You know the book. If you use public transport, you’ll recognise it as the one everyone was reading circa 2004. There was that Booker Prize shortlisting, the reams of laudatory articles about its author, Ian McEwan. And now arrives the inevitable film adaptation, which should by rights be as stilted and anaemic an affair as most big-screen versions of ‘serious’ fiction, a (Merchant) ivory tower of self-important emoting from RSC heavyweights. Except that this quality-drenched effort is as stilted as a bellydancer.

Where did it all go right? All the hallmarks of the Remains Of The Day school of longing glances, class conflict and stiff-upper-lippery are there. The scene is set in a country house on a hot summer’s day in 1935 (so very A Room With A View) as a little girl plans a play, with her reluctant cousins starring.

This is Briony (Saoirse Ronan), aspiring writer and priggish know-it-all. Cosseted by her family, her life experience wouldn’t fill a thimble- but her lack of self-awareness, as she teeters on the brink of adolescence and its attendant hormonal storms, makes her shockingly dangerous.

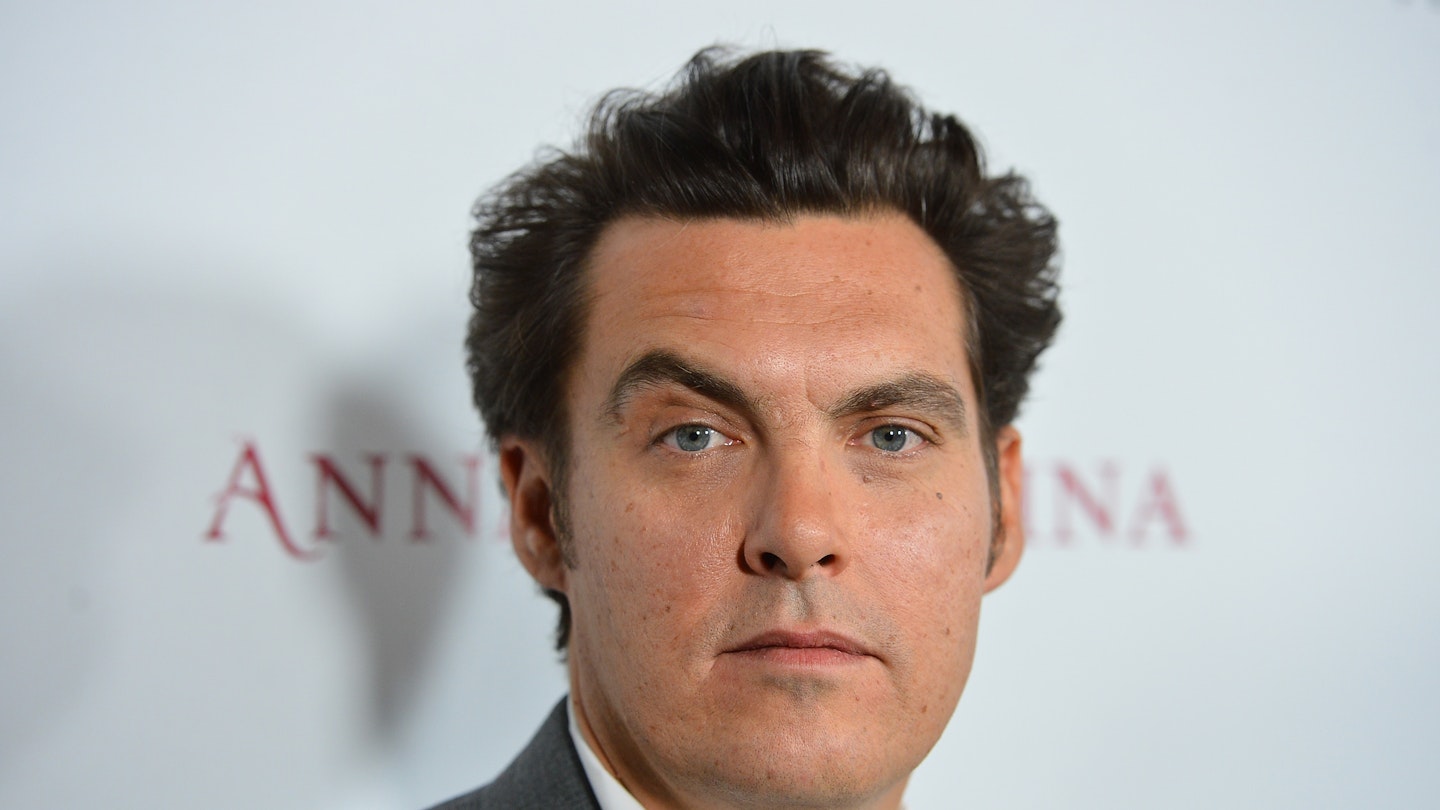

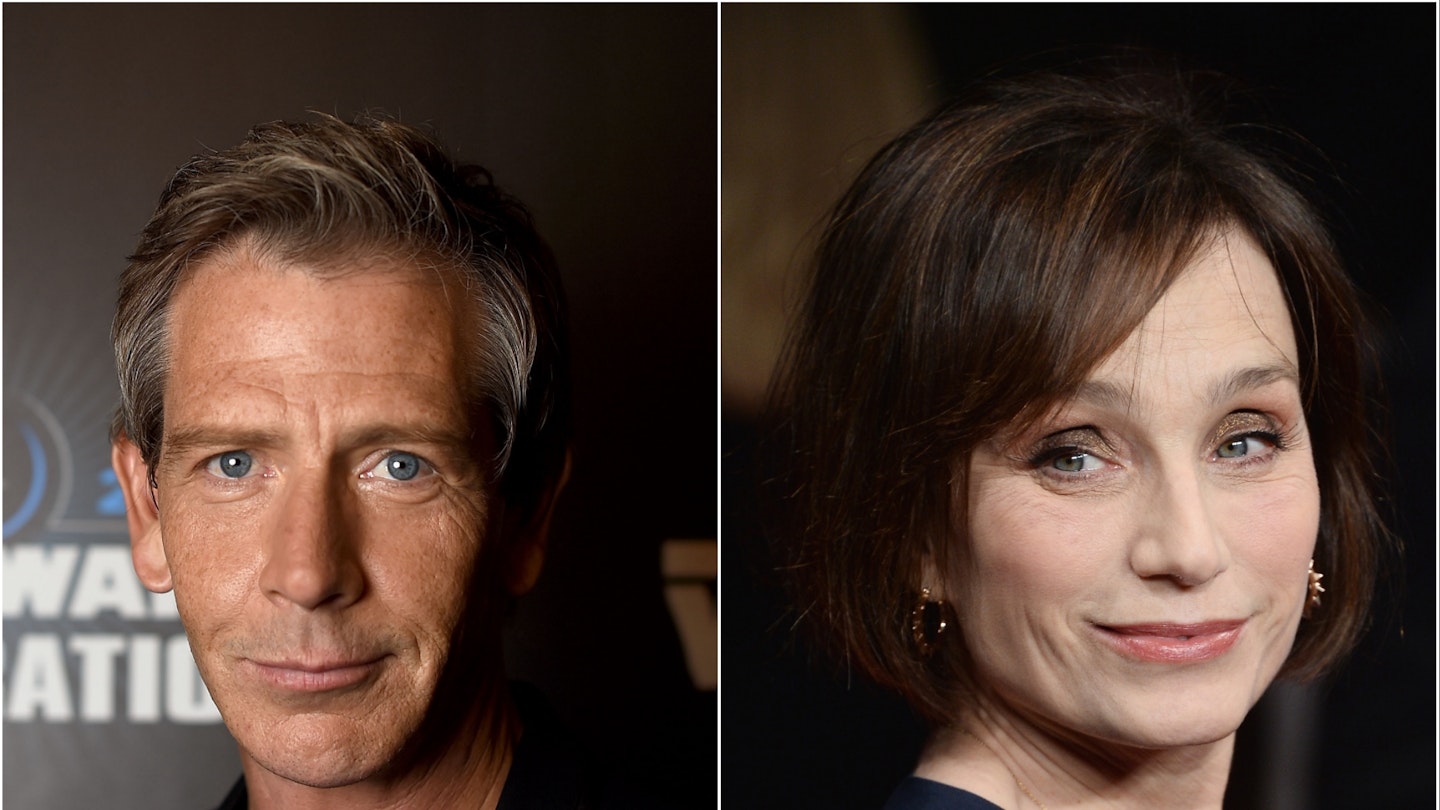

Meanwhile her sister, Cecilia (Keira Knightley), lounges by the pool with brother Leon (Patrick Kennedy) and his friend Paul Marshall (Benedict Cumberbatch, effectively making the skin crawl), keeping her distance from social upstart Robbie (James McAvoy), a scholarship boy with little to recommend him but himself.

There’s a careful contrast between the gilded youth of Cecilia and friends, literally glowing in Seamus McGarvey’s burnished cinematography, Robbie’s earthier colours and Briony’s cold little face, pinched with self-importance, all setting up a conflict to come.But it’s the tone that sets this apart from more traditional, ever-so-slightly-fusty inter-War dramas. Mature actors barely get a look in - near-cameos from Brenda Blethyn, Gina McKee and Vanessa Redgrave aside, no-one over the age of 30 even registers.

Magical-realist underwater scenes make the stately home seem an idyll, but the oppressive heat that radiates from the screen hints at tension, sexual and otherwise, bubbling under the surface. The most erotic sex scene in years - this despite the fact that both parties remain almost fully dressed - can’t ease the growing dread. Even aside from the World War glowering on the horizon, it’s clear that something is about to go horribly wrong.

To say much more about the details, however, would be to risk unbalancing a plot as delicately calibrated as clockwork. If you’ve read the book, you know what’s coming. If you haven’t, count yourself lucky, and watch with your heart in your mouth as events build to a climax barely halfway through.

Still, it’s not giving much away to say that we see the central three characters - Cecilia, Robbie and Briony (now played by Romola Garai) - again in 1940, as World War II rages around them. Cecilia and Briony are working as nurses in London, while Robbie is part of the ill-fated British Expeditionary Force, trying desperately to reach the evacuation point at Dunkirk in the darkest days of Britain’s war effort.

Their golden youth has faded to something colder, a world that’s watercoloured rather than lit from within. The blue-tinged French countryside through which Robbie and his comrades tramp is already war-weary, while in London nurses march in military formation, colours still undimmed and heads unbowed. They face the same rude awakening that the soldiers have already experienced, but there’s a neat parallel between military and medical roles - everyone faces the harshest realities of war, but the worst, for our three principals, is perhaps already behind them.

It’s in this second half that director Joe Wright really fulfils the promise of 2005’s Pride & Prejudice. That was unanticipated before release, overshadowed by a still-loved BBC adaptation, but demonstrated a sure feel for character and nuance from its debutant director.

Here, he displays storytelling and technical flair to match his ability with actors. The opening half of Atonement may feel dreamy, but barely wastes a second in building to its shocking conclusion. The second half, although packed with incident, is less pacy, the middle section deliberately slowing to compensate for the novel’s lack of a second act (Briony turns from self-righteous to stricken in the turn of a page). We have the chance to wallow in the mess she has left, and realise the full extent of the crime for which she must atone.

But that’s not what’s going to make Wright’s reputation. In one near-wordless, five-minute tracking shot on the beach at Dunkirk, as Robbie’s exhausted troopers stagger in to find not refuge but chaos, Wright stakes a claim to scene of the year. Vignettes - cavalrymen shooting horses to deny the advancing Germans, drunks draining the local bars - form a meticulous picture of the desperate straits of the Allies. Amid the booming artillery, scattered shipwrecks and soldiers searching for food and refuge, Wright keeps turning back to McAvoy’s face, as the best young British actor of our times reflects the weary horror of the day before the ships arrive. The sheer logistics of the shot are impressive, but it’s the emotion that makes this such an astonishing achievement. This is as effective a World War II beach scene as Saving Private Ryan’s opening, a fight for survival of a different kind.

But if McAvoy impresses once again, it’s Knightley who finally stakes her claim in a grown-up part. Those cut-glass tones are exactly posh enough to fit Cecilia, a more brittle role than the feisty grrrrls she’s played before and one more suited to her delicate beauty. She might want to specify that Wright direct every film she makes in the future.

Romola Garai gets the more difficult role, a character who lives an almost entirely internal life. She does a fine job, but frankly she’s eclipsed by Saoirse Ronan as her 13 year-old self.

Such is the quality of the production as a whole that any flaws in the narrative are almost immediately eclipsed by the next accomplished scene. There are contradictions, questions left unanswered. When does Briony realise her mistake? Does she truly believe that atonement is possible, that she can regain some measure of grace? And do we agree? Perhaps, in the end, merely to pose such questions is the point, a measure of the film’s intelligence and its emotional power.

.jpg?ar=16%3A9&fit=crop&crop=top&auto=format&w=1440&q=80)