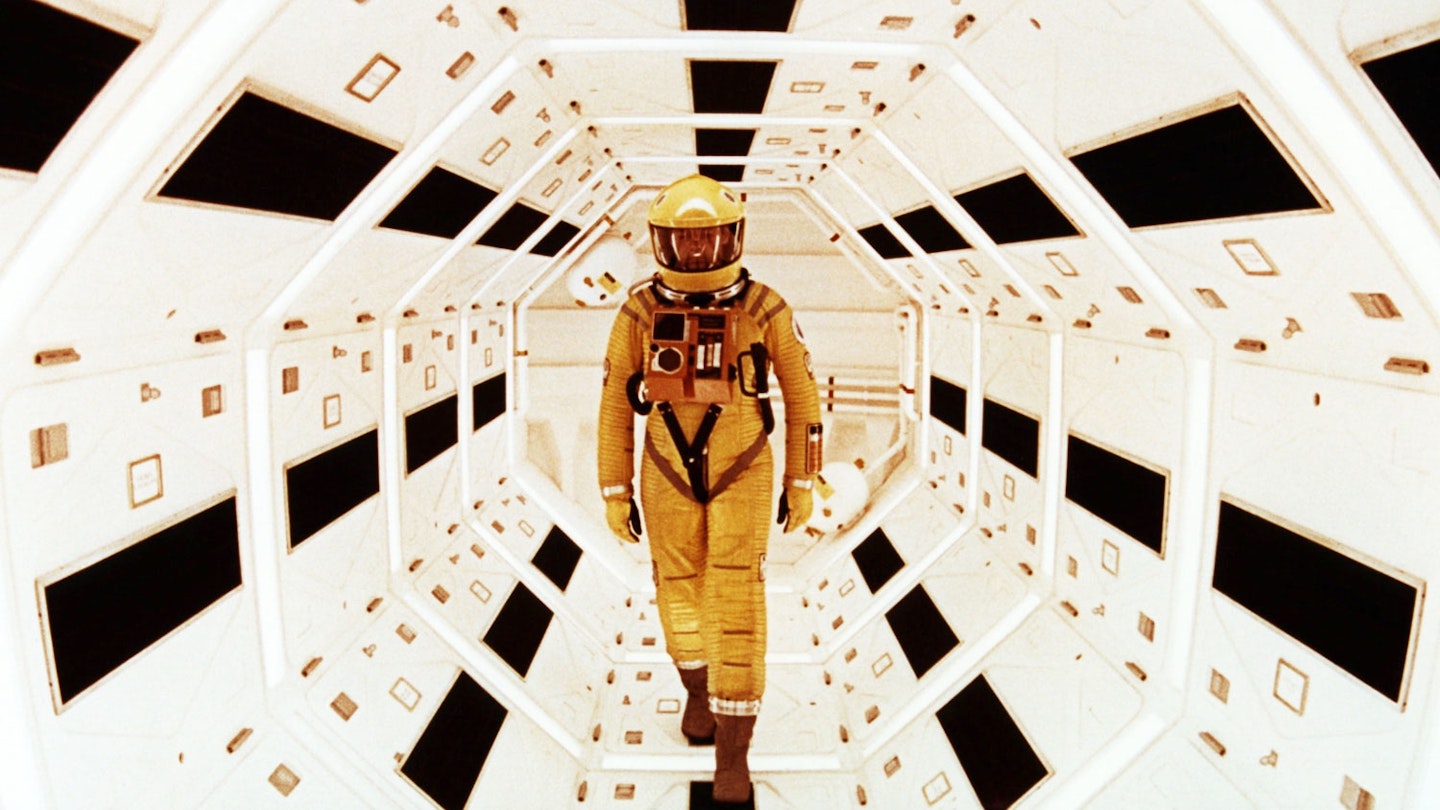

Whatever the backstory, that Stanley Kubrick implored Spielberg to make his long-cherished, existential sci-fi epic, or Spielberg hitched a lift on the late master's heritage, it doesn't matter. Sure, the film is loaded with Kubrickian touches (it commences with a cold, eloquent style, it refuses to be rushed, it's brimming with enormous, philosophical debate, its ending is potty), but this is the work of a living, breathing master - and, boy, is he good. Taking Kubrick's nurtured sapling, Spielberg adds love, ILM miracle-grow and a fierce intellect so often overlooked (he scripted, remember), unfurling his imagination on a dazzling blend of Pinocchio, Blade Runner, 2001 and a whole lot more besides.

Big time sci-fi from a (not really) child's POV it may be, but forget a comforting E.T.-like fable. The film seethes with an edgy coldness that must have been born in the Kubrick vaults. Opening up with a familial drama, there is the nascent creepiness of a horror movie, as forlorn couple Monica and Henry (Sam Robards) are selected to take on David, a "mecha" (robot) child capable of love. But once you encode the love circuits there's no going back.

Naturally, Monica is freaked out, but her instincts to love take hold, even as she dares the irreversible.

These are weighty questions, indeed: What does it mean to be real? What does it mean to love? Does the power to love make us real? What is the price of loving? Gulp.

Osment is staggering. In a mesmerisingly-controlled performance he creates a perfect balance between charm and otherworldliness, defying but imploring the watcher to empathise. This is a mighty old talent for one so young. Following a traumatic sequence between "mother" and "child", the film shifts gear as David journeys to the "real" world. Accompanied by a groovy talking teddy bear, he pals up with sex-mecha Joe, escapes from a Flesh Fair (where humans gleefully exterminate mechas - very Schindleresque) and ventures to the noirish Oz of Rouge City.

Time to mention the CGI. A.I. is the finest example to date of the application of computer graphics to a storyline. In the ramshackle mechas of the Flesh Fair there are seamless half-faces, eyeless holes, actors' faces that split open to reveal their inner workings. Better still is the creation of a schizo near-future, equally antiseptic utopia and sleazy dystopia: Rouge City is Las Vegas gone mad, a neon-soaked dreamscape that beggars belief. David's quest concludes in the near-submerged Manhattan, a flawless vision of a drowned metropolis. There's half an argument to sit back and let the sheer beauty of the film wash over you. But it has somewhere else to take you, entirely. To the "ending".

Perplexing, infuriating, mind-blowing: it's a voyage into a wonderland where the fairy tale motif becomes inseparable from the cool future-vision. You've got to admire Spielberg's daring - ditching the intellectual backbone for a spiritual send-off - but it doesn't sit easy. Some people might reject that wholesale; the majority might balk at the overlong and "out there" ending. Perhaps that is the point. A.I. will have you debating until the landlord threatens to call the police. It's that kind of movie. Thank God for that.