Given that Arthur Penn's gorgeously-photographed, ecstatically bloody folk tale hit the screens in an era when the

depression-era chic. Most significantly though, Newsweek critic Joseph Morgenstern took the unprecedented step of admitting that his original review was completely wrong and publishing a revised version praising the film to the skies.

In the end, Bonnie And Clyde re-opened. It became one of Warner Brothers biggest ever money-spinners and earned itself 10 Oscar nominations (it won two: Estelle Parsons for Best Supporting Actress and Burnett Guffey for Best Cinematography). In the process, of course, it turned the entire American movie industry on its head.

Naturally, the violence in Bonnie And Clyde was a sizeable bone of contention. But what really divided audiences was its moral ambiguity — its glamorising of two vicious killers and the easy manner in which it blended slapstick humour, overt eroticism and vivid bloodletting.

To the section of society that had choked on its collective martini over Guess Who's Coming To Dinner, it was the final nail in the coffin of common decency. To another, busy tuning in, turning in and dropping out, the anti-establishment image of two outlaw lovers on the run struck a resounding chord. The scene in which a cocksure Clyde offers his gun to a poor black sharecropper so he can shoot holes in the foreclosure sign erected by the bank that has evicted him, encapsulates the mood of the film perfectly. The criminal-as-folk-hero has been a theme intrinsic to American cinema ever since, and the Barrow gang's whole, dizzy crime spree is a defiant finger to the forces of law and order.

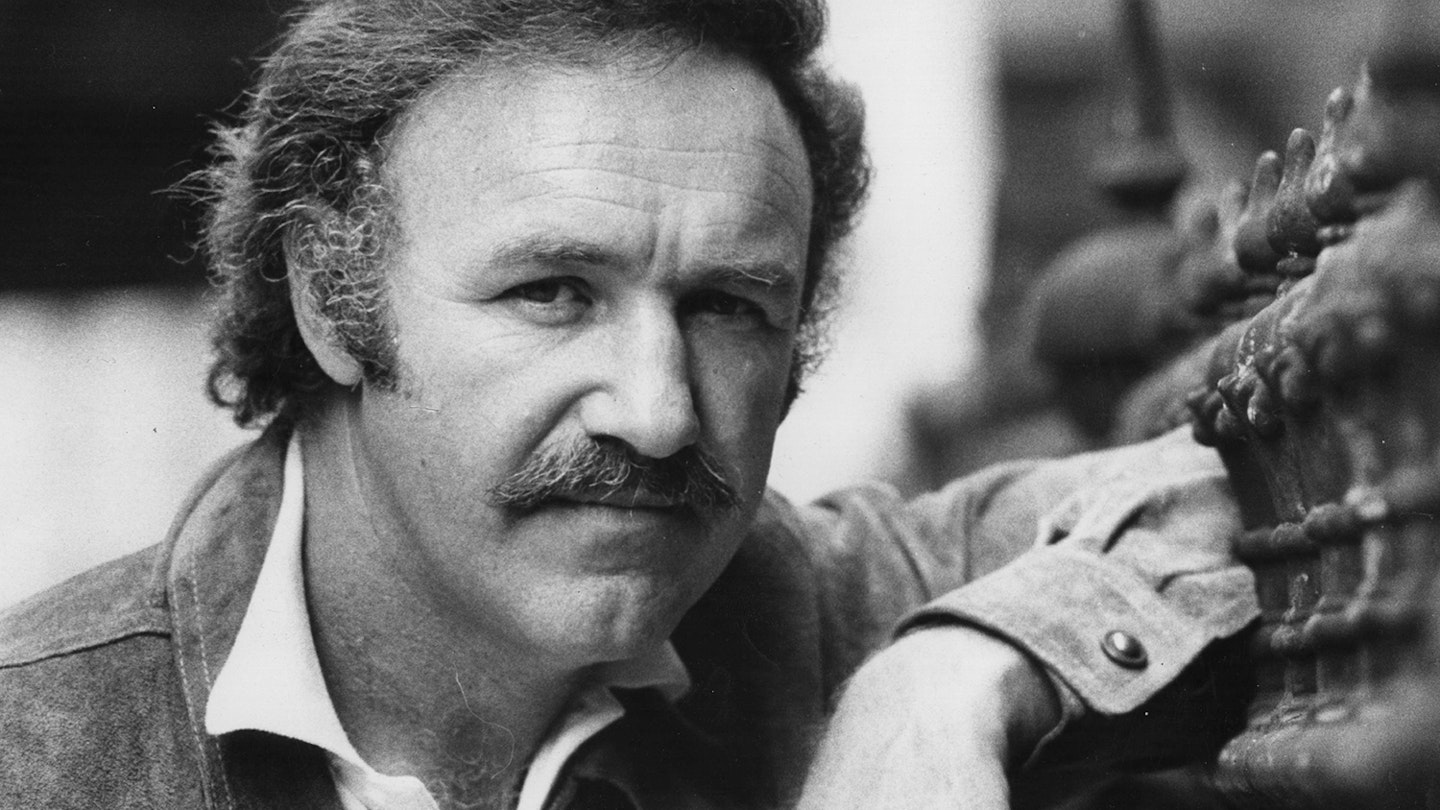

What distinguishes Bonnie And Clyde from the later slew of movies celebrating non-conformity — Easy Rider et al — is that alongside the life-affirming thrill they get from thumbing their noses at the law, both Bonnie and Clyde know that ultimately their fate is to die a violent death. This certainty haunts the film, and the moments where it bursts in on the gang's devil-may-care attitude are painful and sad. In one high-spirited sequence the outlaws have some fun by taking the nervy Eugene Grizzard (Gene Wilder in his first big screen role) for a ride. The scene is hilarious, with Wilder in top near-hysteria form, but it turns instantly dark when Bonnie learns that he is an undertaker and they kick him out of the car. Another beautifully-shot, achingly melancholy set piece is the one in which Bonnie, now a celebrity outlaw, goes home to visit her mother. With the light diffused by the swirling dust bowl, she talks about marrying Clyde and settling down close to her family. But she's fantasising about a future she knows she doesn't have. And her mother knows it too. "You live within a mile of me, honey, and you'll be dead," she says, and the flat, weary sadness in her voice is her daughter's death knell.

The point where time finally runs out for Bonnie and Clyde is one of the most shocking and memorable death scenes in the history of cinema. And the horrifically prolonged hail of bullets pummelling their bodies, which writhe obscenely long after the life has left them, is probably closer to the truth than anything else in the film. Overall it's a romanticised, revisionist picture, and even in the finale Penn can't resist ramming his point home with iconic slow motion. But in reality, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow were ambushed by police near Arcadia, Louisiana, in late May, 1934 and lawmen fired so many rounds into their car that Barrow's shirt was cut in half. Later, crowds paid to see their mutilated corpses in the morgue.

](https://www.mustard.co.uk/blog/hollywoods-leading-car-couples/hollywoods-leading-car-couples?auto=format&w=1440&q=80)

For better or worse, American cinema changed forever the day Bonnie And Clyde was released. Almost every aspect of it was revolutionary: the debt to the French New Wave (it was offered to Truffaut before Penn); the championing of the anti-hero; the free-wheeling camera work and cinematography; the use of unknown stage actors in supporting roles; and, of course, the painfully-rendered violence, all were enormously influential. Even Beatty's — some say grudging — agreement to portray Barrow as impotent was a brave move; for a romantic leading man of his stature to play a sexually dysfunctional character was absolutely unheard of. Critic Patrick Goldstein has called it "the first modern American film." Anyone remember what Bosley Crowther called it?