For those who scarcely recognise the version of West London propagated by Four Weddings and Notting Hill, writer/director/actor Noel Clarke’s sketch of the dangerous streets humming with violence, just alongside those townhouses with the bright doors, has long offered a hyperreal contrast. Now, a decade on from first film Kidulthood, not only has the world changed, but so has the man behind it. And yet, as Clarke reveals in this, the third and final part of the trilogy (helpfully hashtagged #theend), the years may pass and the world may change, but that doesn’t prevent your life spinning backwards in the blink of an eye.

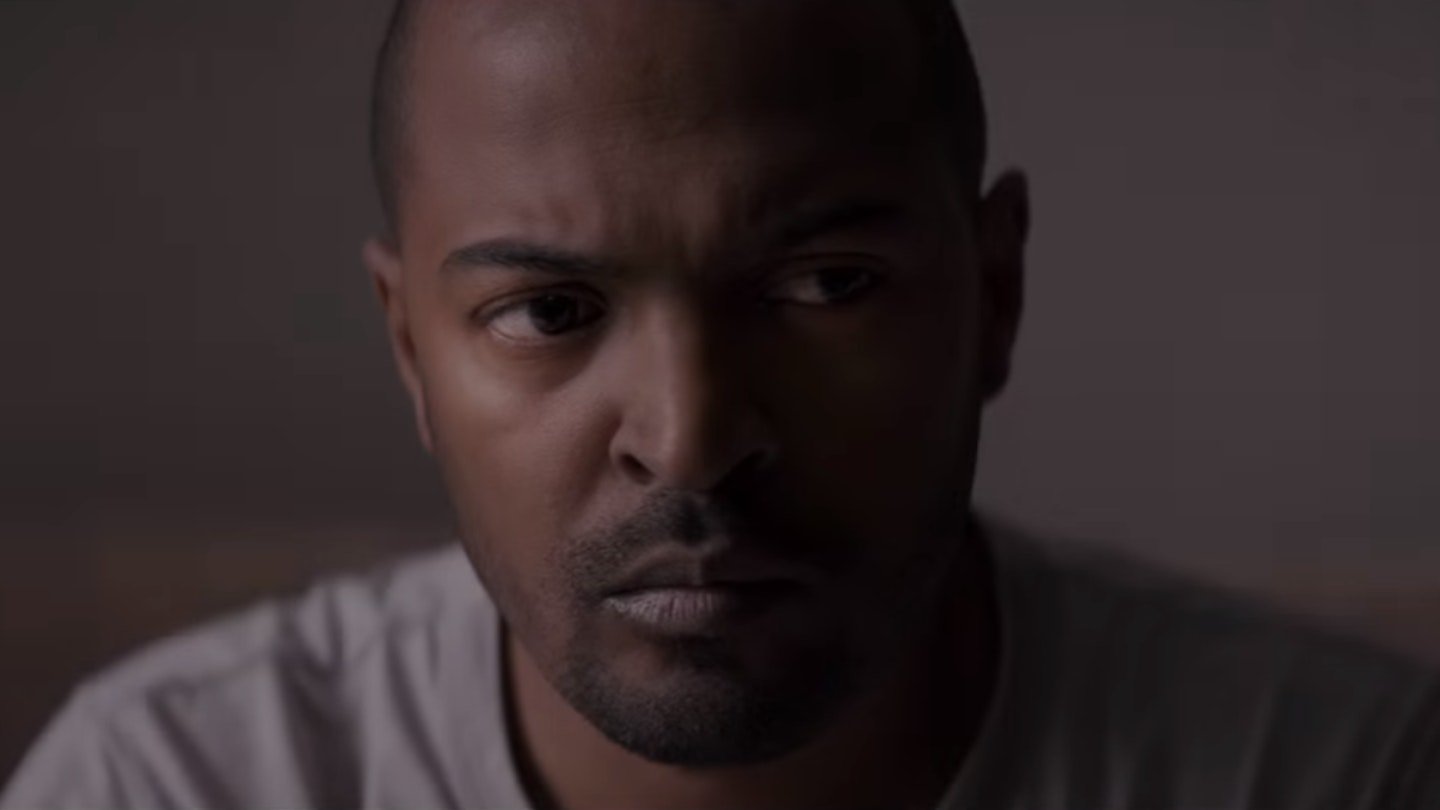

Clarke’s Sam Peel, who we last saw in Adulthood surviving many, many attempts on his life after coming out of prison for murder, is now older, heavier and unfortunately (you suspect) not completely wiser. And his house, four jobs, lawyer girlfriend Kayla (Warren-Markland) and, most significantly, two kids, aren’t enough to save him from being pulled into the underworld when his family are threatened and his brother is shot in the opening sequence. “The only person more dangerous than someone with nothing to lose is someone who stands to lose everything,” says Sam of this trigger for the return of the hoodie and the man he used to be (and perhaps, still is).

Clarke refuses to whitewash the realities of working-class inner city life, even if it is difficult for us to watch.

As with the previous two films, the violence is graphic and the representation of women ugly — 90 per cent of them are abused, dismissed, belittled, brutalised, and/or referred to as “slags”. But, while it ain’t pretty, arguably this is the power and potency of Clarke’s films. He refuses to whitewash the realities of working-class inner city life on the streets of West London, even if it is difficult for us to watch.

Balance, though, comes in two forms: firstly, the characters of Kayla and quick-mouthed young hood Poppy (Rosa Coduri), both demanding respect amidst the self-sabotage and insecurity-induced misogyny they encounter. And secondly, and most brilliantly, dark and supremely daft humour — often where you least expect it (including a thread about a Sainsbury’s discount card that serves as a pretty beautiful metaphor for the tension between old and new realities). Leading the charge on this front — and stealing much of the film from under Clarke’s nose — is Henry (Arnold Oceng), reluctant sidekick in Sam’s descent into the underworld, who drives a Toyota Prius, makes jewellery with his wife and tells a group of new kids on the street to “back it up before I heat it up” while holding his son’s action figure as a fake gun.

There are missteps, however; miscalculations which undercut the necessary tension just as it reaches fever pitch. Jason Maza — part Gal Dove, part Tommy DeVito — plays gangland boss Daley on a knife edge of absurdity (staying the right side of it in the main), but returning bad guy Uncle Curtis (Cornell John) lurches too willingly from menace into melodrama. And Clarke can’t avoid employing the third-in-a-trilogy tropes: one last job/reformed guy helps new guy who is essentially him/grossly unfair family tragedy as his three-parter reaches its too-neat conclusion.

But perhaps that was inevitable.