Following the debacle of Tora! Tora! Tora! and the box-office failure of Dodes'kaden, Akira Kurosawa attempted suicide. Yet, he was ready to resume his career within a year and accepted funding from Mosfilm for this imposing adaptation of the memoirs of soldier-explorer Vladimir Arseniev. However, Arseniev's friendship with Dersu Uzala mattered less to Kurosawa than the opportunity to lament the unstoppable march of progress that was destroying areas of untouched wilderness and corrupting the peoples who had lived there undisturbed for centuries.

Kurosawa shot in 70mm to convey the vastness of the Siberian taiga. But the scale also served to detach the director from his subject and, while this is often an achingly beautiful and deeply moving film, it's not one of Kurosawa's more heartfelt efforts.

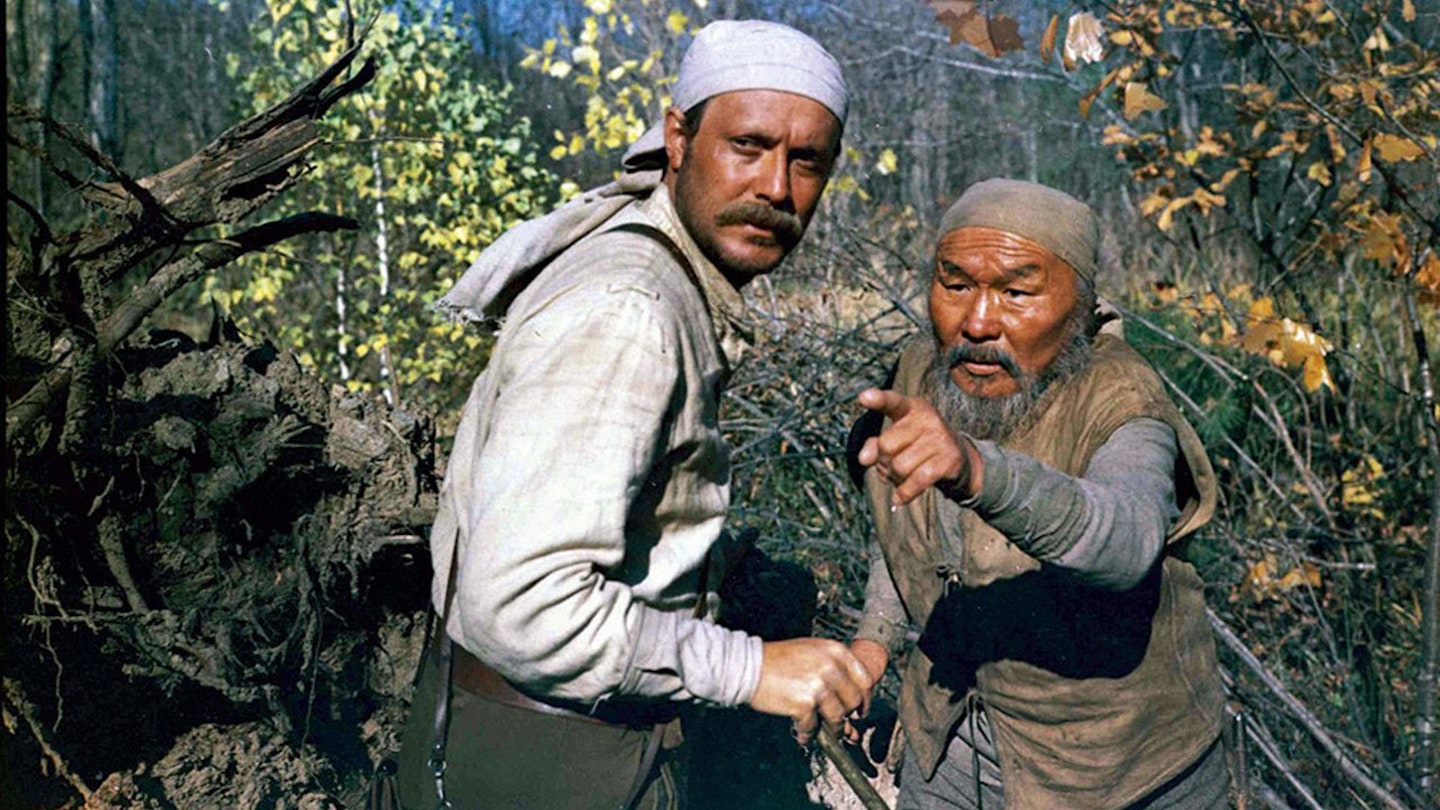

The Ussuri landscape is often idealised and Dersu's understanding of it is similarly romanticised. Indeed, there were critics who accused Kurosawa of patronising Dersu by presenting him as a latterday version of Rousseau's noble savage. Yet, he is clearly more akin to a Siberian samurai, whose code is rooted in respect for nature and co-existence with even menacing beasts, like tigers.

Conversely, Kurosawa's depiction of life in Khaboravsk is naively pessimistic, with domestic comforts and technical advances being considered equal evils with the claustrophobic enclosure and commercial exploitation of urban existence.

Compositionally, Kurosawa tends towards aloof pictorialism (note the use of telephoto lenses and the scarcity of close-ups). Yet his use of colour and light and the manner in which he binds his characters into their environment is masterly. What's more, there are also several memorable set-pieces, including the montages of the tree branches and the nocturnal cacophony, and the contrasting rescues, in which Dersu first saves Arseniev from the blizzard and then the Russians deliver Dersu from the rapids.

Five years later, Kurosawa would achieve a more complete fusion of theme and image in Kagemusha.