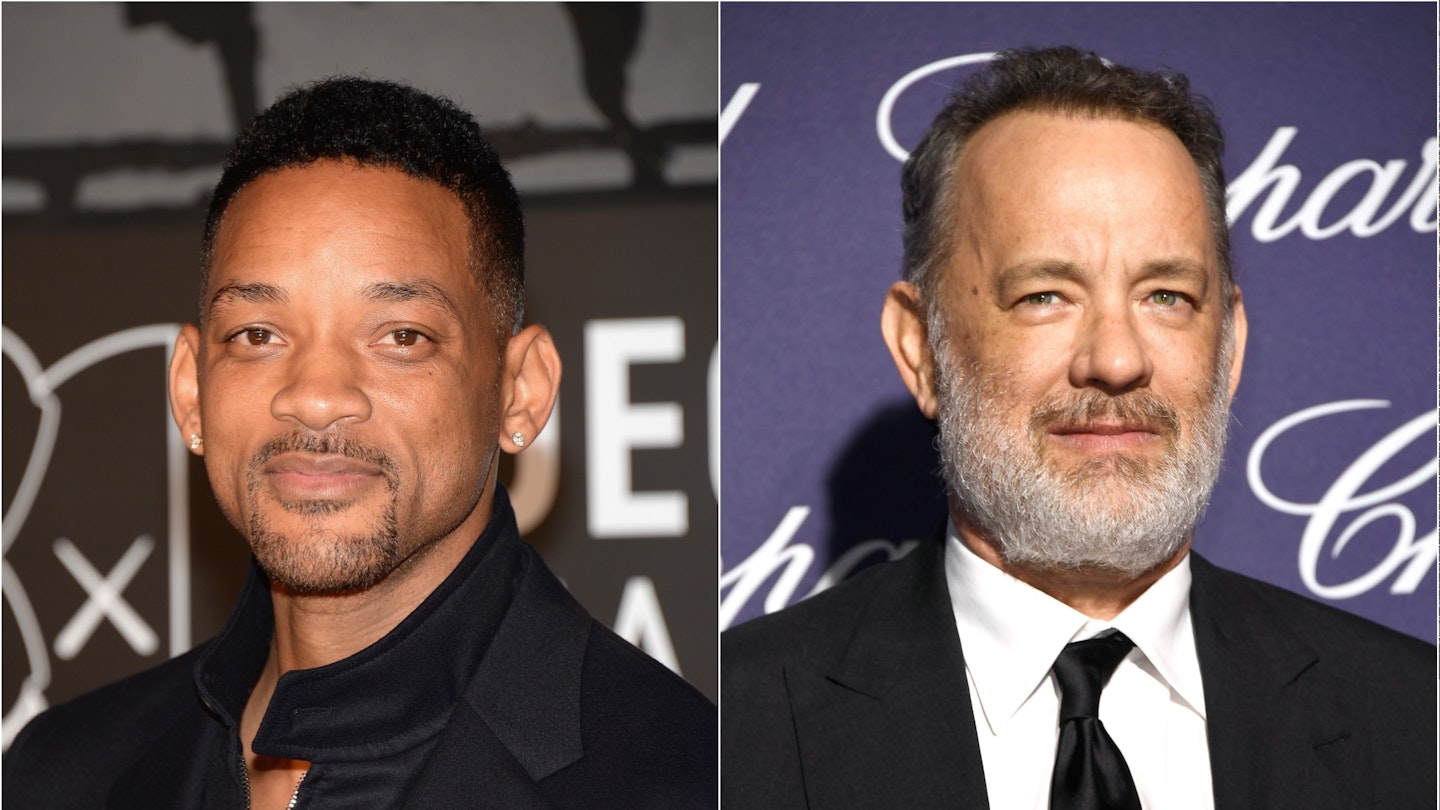

If you subtracted the A-list stars (say, swap Will Smith for Steve Guttenberg) and big-budget studio sheen, Collateral Beauty might feel at home on Channel 5 around 3pm. Played out in a twinkly New York, its high-concept idea — a grieving man is taught life lessons by incarnations of Death, Time and Love — and penchant for greeting-card sentiments suggests a tale of schmaltz that would play perfectly in a pre-Neighbours slot. Yet David Frankel’s film never really hits the broad emotional spots (let alone the nuanced ones), partly because it trades in a glossy sense of the solemn and partly because it never creates a story world that unifies its mixture of Dickensian fantasy, bereavement drama, soap opera and New York life. It’s slick, with a smattering of decent performances, but ultimately undone by sledgehammer levels of subtlety.

The movie is at its most engaging in its opening stretch, when playing out its scam of three actors embodying notions of Love (Knightley), Time (Latimore) and Death (Mirren) to force grieving ad exec Howard Inlet (Smith) into feeling something. This is intercut with Howard’s stuttering attempts to join a bereavement group, led by Madeleine (a warm, appealing Harris). As Howard’s story moves on, Allan Loeb’s screenplay mechanically uses the Madeleine storyline as a yardstick to measure how the three abstracts are bringing him back to life. How these two storylines ultimately coalesce is both the film’s biggest reveal and dampest squib.

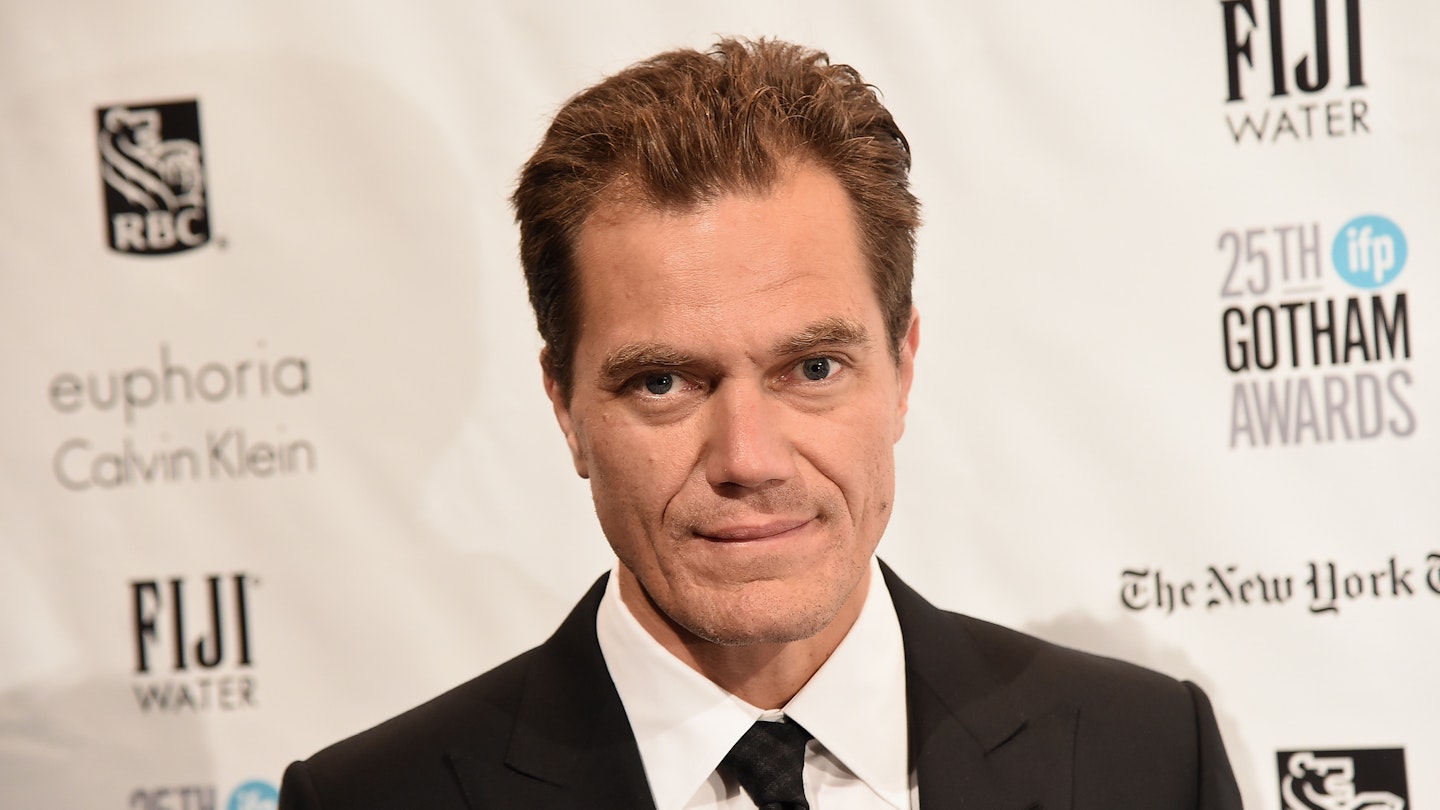

If it is not enough that the three muses attempt to ‘cure’ Howard, they are also working to rejuvenate the lives of their paymasters. Norton’s Whit is struggling to connect with his daughter (like all modern NY dads, he offers to buy her tickets to Hamilton) after an extra-marital affair — so he gets to spend time with Love; Peña’s Simon is dying of a terminal disease he won’t divulge to his family — so he is forced to confront Death; Winslet’s Claire has given up a chance at children and family life in favour of work (we only know this because she endlessly looks at adoption websites) — so she hangs out with Time. It’s programmatic and heavy-handed stuff, enlivened by the likes of Norton (who shares good chemistry with Knightley), Winslet and Peña.

Frankel, capable of the sublime (The Devil Wears Prada), the cutesie (Marley & Me) and the forgettable (The Big Year), offers touches of confident craft (each of the abstracts emerges out of beautiful soft focus) amid Domino-Toppling Symbolism. The quality supporting cast add colours to thin characters and cod philosophy (“Time is a stubborn illusion”): best in show is Mirren who, especially early on, has fun as a true thesp, citing acting guru Stella Adler and worrying about her reviews from Howard.

If the opening scene of Howard rallying his troops is pure Hitch, the rest of the movie is Smith in Seven Pounds miserablist mode. He is somnolent through the entire movie, never really suggesting Howard’s inner life or anguish. Taken alongside A New York’s Winter’s Tale, Smith clearly has a jones to make a heartwarming NYC tale. On this evidence, it’s a shame he has little idea how to deliver it.