Having flogged Jane Austen, the Brontes and Dickens to death in recent years, it is apparently time for litpic dramatists to recycle Dame Daphne du Maurier’s oeuvre again. In theory, this is fine by us. Daph spun plenty of great, screen-friendly yarns (including Rebecca, Jamaica Inn, The Birds and Don’t Look Now). She also had a dark imagination and she was notable for refusing to resolve her stories with neat endings or explanations. The mystery is paramount, and preferably insoluble, so that one goes away from it debating, conflicted, even haunted. This one has all the ingredients for a heady Gothic romantic thriller: the remote Cornish manor, the handsome, wealthy young hero, the enigmatic, beauteous anti-heroine and plenty of suspense, with colour added by sour, smartarse manservants, poor (but jolly) peasants and simpering spinsters eyeing the hero hungrily across the dinner table.

Handsomely done but short on the atmosphere and passion of a genre classic.

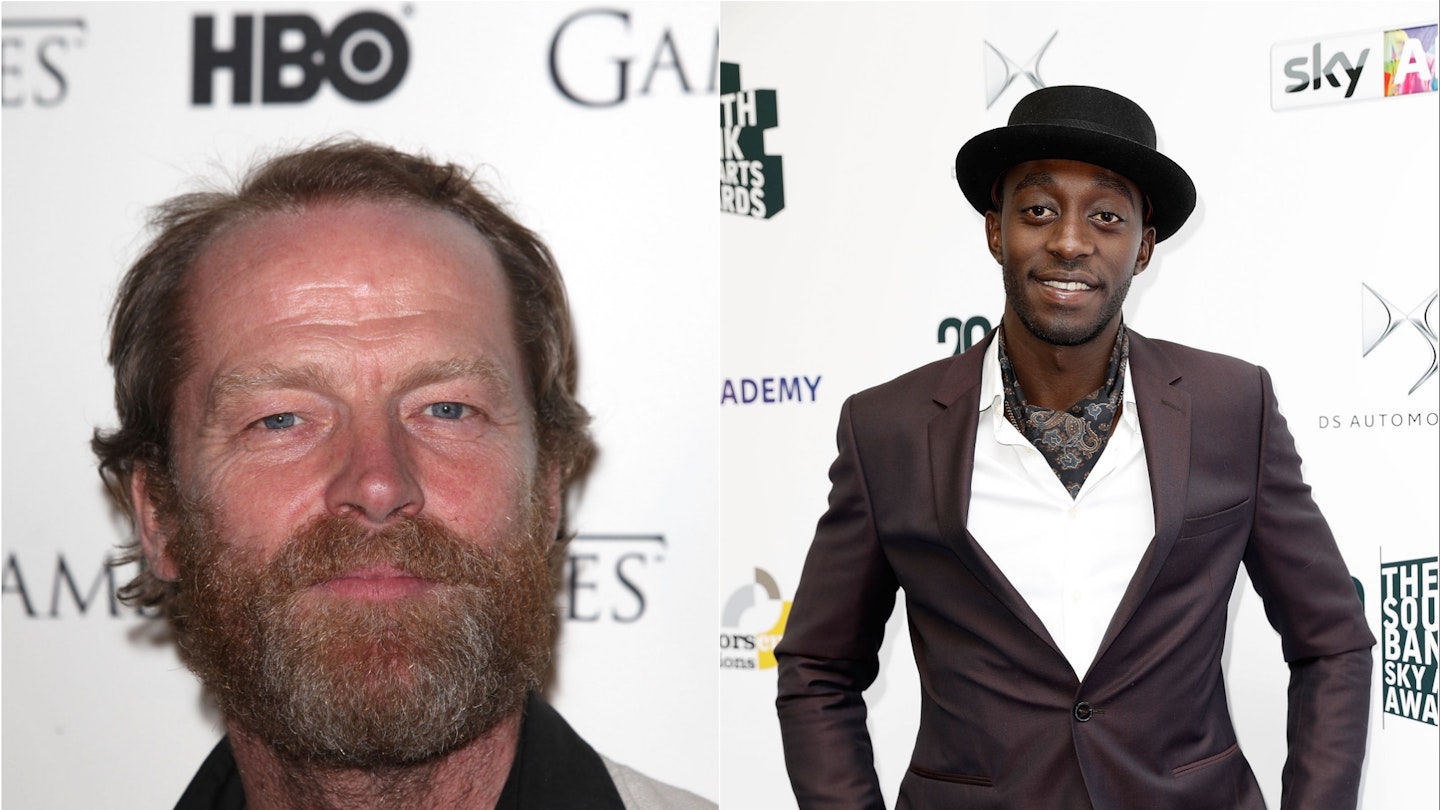

Sam Claflin gallops along cliffs in his becoming tight breeches brooding like he’s auditioning for Poldark. Rachel Weisz wafts fragrantly in veils and beautifully fitted widow’s weeds. Holliday Grainger is first-rate as Louise, the pretty childhood friend and neighbour with an unrequited yen for Philip who stirs things up, and an agreeable quota of veteran thespians (Iain Glenn as Philip’s godfather, Simon Russell Beale as his lawyer) do their stuff nicely. What’s not to like? Weisz is particularly well cast, lovely and beguiling but also with the ability to suggest charm, vulnerability, distaste or devious calculation by the subtlest fleeting nuances.

Those familiar with du Maurier’s novel and/or the 1952 film version (for which a very young, gorgeous Richard Burton, making his Hollywood debut, received his first Academy Award nomination opposite a miscast Olivia de Havilland) will be struck by some intriguing new aspects. Claflin’s Philip is an immature pup who — having been taken in as an orphaned tot by wonderful Cousin Ambrose (also played by Claflin) and raised in a world almost entirely absent of women — scarcely knows what to do with a sophisticate like Rachel and develops a distinctly rash, unattractively possessive obsession with her. While we rightly view with suspicious alarm Rachel brewing her unpalatable herbal tisanes (or “twig soup” as the doddering manservant nicely puts it) “specially for Philip”, she emerges rather startlingly — and anachronistically — as a woman who may have a scandalous past and a self-serving agenda but an urgent need for independence, freedom and her rights.

Amid these wrinkles, the key questions – is she or isn’t she a Black Widow? did she or didn’t she poison Ambrose? is she or isn’t she playing Philip for a fool? how far is she prepared to go to get his inheritance? – almost fade in our exasperation with the emphasis on Philip’s dangerously naive adolescent moods and demands. It is almost entirely thanks to Weisz, deftly mercurial, that any suspense is maintained. Happily screenwriter-director Roger Michell, who has had his own ups (Le Week-End) and downs (Hyde Park On Hudson) keeps her almost as determinedly unknowable as du Maurier intended, so that, the way it plays out, she is destined to remain for Philip, as she was to Ambrose, “Rachel, my torment”.