsive, ratlike vampire to our collective nightmares.

In 1924 in London, Hamilton Deane wrote an authorised stage version of the book which pared down both plot and characters. It was critically derided but was nevertheless a hit. And it's to this version that we owe the image of the vampire as a suave man-about-town decked in immaculate evening dress. When it reached Broadway in 1927, re-written by John Balderston, it provided the big break for Hungarian emigre Bela Blasko. Bela's exotic accent and sinister charisma regularly had women fainting in the aisles. Universal's plans for a faithful adaptation of Stoker's novel were abandoned in favour of the simplified play when the Great Depression left them strapped for cash. They were also strapped for a star. It was intended as a vehicle for Lon Chaney by his favourite director, Browning, whose flair for the macabre had been amply demonstrated in the Chaney-starring London After Midnight (1927). Sadly, Chaney died of cancer in 1930. Enter Lugosi.

Ill at ease with sound, Browning often deferred to cinematographer Karl Freund, whose credits included Fritz Lang's Metropolis(1927) (he would go on to direct The Mummy in 1932). Nevertheless, Browning achieved a pervasively creepy atmosphere with long periods of silence and stylised movement, massive, decayed staircases, dank dungeons, giant spider webs, squeaking bats, howling wolves, and Lugosi's tortured delivery ("Listen to them, children of the night. What music they make").

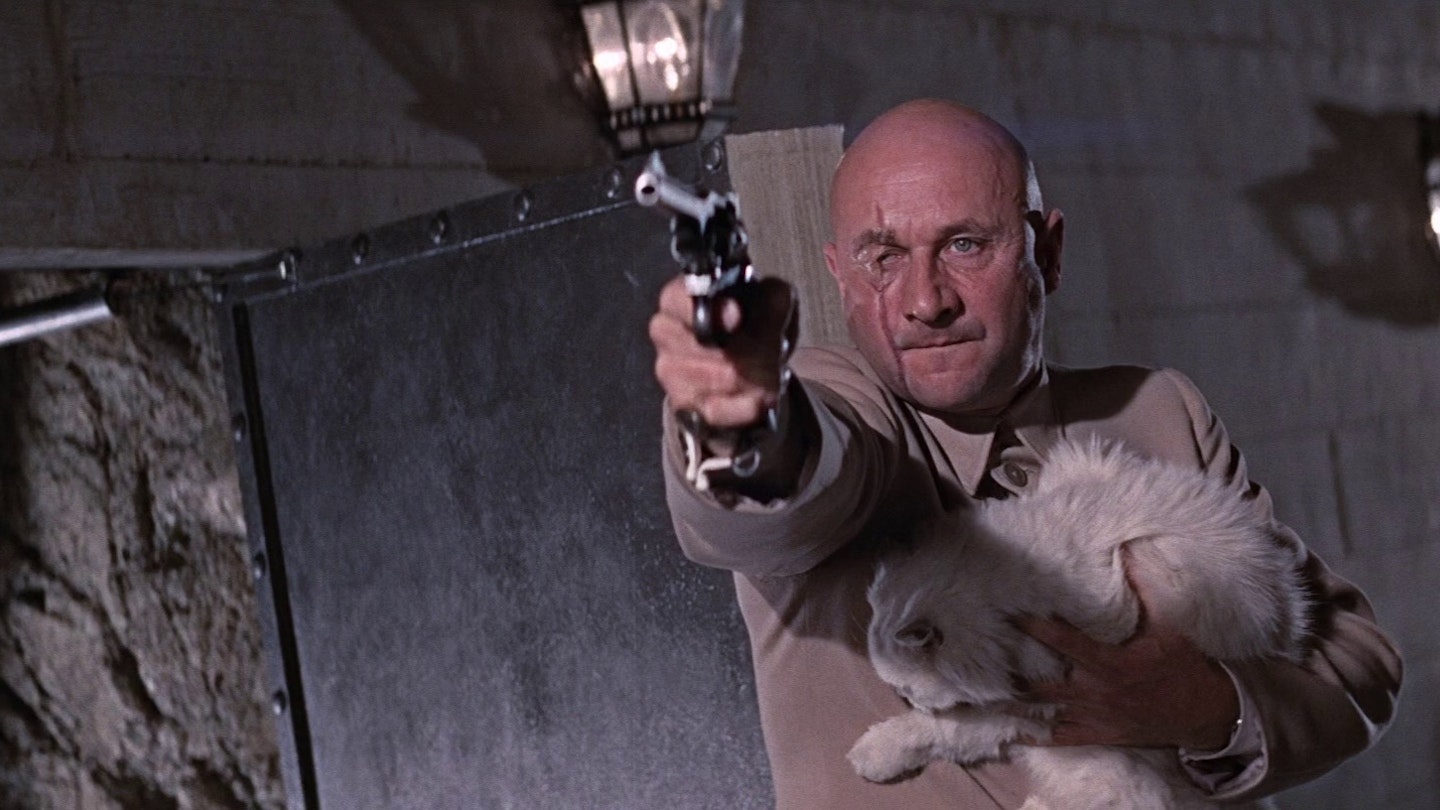

That it is Lugosi's presence that makes this film a classic is easy to demonstrate thanks to the early sound era practice of making different language versions of the same movie. Using the same script and sets, Universal produced a Spanish-speaking Dracula simultaneously, its cast and crew working through the night to make way for Browning's unit by day. In many ways it is technically superior, with more interesting, more fluid camera work. But its Dracula, Carlos Villarias, is as hokey as Lugosi but signally fails to create the deliriously tingling unease. Lugosi's unnaturalness is strangely perfect. He sported no fangs. He had no special effects make-up other than dark lipstick and light green greasepaint. Pencil spotlights were shone on his eyes to emphasise his hypnotic stare.

Later Draculas have always been determinedly un-Lugosi-like: tall, smooth Christopher Lee in Hammer's handsome cycle, Jack Palance's twisted victim figure, Frank Langella's rakish seducer, tortured Gary Oldman in Coppola's spectacle, Klaus Kinski sensationally disgusting in Herzog's remake of Nosferatu (1979). But from the Universal horror cycle through scores of derivative B-movies, parodies, remakes and spinoffs (including Sesame Street's numerate instructor The Count), it is the image of Lugosi that endures as the iconic vampire. So inseparable did he become from the role of Dracula that he ended up parodying the role in ever more degrading vehicles, the last and lowest being Ed Wood's notorious Plan 9 From Outer Space (1956).