The Room is a bad movie. No question. Whether or not it is officially The Worst Movie Of All Time is a matter of taste (countless films, from Sex Lives Of The Potato Men to Superman IV, could easily jostle for that crown of thorns), but cult status and midnight screenings have turned it into something else entirely: a latter-day Plan 9 From Outer Space, an icon of so-bad-it’s-good cinema, reaching beyond its meagre ambitions to become a timeless slice of outsider art. The question at its heart: how could a film so oddly incompetent ever exist in completed form?

Like *La La Land* for losers.

It’s a question The Disaster Artist certainly grapples with, faithfully adapting the memoir by The Room’s star and producer Greg Sestero. But what’s fascinating is how earnest the whole project is. The story of how the enigmatic writer-director-star Tommy Wiseau came to make The Room is certainly a farcical tale, but for all his blundering ineptitudes, he is treated here with remarkable respect.

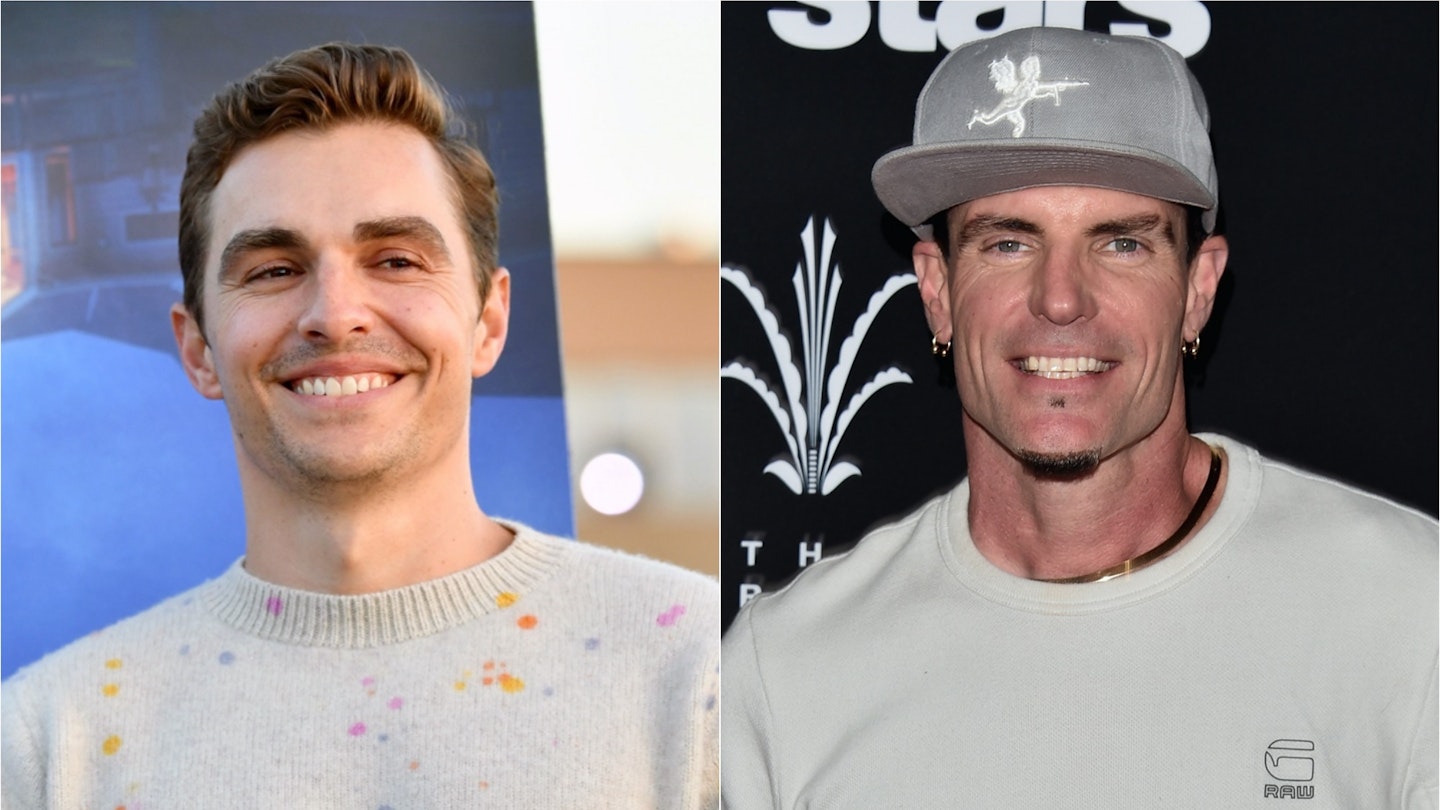

Wiseau (played here by James Franco, who also directs) is a gift of a character. Petulant, unpredictable, with the wardrobe of a garish pirate and the accent of an Eastern European with a frog in his throat, Franco’s Wiseau is a comedy masterclass in both understatement and overstatement, summoning a belly laugh from an over-the-top dramatic reading of Shakespeare just as easily as a quiet guttural "yah".

Wiseau’s eccentricities generate big laughs, as do the perfectly sweded recreations of The Room’s most infamous scenes. Wiseau had an inadvertent surrealist’s touch in his work: whether laughing inappropriately at a story about a woman being hospitalised, to inane scenes of ball-tossing, to the abrupt and jarring tones swerves between melodrama and broad light entertainment. These recreations — deployed with the accuracy of a master draughtsman, as the post-credits side-by-side demonstrate — reach a zenith in the final minutes, as we watch the glorious disaster of the film’s premiere, which captures the spirit of The Room’s always-lively midnight screenings. It’s a reminder that cinema-going is always a participatory event (even if spoon-throwing is unique to this case).

Franco allows himself the occasional snark, mostly through Sandy Schklair, the weary script supervisor played by Seth Rogen, hat-tipping the irony that the original film is usually viewed through. But elsewhere, it’s a surprisingly serious ode to the Quixotic chase of the Hollywood dream. It’s like La La Land for losers, where following your dream leads to failure and ridicule instead of romance and success.

The question, then, becomes “why?”, rather than “how?” What is it that drove Wiseau to continue, despite all evidence suggesting he should stop? One of the film’s competing themes is that Hollywood is full of dreamers who don’t deserve to be there, and there is an entitlement to him that is not uncommon among wannabes. “Just because you want it,” insists Judd Apatow in one of the film’s many cameos, “doesn’t mean it’s going to happen. It’s one in a million, even with Brando’s talent.”

Perhaps Wiseau realises his folly. As the shoot progresses, he takes on some of the industry’s more unpleasant traits: showing up late, treating his cast badly, engaging in shady accounting (it’s never explained how Wiseau funds the film, or where his fortune came from), and becoming stricken with toxic jealousy over Sestero, his more handsome, successful, reasonable friend.

Franco is interested in creative differences as much as creative inadequacies. If the film’s latter third perhaps loses some comedic lustre, it still manages to be an authentic exploration of the artistic process, and the burdens of collaboration. This is a film about how painful art can be, but suggests that the pain is worth it, even if everyone laughs at you. Ultimately, it’s a romantic hymn to the old-school crackle of moviemaking, giving even the most preposterous dreamers credence. “The worst day on a movie set,” observes Jacki Weaver’s long-suffering luvvie Carolyn, after fainting under the hot studio lights, “is better than the best day anywhere else.” Even with no discernible talent whatsoever, The Disaster Artist argues, there’s something pure and noble about chasing that rainbow.