With Darkest Hour, director Joe Wright takes history at its most momentous, wraps it around a figure who couldn’t be more potently iconic, and places this rich but heavy package almost entirely in the hands of his leading man, Gary Oldman. An actor who, despite impressing us for decades with his chameleonic aptitude and emotive heft, has astonishingly been rewarded with only a single Oscar nomination (for Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, in 2012). If this film can’t change that, nothing will. It is truly a gift of a role, and Oldman repays Wright with the performance of a lifetime.

Complemented rather than smothered by make-up artist Kazuhiro Tsuji’s jowly prosthetics, Oldman revels in the high-volume bombast and tactless bluster of a PM who was thought an embarrassment by many of his peers. He barrels around Westminster on surprisingly light feet, like a low-flying, alcohol-fuelled dirigible with a cigar at its prow. He’ll dictate to his secretary Elizabeth Layton (James) amid the sploshes of bath-time before suddenly announcing his emergence “in a state of nature”, and spends so much time making life-or-death decisions in the loo, the WC on the door may as well be his initials.

It’s a timely reminder that world leaders should pause, absorb critique and question themselves.

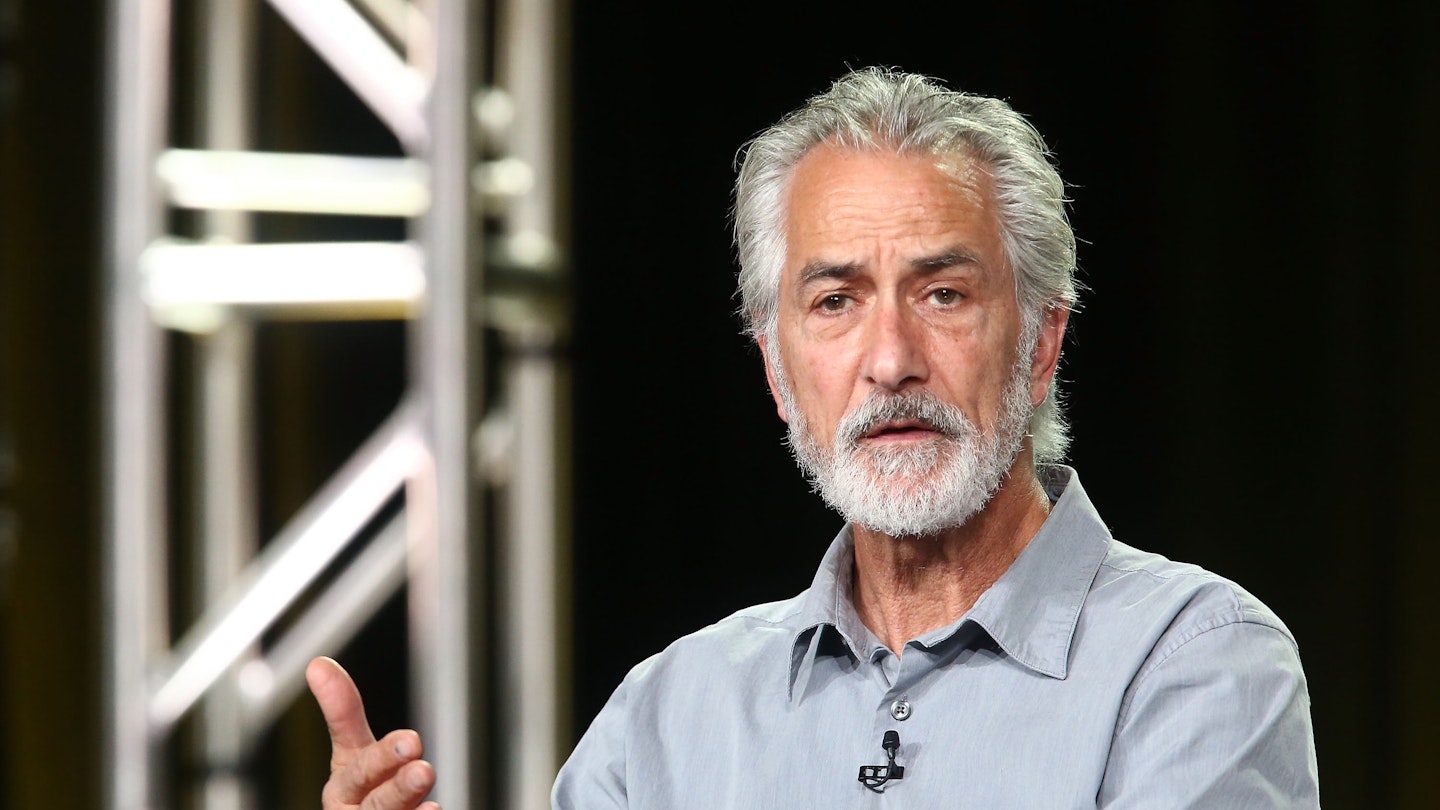

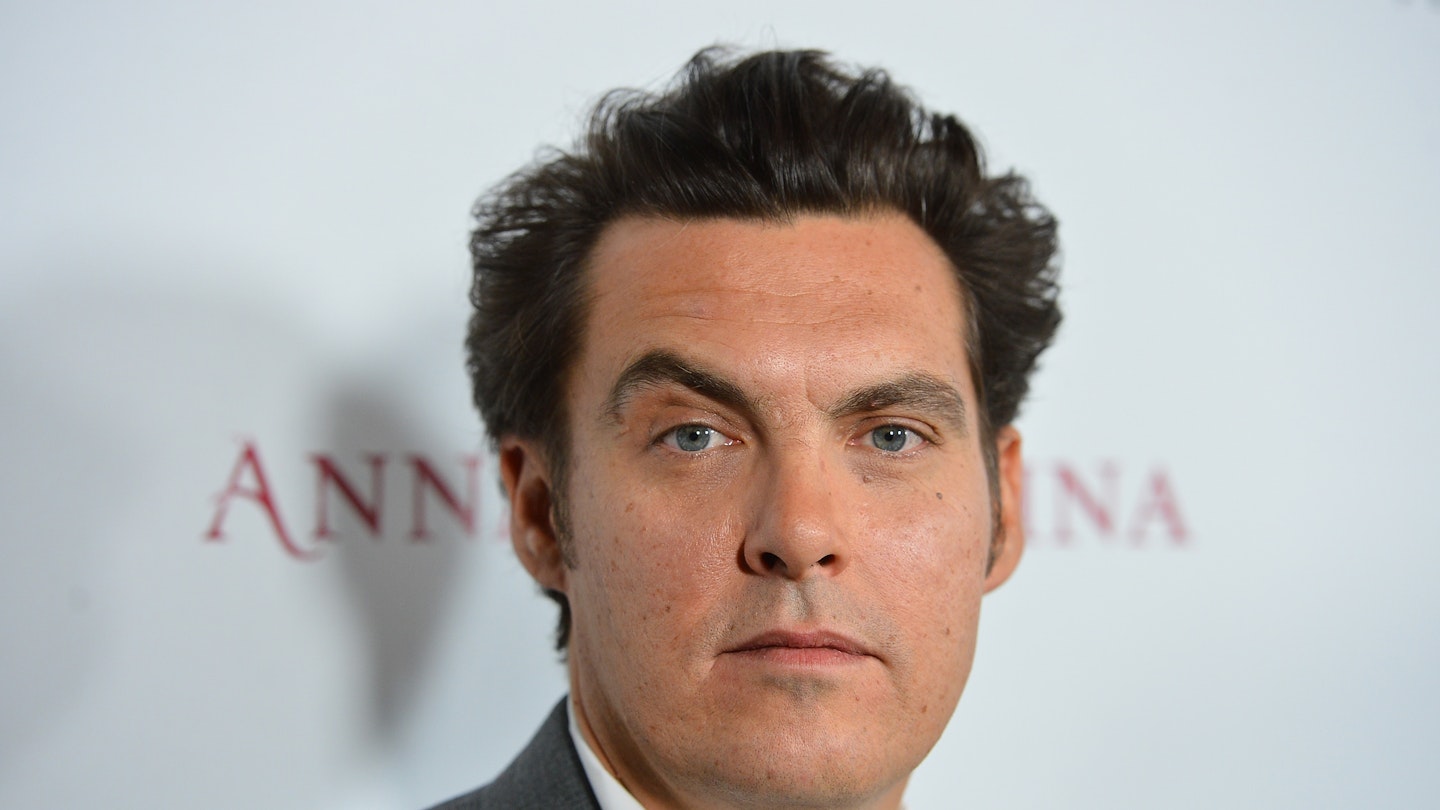

But Oldman also sinks deeply and empathically into Churchill’s lower ebbs, projecting a sagging, load-bearing frailty and eloquence-sapping indecision we less readily associate with this semi-mythical figure. As foreign secretary Viscount Halifax (Dillane, once more compelling as a grey, rigid man of power) politically manoeuvres against him, we see Churchill flag and flounder. Not only is it impressive evidence of Oldman’s dynamism and flexibility as an actor, it’s also a timely reminder that world leaders should pause, absorb critique and question themselves.

This isn’t a one-man show, though. Scott-Thomas — as Winston’s better, sharper half Clementine — and James are impressive, if rather peripheral in a script (by Anthony ‘The Theory Of Everything’ McCarten) which struggles to integrate its female participants into male-dominated ’40s Westminster, while Ben Mendelsohn more than holds his own opposite Oldman as the Winston-doubting King George.

Wright himself should be applauded, too, for imbuing this verbose, interior-rooted narrative with such visual flair. Britain’s halls of power are lit in a gorgeously noirish style, while one remarkable motif sees Churchill repeatedly boxed in by literal ink-black darkness, whether in a void-ascending lift or framed by the leaded glass of a closed door. Of course, Wright is returning to previously visited territory with Darkest Hour,. After all, 2007’s Atonement covered the same period and shared a climactic event: the evacuation from Dunkirk. Keen not to repeat himself (or, indeed, Christopher Nolan), Wright keeps the scenes of conflict mostly distant, merely an epic sideshow to the story’s true conflict: between Winston Churchill and his own conscience. Every moment of which is a joy to behold. If Oldman doesn’t get to flick a V on Oscar night, we’ll eat our Homburg hat.

.jpg?ar=16%3A9&fit=crop&crop=top&auto=format&w=1440&q=80)