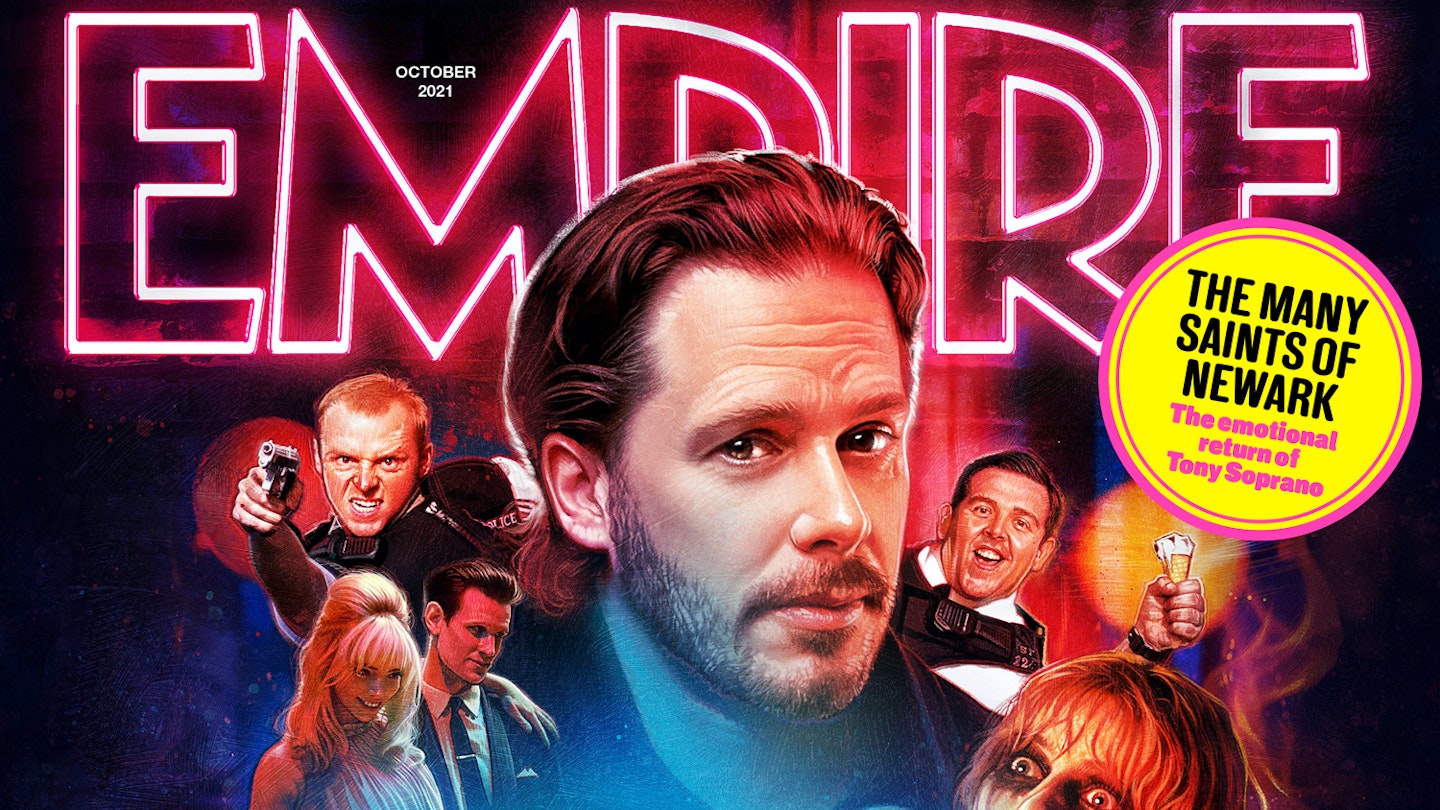

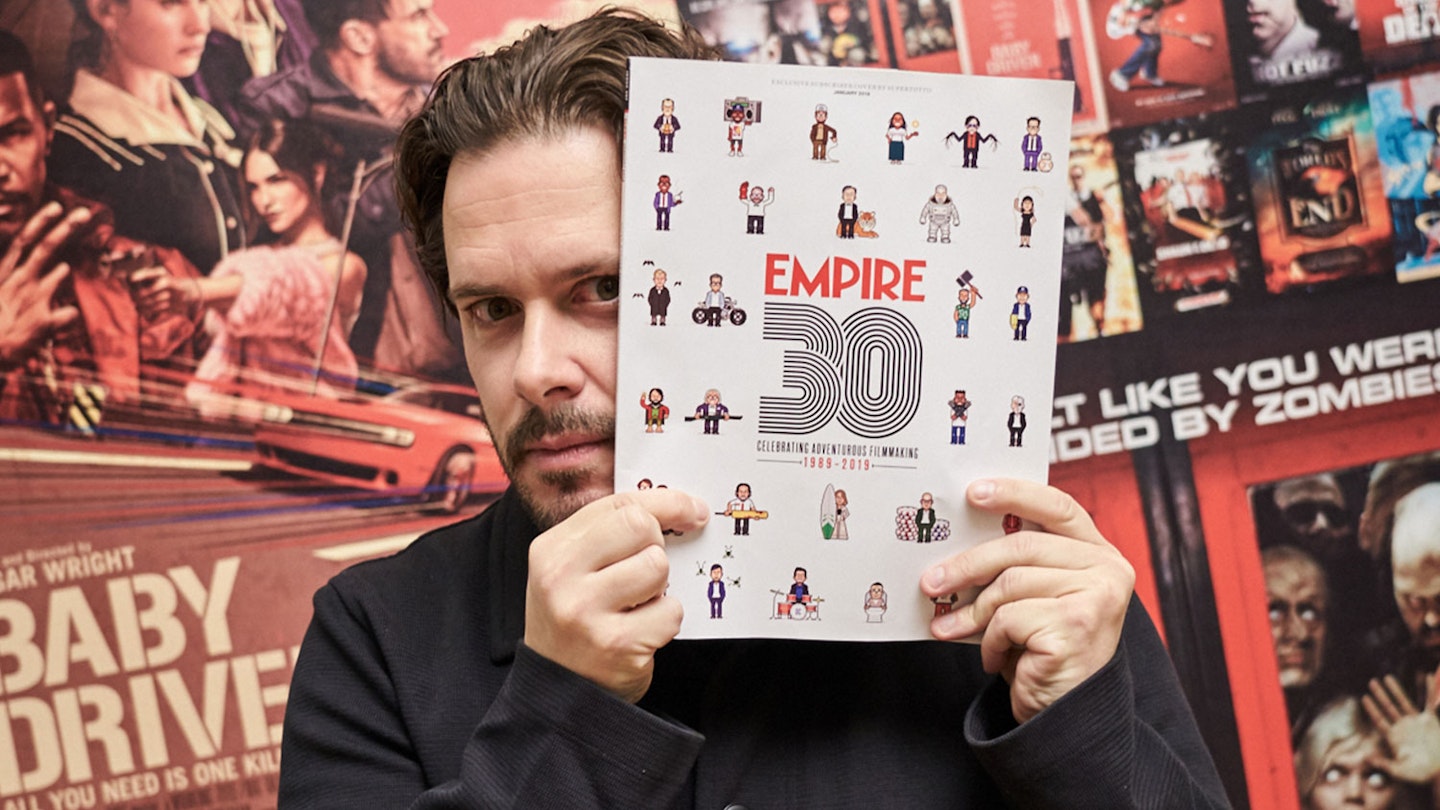

Twenty-two years ago, while sitting in the bedroom of his North London flat, writer-director Edgar Wright had a lightning bolt of an idea. Listening to The Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, and specifically all five minutes and 18 seconds of their song Bellbottoms, he had a thought: this would make an amazing car-chase song. Actually, a car-chase song

played into the ears of a getaway driver who can’t drive without music.

Watch the trailer below

It hummed under Wright’s feet for two decades, before becoming his fifth film and his first solo outing as writer and director. It became Baby Driver; one of the most utterly original films in years.

One of the most utterly original films in years.

The extraordinary thing about Baby Driver is evidenced in the first minutes of the remarkable opening sequence. As Bellbottoms kicks in and Baby (Elgort) launches into an exquisitely choreographed, full-throttle car chase set-piece, it becomes apparent that this is not a film just set to music. But a film meticulously, ambitiously laid over the bones of carefully chosen tracks. It’s as close to a car-chase opera as you’ll ever see on screen.

Baby is the man who marries the narrative to the beats — the young getaway driver who has worked for Atlanta crime boss Doc (Spacey) ever since he could see over the top of the steering wheel, paying off an old debt job by job. Baby’s an awkward fit in Doc’s heist crews (“Is he mental?” asks Jon Bernthal’s Griff), managing incredible feats behind the wheel, but always with earbuds in, blasting whichever songs he needs. At home, he cares for his deaf ‘Pops’ and makes mixes from secret recordings of gang members. Nestled in the centre of his tape collection is one labelled ‘Mom’ and there, on the yellowing paper, lies the heart of Baby’s story — the loss of his mother.

Baby finally sees a future beyond this life when he meets someone who’s as real to him as his mother was — waitress Deborah, who walks onto screen, and into his life, singing B-A-B-Y by Carla Thomas. In addition to music, they share the same thirsty desire to get the hell out of there — a plan derailed when Doc demands another job (“I said we were straight, but did you think we were done?”).

The only real flaw — and let’s deal with that right away — lies with the almost-Lynchian Deborah. She is the perfect outlet for Baby’s unspoken desires, but often has little agency

of her own. There are tantalising glimpses of a backstory — empathising with Baby on being a carer — but the details are unspoken, the chance to add depth to her character lost. Poignantly, during a discussion of songs that share her name, she says, “It’s not really about me,” and then later to Baby, “Every song is about you.” As they sit in the diner his mum worked in, the iPod she bought in his palm, you sense that this isn’t entirely about her either.

That said, the supporting cast of characters is one of the film’s biggest strengths. Spacey’s Doc is full of menace, yet oddly paternal and gifted with some of the best one-liners (“He puts the Asian in home invasion,” he says of one crew member). Partners in crime Buddy and Darling are played by Jon Hamm and Eiza González to just the right side of clichéd comedic perfection: she’s all acrylic nails and gold hoop earrings; blowing pink bubbles while breathlessly urging Buddy to kill for her. Buddy’s an ex-Wall Street guy who ran off with his favourite stripper. They lightly kick the story along with a piece of exposition here and a moment of levity there, with Hamm turning in a third-act performance that is so wonderfully deranged you feel Don Draper spinning in the earth below his feet. Jamie Foxx rounds it out as hard-nosed, nihilistic career thief Bats.

And what of Baby? In the wrong hands, an accidental criminal with a dead mum, a hearing problem and a good two-step could have been drawn clumsily. Between Wright’s fingers, he’s charming and beautifully vulnerable. You know in your belly that this is no life for him, knots forming as Doc says of this one last job: “So what’s it going to be? Behind the wheel?

Or in a wheelchair?” And so kicks off the glorious final hour — a high-octane, tightly choreographed eye-orgy of violence, action, drama and, yes, love. A heady, intoxicating combination that Wright manages to get just right.