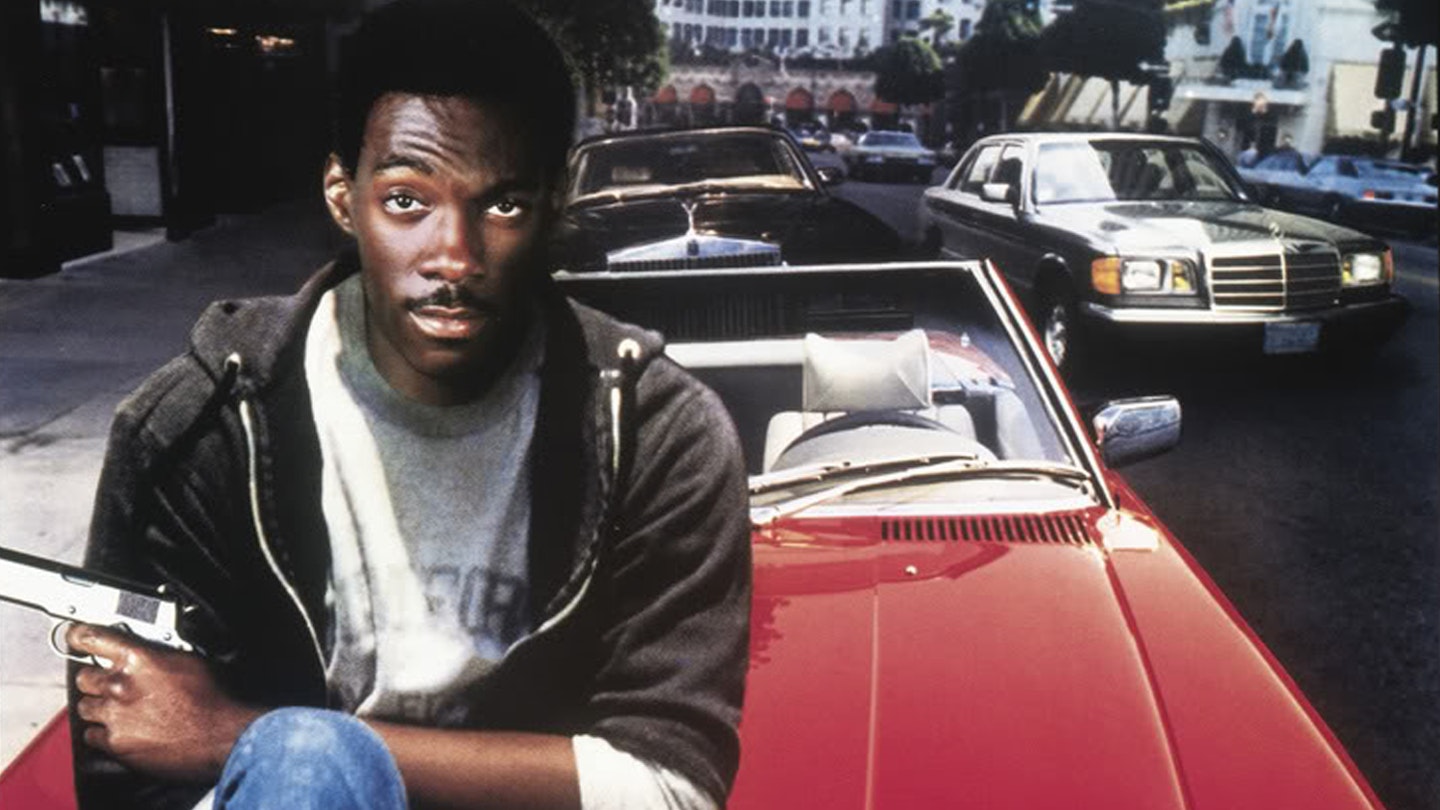

After Trading Places introduced the world to the rat-a-tat tongue and slacker cool of Eddie Murphy and 48 Hours had shown a tough, ethnic core, he hit upon the role that would turn him into a superstar — fast-talking, rule dodging cop Axel Foley. With a name like that how could it fail, especially as Daniel Petrie Jr.’s script was a terrifically deliberate reworking of the fish-out-water formula, peppered with prize one-liners and shaped by tidy plotting, and director Martin Brest gave it some real zip by blurring the divides between action and comedy. An idea that went on to define the ‘80s. It may be shallow and crassly commercial, but this is blunt-nosed entertainment of rare quality.

Brest’s smartest move was the casting of Murphy; everyone from Al Pacino to Sylvester Stallone had been circling the project, ready to play it dead straight. Once, Murphy’s ripe smile and easy tread were injected into what was a well oiled but standard policier, everything changed. The plot, involving Steven Berkoff’s pay-the-rent baddie’s drug ring, falls to the background, a sturdy framework for the star’s ribald energy.

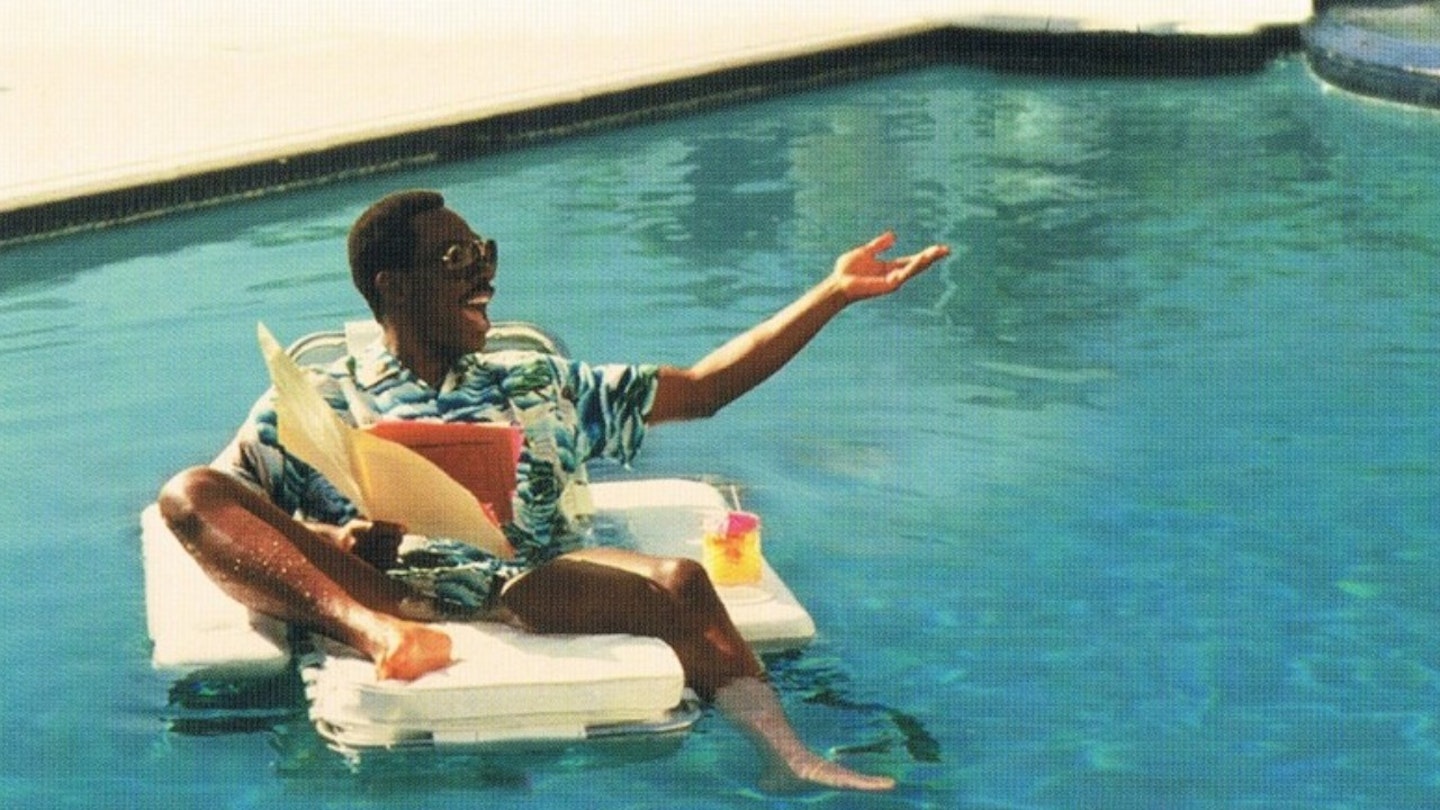

What matters here is Murphy bouncing his salty Detroit attitude off the empty-headed Beverly Hills platitudes, and his teasing, but quite touching, relationship with local cops Judge Reinhold and John Ashton, leaning the film into comedy. Poking holes in Hollywood’s housing estate is an evergreen opportunity, and Murphy gives it a real charge.

That said, there’s little effort given to human cost, the violence is carried off with a typically brute indifference. There’s not much here to believe in, rather than simply soak up, the embodiment of an era’s devotion to high concept. Harold Faltermeyer’s beeping synth riff “Axel F” reminding you exactly where the movie came from.