Depending on your take, the Coens have been off their game, under par, or basically crap of late. Of course, the devotee (easy to spot: goateed, bespectacled, Little Lebowski Urban Achievers T-shirt) might posit some notion where they were deliberately sabotaging their own reputation in some advanced form of self-mockery. Who knows? It remains tough to argue that Intolerable Cruelty and The Ladykillers are of the same calibre as the preceding nine straight wacko-treasures (yes, including Hudsucker) that sealed their glowing rep as the hippest geeks around.

Well, this fresh in: whatever mosquito was buzzing in their ears is now a small red stain on the flock wallpaper. The Coens have rediscovered their mojo, with, dare we say it, a new maturity. There is also something back-to-basics about No Country For Old Men, adapted from Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Cormac McCarthy’s violent neo-Western. It’s got Blood Simple’s dark moves, that clammy sense of death lurking in the barren Texan landscape. And being a knotted tale of crime innately wrapped up in an imposing location, it shares DNA with Fargo and Miller’s Crossing.

What surprises is how the film remains both recognisably McCarthy’s terse and sorrowful parable, and a Coens enterprise bathed in oil-black humour. Despite the fact that the brothers lift much of the dialogue verbatim from the page, in the mouths of their cast the lines sound like choice Coenisms: all jazzy syncopations or deadpan comebacks. “If I don’t come back, tell my mother I love her,” Josh Brolin’s sort-of hero Llewellyn Moss tells his wary

but perceptive wife Carla Jean (Kelly Macdonald) before he heads into the mouth of trouble. “Your mother’s dead,” she retorts. “Then I’ll tell her myself,” he sighs.

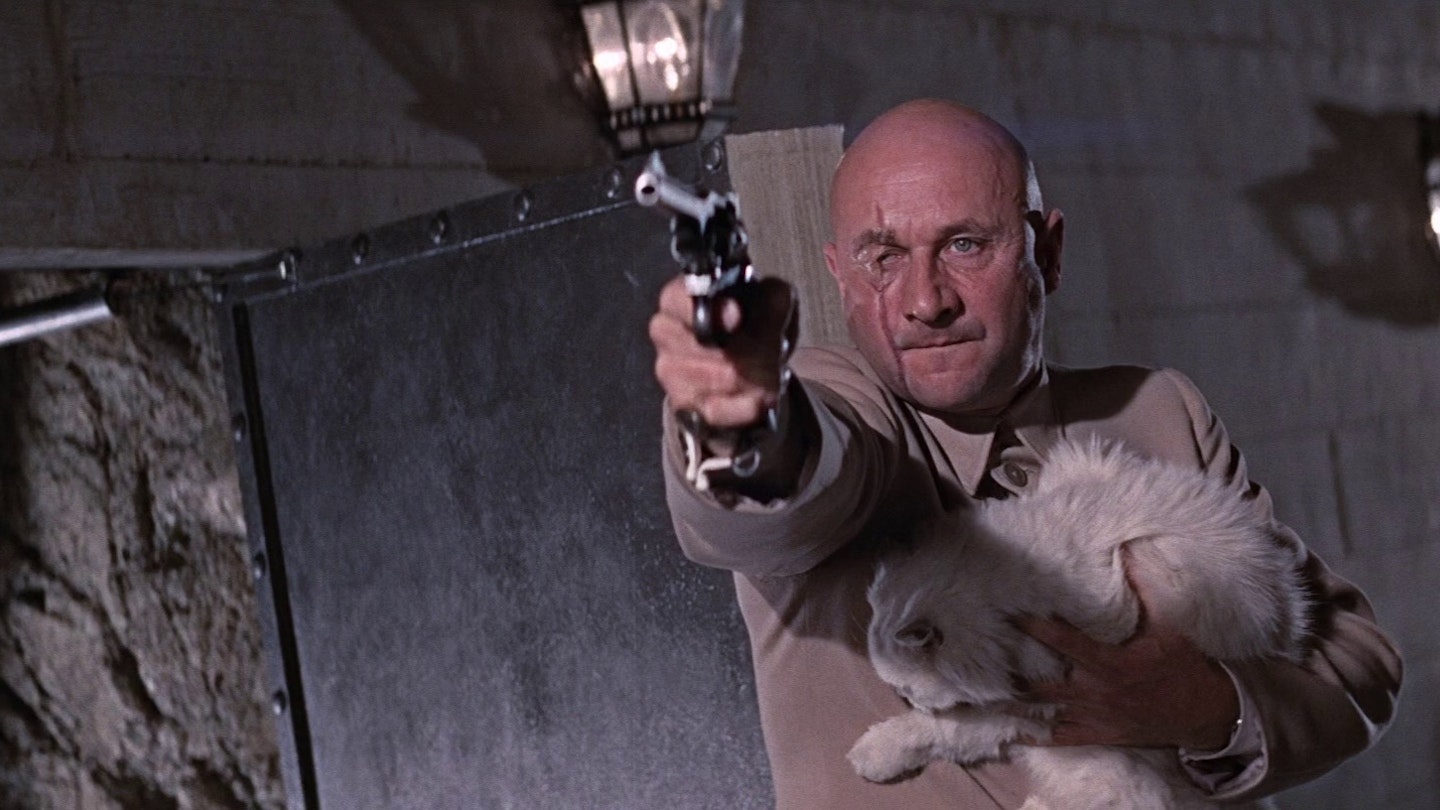

The plot is triple-headed, with the narrative shifting focus whenever one of the leads seems to be taking centre stage. We start eyeing the tremulous determination of Moss, a local hunter who happens upon the remains of a drug deal gone badly wrong. Cadavers cook in the desert sun, even a dead dog, and a trail of blood, splattered like ink along the parched ground, leads Moss to a case containing two million dollars. He elects, as all noir folk are supposed to, to take the money and run. Bad move considering the clean-up guy is Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), a killer with the implacable dedication of a Terminator and the domed haircut of a psychopathic Monkee. What proceeds is a startling chase movie scattering through the border towns, grimy motels, and dry gulches of West Texas. Always two steps behind is the old man of the tale, Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), a lawman longing for retirement, facing an evil that he can no longer decipher. This is a new crew for the brothers to play with. Jones is a perfect fit for the weatherworn Bell: he is Texan to his core, and looks as if he is entirely the product of McCarthy’s Biblical prose. Age has granted him stillness as a performer, and he gives the movie a grace above its lashing violence. Brolin, battered from pillar to post, is the strong, doomed heart of the story. But Bardem’s is the role with flamboyant possibilities — a stone-cold killer obsessed with chance, holding lives to the random toss of a quarter. He is the embodiment of evil as blank force made breathtakingly plausible. With his Spanish accent flattened, his voice seems to come from a place not wholly human.

Those who find the Coens’ smarty-pants routines insufferable will find relief in the naturalism on show. This is not a world fastened beneath the hermetic seal of their whirligig genre-bending, but one that lives and breathes and bleeds. There is something resonant in Bell’s soulful philosophy, something tender in Moss’ love of his wife.

And we still get all the off-centre mannerisms that made the brothers so much fun to begin with. Although, silence is a tool we’ve not encountered before. Sure, Billy Bob Thornton barely uttered a syllable in The Man Who Wasn’t There, but we had his interior drawl. Here, between the bursts of visceral action, the film hangs on a terrifying soundlessness and the striking atonal power of sharp noises against nothingness: a bulb being unscrewed, a footfall on a wooden floor, the soft breath of wind over hardscrabble terrain. Even Carter Burwell’s score is defined by its imperceptibility — made up only of low groans and eerie whistles.

If the final act strikes out against formula to downplay rather than crescendo, it is true to the book. The simple satisfaction of traditional showdowns is evaded for a lyrical note that strikes both as deeply pessimistic and strangely pure. There is something of Miller’s Crossing’s noble farewell about it. Those brothers from another planet have returned to Earth.