Chicago is no Moulin Rouge. Okay, so perhaps that's slightly unfair. Not every musical post-MR is going to reinvent the wheel, and Chicago - the first out of the blocks - sure as hell doesn't. But it is rousing, sassy and hugely entertaining - and that ought to be enough to ensure that musicals stick around for a while yet.

A film version of Chicago has been almost inevitable since the show - which was originally directed by Bob Fosse in 1975 - was revived recently on Broadway and in the West End, and it's easy to see why. Every musical ultimately lives and dies by the quality of its songs, and there Chicago holds all the aces. A pure musical, in that there's a song practically every two or three minutes (indeed, the acerbic dialogue scenes are almost rushed through with indecent haste), Chicago is packed with great tunes, from the opening All That Jazz, to All I Care About Is Love, to John C. Reilly's plaintive Mr. Cellophane. Each of these subtly expands upon the movie's preoccupations with the American justice system (where celebrity talks and bullshit walks), female empowerment and the fickle nature of stardom, without beating you over the head. That, for the most part, they're toe-tapping classics, doesn't hurt either.

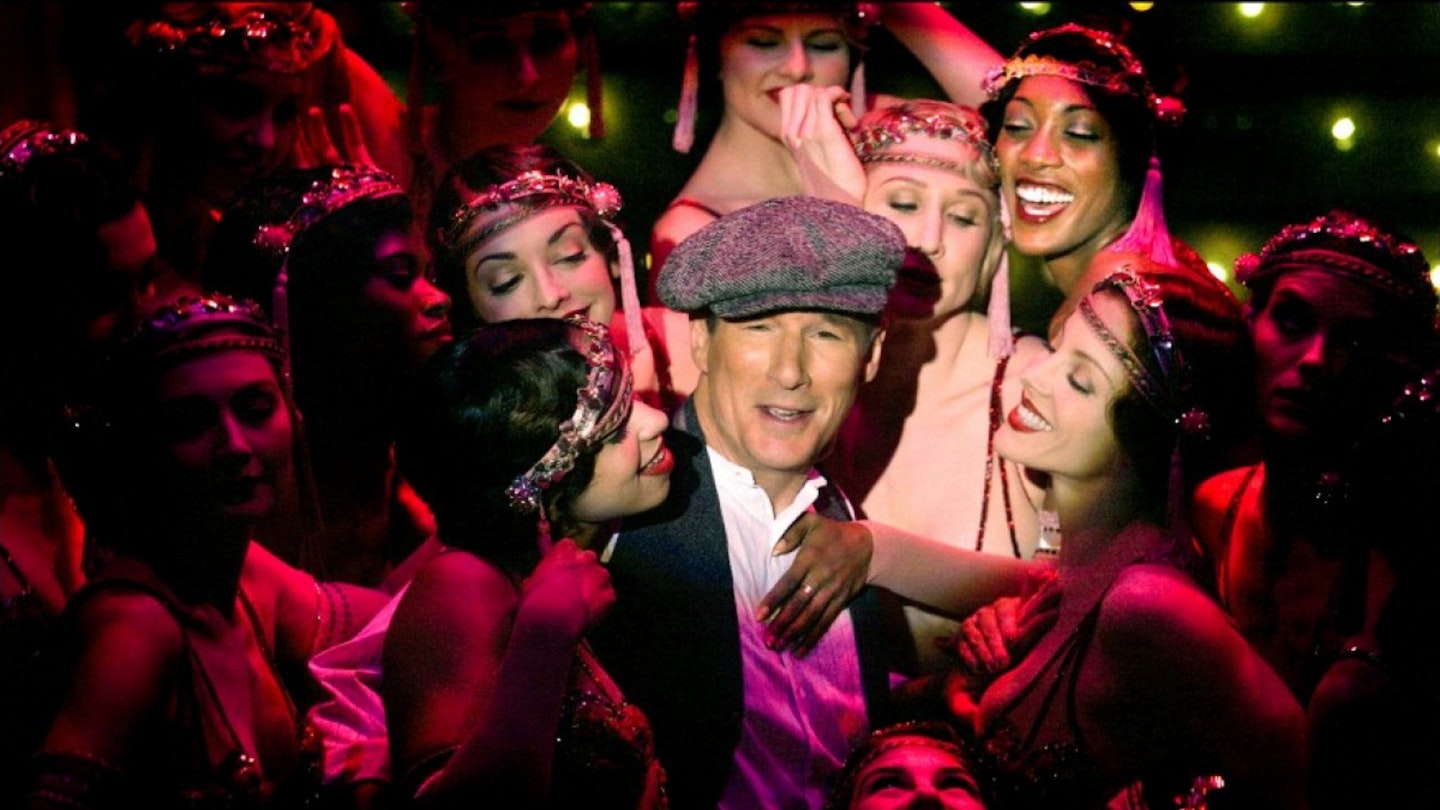

Yet good songs demand a good cast. At first glance, Chicago's experimental line-up doesn't bode well. Happy to report, though, everyone acquits themselves in style. The guys - Gere, very funny as the impossibly suave lawyer; and John C. Reilly, breaking hearts as Roxie's put-upon husband ' croon with the best of them, but this is all about the original Spice Girls, Roxie and Velma. Catherine and Renée.

Zeta-Jones may have started out in the West End, but the singing and dancing skills she unveils are still surprising, strutting her stuff with the confidence of a woman who knows that she's now Hollywood royalty. Her man-eating Velma fair burns up the screen, and to live with that Zellweger - very much the unproven Nicole Kidman of the equation - needs to be on her game. Thankfully, she is. Although lacking the raw sexuality you might expect of Roxie, Zellweger instead concentrates on the character's vulnerability, using her little girl lost voice to great effect. And yes, she can belt out a tune, her singing voice stronger than you might expect.

Overall, there are problems, of course: it's far too stagey, and for a film where the female cast spend 90 per cent of their time in bras and knickers, it's strangely unsexy. But it's first-timer Marshall who threatens to derail proceedings, his TV background manifesting itself in his addiction to stifling close-ups, uninventive camerawork and a strange adherence to the choreography of the stage show. He does try to open out the play Dennis Potter-style, but where a bolder director might have slowly merged the fantasy and reality worlds, Marshall's frenzied intercutting rapidly loses impact. Yet armed with that cast, those songs, and a budget large enough to recall glorious Technicolor MGM memories, even Ken Loach could make this fly. And Marshall is savvy enough to ensure this is a lavishly-mounted high time, just waiting to be had.