Jim Jarmusch is no stranger to visiting other worlds. In Dead Man, he went Western; in Ghost Dog: The Way Of The Samurai, he dabbled in Mob movies; in Only Lovers Left Alive, he hung out in a cool-as-fuck rock star vampire world. But whatever his flirtations with genre, every Jarmusch film remains recognisably Jarmuschian. The Dead Don’t Die follows that trend, blending his signature low-key style with some high-end genre affectations. But the tension between the two worlds is never quite resolved.

Which is not to say there’s not a huge amount to admire here, and the set-up is extremely strong. Like Richard Linklater or Kelly Reichardt, Jarmusch likes to simply plonk a camera in front of interesting, down-to-earth characters, and let them just shoot the shit. And that’s how the first act rumbles on, as we are slowly introduced to a quietly colourful array of simple everyday folk in a simple everyday town — named ‘Centerville’, to heavy-handedly emphasise just how simple and everyday it is.

Some of it feels recognisably politically incorrect for middle America, or really any insular community: we witness regulars at the local diner gossip about the “foreign woman” who’s just started working at the town morgue, while another character wears a Trumpian red baseball cap (with a decidedly more offensive slogan). Like much of his filmography, Jarmusch is content to spend some quality time with his characters, and the film’s early scenes show a subtlety of observation that perhaps doesn’t remain as the running time rolls on.

After an intriguing start, _The Dead Don’t Die_ plateaus.

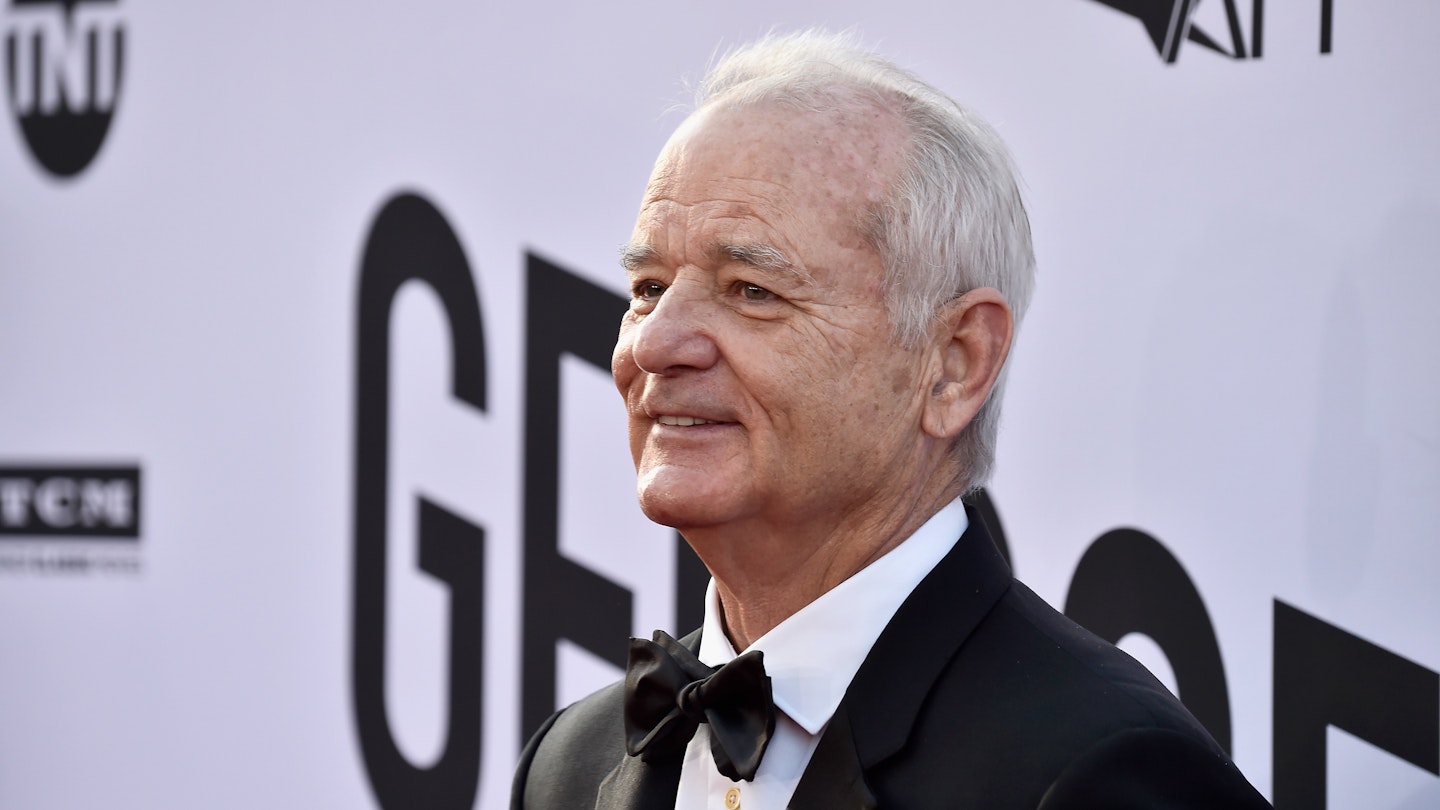

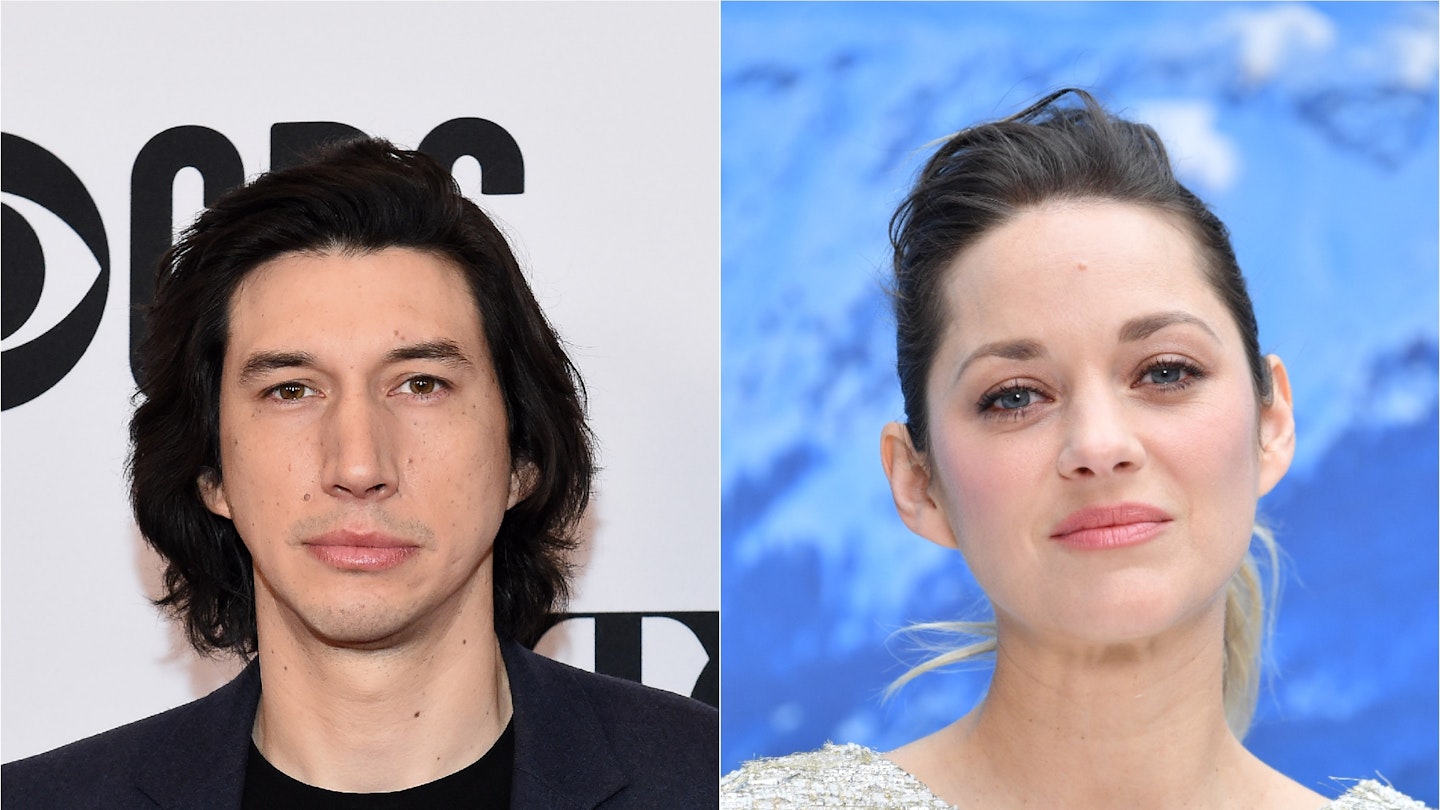

Guiding us through Centerville are two police officers, played by Bill Murray and Adam Driver, who take a relaxed approach to law enforcement and a serious approach to coffee and doughnuts. Murray and Driver are two of Jarmusch’s favourite muses — the De Niro and DiCaprio to his Scorsese, if you like — and few actors capture that lacksadasical sense of humour quite as well as them, both faces almost Buster Keaton-esque in their deadpan resolve. Through the pair we are introduced to a vast ensemble of supporting characters — effectively an entire cast of cameos. It’s hard to pick a favourite among so many gently glorious little turns, from Danny Glover’s essentially decent old store owner, to RZA’s cryptically wise delivery man, to Tom Waits’ hairy hermit, to Tilda Swinton’s Scottish samurai.

And for a little while, it feels like this could just be a freewheeling (if slightly off-kilter) portrait of small-town life, like a wackier version of Jarmusch’s previous film, Paterson. But something is rumbling in the background, and soon the foreground too; a hand reaching through the soil of a grave marks the moment the film reaches through into more formulaic genre territory.

Patience is always a virtue in a Jarmusch movie, of course; he is a master of slow cinema. But after such an intriguing start, The Dead Don’t Die plateaus, dramatically, comedically and frightfully. George Romero is referenced, both directly and indirectly, from the grave-reaching hand onwards. But the genre has moved on since Romero’s 1970s heyday. Zombies no longer hold the power they once had; they need something more than moaning and stumbling. Even the zombie comedy is no longer novel, with the likes of Shaun Of The Dead and Zombieland offering witty, cine-literate takes on the template. It’s not clear what fresh ideas The Dead Don’t Die can offer here.

Much of its in-universe rules are borrowed directly from Romero: like 1978’s Dawn Of The Dead, these ghouls are all obsessed with the one thing they desired as living beings. Here it’s given a rather first-base 21st-century spin, the zombies wailing about WiFi and Bluetooth, which feels like an overly didactic Black Mirror first draft. Zombies have always been a useful parable, an allegory in which to feed on the brains of modern society, and the stuff about a dying Earth certainly feels more prescient. But what is Jarmusch really trying to say about capitalism that Romero didn’t already say in 1968?

There are other problems with the film elsewhere: some audacious swings into meta-comedy feel overly smug, while one particular character reveal is so bonkers and out-of-place that you wonder why it wasn’t left on the cutting room floor. But in spite of itself, The Dead Don’t Die remains a Jarmusch joint, to the end. It’s still a disarming world to hang out in; you just wish it could have been a little less indulgent