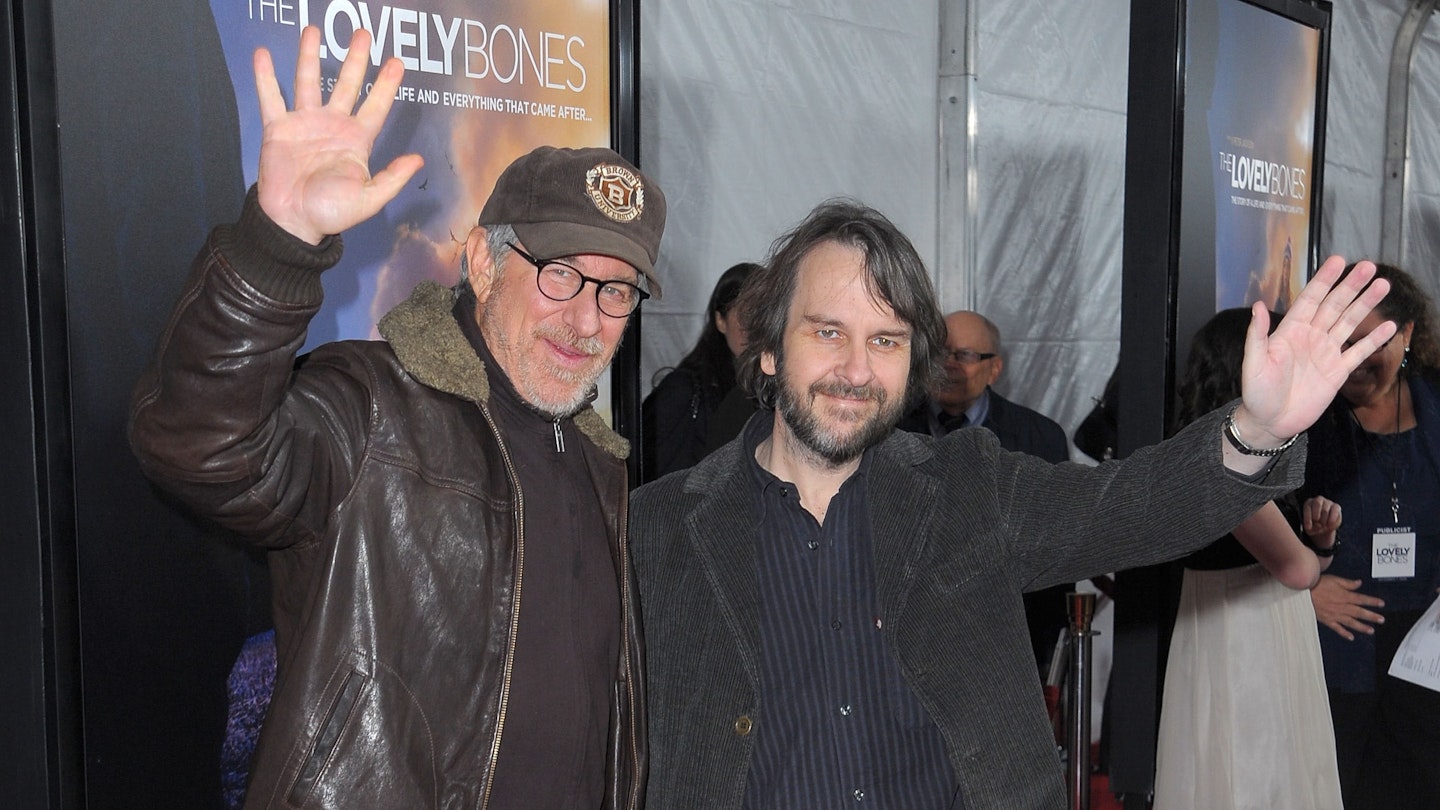

High-minded types, usually French, sometimes Belgian, contend that all art is finally self-portrait. This being the case, maybe we can catch a reflection of the animated double-act that is Tintin – globetrotting journalist of indeterminate age but with last-ditch gumption in spades – and Captain Archibald Haddock – semi-functioning, disaster-prone alcoholic salt of (nearly) unfailing positivity – in the budding partnership of Steven Spielberg (our Tintin) and producer Peter Jackson (our Haddock).

Heaven forfend we suggest The Hobbit director conceals jars of whiskey about his person or that his liquor-fumed belches might kick-start the engine of a crash-landing aircraft, but the Kiwi producer has cajoled a joie de cinema from his American director, who appeared so bogged down upholding the legacy of The Kingdom Of The Crystal Skull. Animated or not, depending on your stance of this whole performance-capture game, Spielberg has brought a boy’s heart, an artist’s guile, and a movie-lover’s wit to computer generating Hergé’s immortal hero. Where Jackson was the Tintin geek, following the ageless Belgique Morrissey on his dashing but non-superheroic escapades as a kid, Spielberg only got the bug when a French critic (them again) likened Raiders to Europe’s all-time favourite comic-book idol. In effect, Spielberg landed the goofball sidekick with whom to traverse the globe, without leaving the studio.

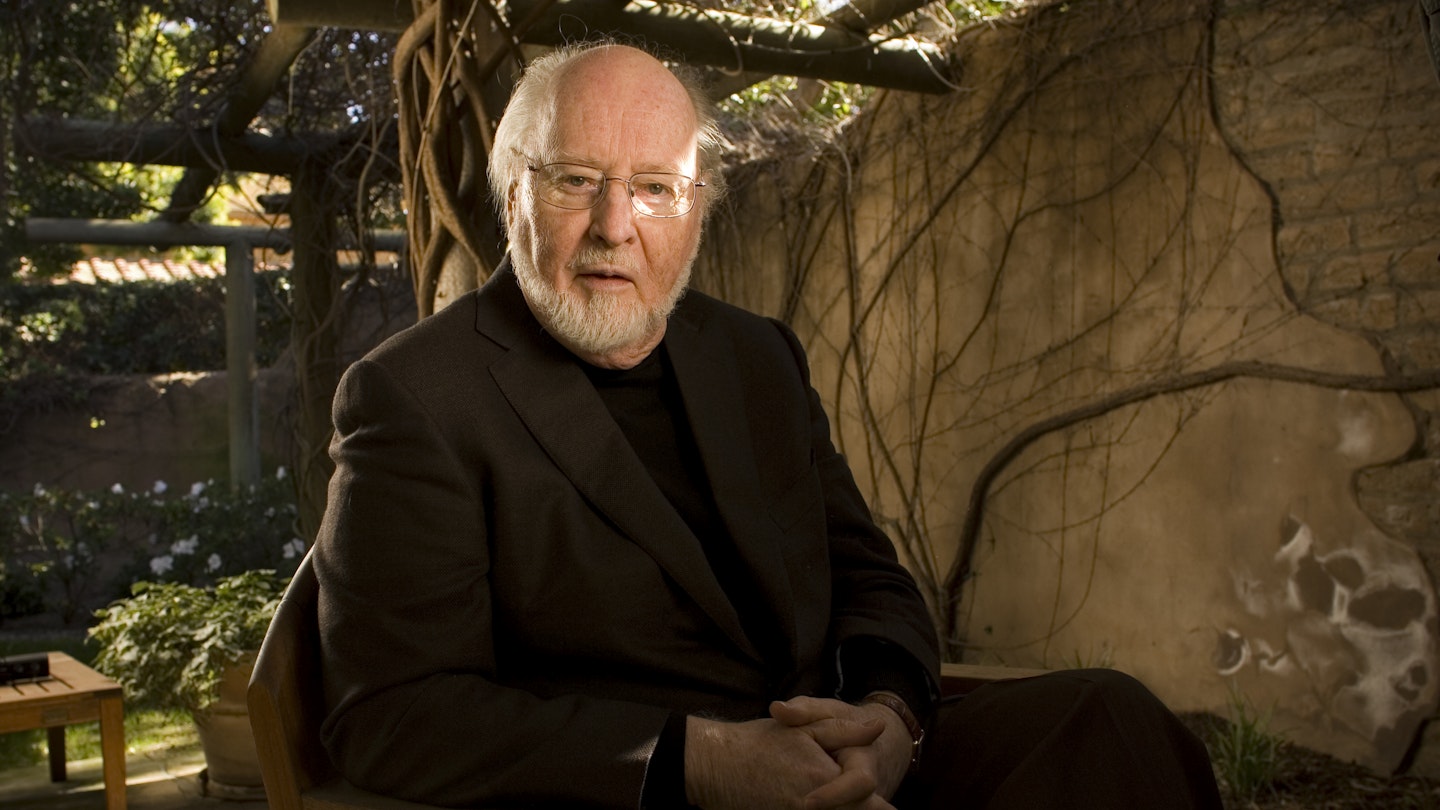

From the Nouvelle Vague flourish of the opening credits, featuring Tintin in silhouette dashing past giant typewriters and former foes, recalling the Saul Bass-themed curtain raiser of Catch Me If You Can, set off by John Williams’ fleet-fingered piano score, the mood is set. Here is a joyful play of opposites: the romance of old-school cinema, conjured by the slick synthesis of CG wizardry.

Vitally, as near as can be, here too is the ardent, moules-frites aroma of Hergé’s rainbow-lovely world of high adventure and colloquial antics. Spielberg’s first venture into animation (we’ll stick with that) expands the Belgian’s formal elegance into a wonderland of digital detail without ever losing sight of the bubbly charm of the books. Encompassing the shovel chins and bobbled noses of the Hergéian caricatures, Weta pursues a whimsical variation on photoreal. But it’s not just about the flour-fine textures of sand or gunpowder, the flicker of firelight across a blade or a breeze ruffling Tintin’s unbendable forelock. This is also an expansion of the Spielbergian dream (with a tincture of Jackson’s boldness). Like a boy set free from the schoolroom of reality, he lets fly.

In an exalted midsection, in which Haddock, stricken by sobriety, relays his family history, we flow with unceasing movement between his telling and a titanic sea battle of old. Here, finally, is what the medium offers a filmmaker. Spielberg reaches a delirium of creativity through match cuts and dissolves: reflections in blades, bubbles, the bottom of a whiskey bottle transformed into a telescope, and a desert morphing into a squalling ocean. Across the film’s sunburst of entertainment, the director applies the rain-slicked atmosphere of Jules Dassin’s noir, Indy’s self-mocking awareness of genre, and the catapult-momentum of the Keystone Kops. The 3D, neither fish nor fowl, is simply part of whole immersive effect: Hergé by Spielberg.

We open in what might be Paris, in what might be the ’30s – as with Hergé, it is a mythical, timeless world: cobbled streets, shuttered windows, old ladies walking decadent dogs, and for the eagle-eyed cineaste a homage to Robert Bresson’s 1959 Franco-classic Pickpocket. The introduction of Tintin is a gag so good we can’t possibly spoil it here. There has been an understandable fretting over how Tintin would be depicted on film, a tricky task given his Belgian creator effectively made him a blank slate on which we project our dreams. Spielberg, with his writing trio of Anglo-nerds – Doctor Who’s Steven Moffat, Scott Pilgrim’s Edgar Wright and Adam & Joe’s Joe Cornish – has bravely kept faith with the author.

Jamie Bell gives him a neutral English accent and a boyish gait, but he remains lightly sketched: depending on the age of the viewer, translatable to 15 or 30. His face is blankly handsome, cheeks lightly blushed, eyes expressive and bright as light bulbs (not a hint of the dead-eye that plagued Robert Zemeckis). It is the jutting crest of hair that cuts a shadow as iconic as the brim of Indiana Jones’ fedora.

As we know Indy as an easily diverted archaeologist, Tintin’s job description is cleared up – he is the roving reporter who never files his copy! Although, as Harry Thompson reported in his excellent biography Hergé & His Creation, the writer-artist was drawing upon the ’20s fashion for adventurer-reporters, who created their own news. And this boy certainly has a nose for a story: he barely strolls through a French market, before he’s up to his jodhpurs in a conspiracy surrounding the Haddocks’ absconded heritage and Sakharine (Daniel Craig) of the perfectly Mephistophelean beard.

While Tintin is coolly abstract, his co-stars are a gang of Dickensian cranks and kooks. The potential mishap of Snowy, his faithful wire fox terrier, is rendered as the smartest dog in town regularly tugging his master from the brink of disaster, but not some preternatural Scooby-Doo. Although more fool those who leave a sandwich untended. In short, the kids will adore him. For all that the film plays the nostalgia card for the devoted Tintinologist (their hearts warmed by soprano Bianca Castafiore’s glass-shattering assault on Haddock’s eardrums) Snowy offers the unabashed charm of the heroic pooch.

Even the most Hergé-phobic will know that Haddock is the funny man, Tintin the straight guy. Andy Serkis, in a broad Scots brogue, again surpasses the limitations of not being physically there. The jury is still out on whether performance-capture attains something greater than animation, but Serkis gives the movie its rich, flawed, bountiful heart. In another bravura set-piece that amplifies like a wondrous Rube Goldberg contraption, Tintin picks his way between the swaying bunks of a cabin full of snoring Quints, as Haddock unhelpfully regales him with their distinctive traits. Reporting on the tragic loss of one particularly shifty crewman’s “eyelids”, we glimpse a pair of yawning lifeless(!) eyeballs. “That was one hell of a card game!” sighs Serkis with perfect timing, a faraway look momentarily in Haddock’s piercing blue eyes. For all the flurry of detail, the victory here, like Pixar, is of creating recognisable humanity.

Away from Haddock the script struggles to be out-and-out funny. Interpol’s worst, Thomson and Thompson, in the plumbed double-act of Pegg and Frost, provide slapstick and idiocy with a fifty per cent hit rate. The much funnier Professor Calculus remains on the back burner for a Peter Jackson-directed sequel.

No room is found for Hergé’s political satire, or his more becalmed, intuitive moments, to gaze, incredulous, at the world – an iconography so ingrained in the artist’s style it might be untranslatable. And, with performance capture, there is still that gravitational pull toward endless chase sequences. The pace throughout is rat-a-tat-tat quick, the plot tripping along, and the exposition breathless. You have a job keeping up, but never at the expense of the sheer goodwill. While luxuriating in its pre-existing universe, here is a film imploring you to join in. It would take a hard heart to resist.